In Appreciation — Gary Nolan

Years with Cincinnati: 1967-1977

There can be no In Appreciation series without Gary Nolan.

Gary Nolan is my all-time favorite pitcher.

He was fantastic. He was wonderful. He was tough. And he loved to pitch. And I loved watching him do it.

Nolan burst onto the scene in the spring of 1967, barely a year out of Oroville (CA) High School. He was brought to Reds’ spring training for a look after he went 12-6/2.10 in rookie ball. He struck out 229 and gave up only 129 hits and 55 walks in 176 innings.

“I believe I can make this team,” Nolan said.

“I was waiting for him to pitch himself off the team,” said manager Dave Bristol. “Instead, he kept throwing the ball over the plate and getting people out.”

And make the team he did, marking his April 15 debut by striking out the side in the first inning of a 7-3 win over Houston.

The signature moment of his rookie season came June 7 against the Giants, when he struck out Willie Mays four times consecutively – “the first time that has ever happened to me,” Mays said. This led to some friendly byplay the following day, as Mays called out to Nolan:

“Hey, Nolan! Gary Nolan!”

Nolan turned around.

“I’m Willie Mays!”

“I know who you are, Willie.”

“I didn’t know you yesterday. But now I know who you are, too,” Mays said to general laughter.

Nolan actually struck Mays out the first five times they faced each other. But he reminded me that “Willie got even later on. He got a few home runs off me,” Nolan said, laughing.

A friendship born of mutual respect began that day in 1967, and Nolan and Mays are still great friends. They visit whenever Nolan comes to AT&T Park. When they see each other, Mays says, “Gary Nolan. Gary Nolan!” and shakes his head, laughing at the memory.

Nolan finished 14-8 in that 1967 season and was third in Rookie of the Year voting, behind Tom Seaver and the Cardinals’ Dick Hughes.

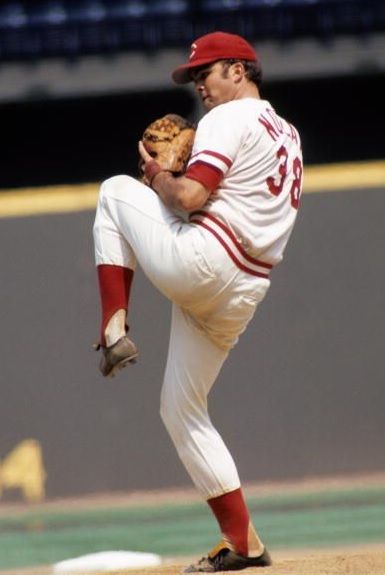

I was able to watch Nolan pitch on TV a couple of times in 1967, and was immediately captivated by the blazing fastball, great control, and his motion. He was beautiful to watch, though some pitching coaches warned that his “tight” delivery would lead to arm problems.

And in spring training before the 1968 season, Nolan felt shoulder tightness before a game against the Red Sox.

“I was very frightened at what happened,” Nolan said. “The doctors could find nothing seriously wrong.”

“We may send him to the minors to get in shape,” said general manager Bob Howsam. No mention or acknowledgment of the shoulder pain Gary was suffering.

Nolan was left behind in Florida when the Reds broke camp to start the season. The pain continued, at one point being so intense that Nolan dropped to his hands and knees on the mound.

Nolan was recalled to Cincinnati and began working with pitching coach Mel Harder. He was added to the active roster in late May and went 9-4 while leading the team in ERA.

In 1969, Harvey Haddix was the Reds’ pitching coach. He was one of those who had predicted arm trouble for Nolan, and they spent much of spring training refining Gary’s motion to be more fluid and synchronized.

Opening Day 1969 was a classic, typical Nolan start. I was there at Crosley Field as Nolan struck out 12 Dodgers. And the Reds lost 3-2, with Don Drysdale getting the victory despite allowing back-to-back home runs in the first inning.

The problems continued in Nolan’s next start against Atlanta. He pulled a muscle in his forearm pitching to Hank Aaron. He was sent to the minors for a time, then recalled to go 8-8.

In 1970 Nolan was 18-7 in the regular season, but the career-long problem – lack of run support – showed itself in the playoffs against Pittsburgh. Nolan pitched a nine-inning shutout, but the Big Red Machine was also shut out, and only a tenth-inning rally got Nolan a victory.

After a 12-15 season in 1971, when he was developing a changeup (a palm ball, he told me), Nolan came out blazing in 1972, going 13-2 to start the season. Then he felt a “pop” in his shoulder and was limited a great deal the second half of the season, finishing 15-5 with a 1.99 ERA.

All sorts of bizarre treatments were tried in an effort to ease the pain in Nolan’s shoulder: an electrified needle to kill a nerve that was thought to be the problem; a visit to a dentist to remove an abscessed tooth (seriously).

Nothing worked.

The 1973 season was a disaster for Nolan, as the shoulder problems persisted. He made only two starts for the Reds, pitching a total of 10 innings. Again, the doubters fired their verbal shots. Again, no diagnosis worked to cure his shoulder problems.

“The hardest part was that some people – even some of my teammates – really didn’t think there was anything wrong with me. They said it was all in my head,” Nolan recalled. He once told Pete Rose, “Pete, I’ve been dead for a year-and-a-half, and they haven’t even given me a funeral.”

“Pitchers have to throw with pain,” manager Sparky Anderson told him. “Bob Gibson says every pitch he’s ever thrown cut him like a knife. You gotta pitch with pain, kid.”

In spring training 1974, Nolan acted on his own to arrange an appointment to see Dr. Frank Jobe in Los Angeles. X-rays of his shoulder, taken at a different angle than any others, showed a ¾-inch needle-like bone spur.

“Gary Nolan had to have a very high threshold of pain to pitch at all with that in his shoulder,” Jobe noted.

Surgery was performed in May, and by July, Nolan was on a throwing program at AAA Indianapolis. In 1975, comeback complete and doubters silenced, Gary won 15 games. And in 1976 he won 15 more, and Game 4 of the Reds’ sweep of the Yankees in the World Series.

In 1977, his troublesome shoulder finally gave out for good – a rotator-cuff injury, he told me — and after a midseason trade to the Angels and a few ineffective appearances for that club, Gary Nolan retired.

He was elected to the Reds Hall of Fame in 1983.

For many years, Nolan rightfully held a great deal of bitterness toward the Cincinnati organization. He did not attend reunions or other team functions, and he lived in Las Vegas as a card dealer and executive host.

But with the Reds under different ownership and administration than during his playing years, and following a chance visit to the Reds Hall of Fame, Nolan’s bitterness was lessened. He now makes periodic trips back to the Queen City, and he is an active participant in Reds activities.

He now feels appreciated again, as he should be.

Joe Posnanski notes:

“The extraordinary thing is how Gary Nolan looks back — not at the career-saving surgery itself, but at something entirely different. He looks back and sees the kindness of Frank Jobe.”

I have never been all that big on autographs – especially for a price. I realize they can be a valuable way for ex-players to make some needed cash. But I felt it was a process that should be done willingly and have some meaning – not as an investment for the buyer or a “job” for the player. I have a few signed items, and they are treasured for reasons other than just the signature. I swore I would never pay for an autograph.

That changed in 2017 when Gary Nolan came to Cincinnati for a signing.

I had the good fortune to purchase a game-worn jersey of Gary’s for my man cave, and I realized if there was one player who deserved to make a few bucks this way, it was he. And for all the thrills he gave me and all the great games he pitched in pain, the autograph fee was a drop in the bucket.

I’ve been around enough players that I rarely get star-struck anymore; but I was shaking as I approached the signing table. I introduced myself and thanked him for all that he did. He could not have been more pleasant and down-to-earth. We had a brief chat, and talked again later that day at a Q&A. He was so kind to all of us, and he was pleasant and patient with our sometimes-inane questions.

The jersey Gary signed for me hangs proudly in the Big Red Machine section of my personal “Hall of Fame” in my man cave. There are probably 30 framed jerseys there.

Only one player is represented twice: #38, Gary Nolan. Reds home and road.

road.

It’s so rare these days that perception and reality about a person come together as one. Well, it happened that day.

Thank you, Gary – for everything you gave to all of us who were privileged to follow your career.