Jim Maloney and I had such a wonderful conversation that I have split it into two articles. Part 1 covers his playing career as a fabulous pitcher for the Reds in the 1960s; Part 2 [here] is about his life after baseball.

Part 1 covers his playing career as a fabulous pitcher for the Reds in the 1960s; Part 2 [here] is about his life after baseball.

EARLY DAYS IN FRESNO

You had quite the baseball team in high school — and you weren’t even a pitcher yet.

There were several guys who went to the big leagues from our Fresno High team: Pat Corrales — who is still in baseball in the Dodgers’ front office – he was our catcher. Dick Ellsworth pitched 10-11 years in the big leagues [primarily] with the Cubs; Dick Selma was a reliever with the Cubs for a while.

We had a coach named Ollie Bidwell, and the way you played the game was fundamentals – that’s all you worked on. And I was a shortstop in those days, so I knew how I knew how infielders would move when balls were hit around – to go take the cutoff throw or cover a base – the ball dictated where you moved. Don’t be throwing a rainbow in there: you gotta keep the throw down low, so the cutoff guy can field the ball, and keep the runner from going to another base.

You were the shortstop, and a .500 hitter your senior year?

Yeah, I could hit a little bit – it was high school. I’d get two strikes on me and choke up a little more on the bat – I was embarrassed to strike out. In those days, you didn’t strike out, or you tried not to. But don’t be swinging wild all three times up there.

That’s the way I learned to hit; I made contact. I had decent power – not major-league power, but I did hit seven home runs in the big leagues.

The first three or four years I was in the big leagues, Hutch [Reds manager Fred Hutchinson] used me as a pinch-hitter after the other guys were used. I’d be down the list, but he used me.

Then in 1961, I hit .375 or something like that [.379].

But after a while, you don’t take BP every day because you are a pitcher, and you lose a little – you work on your bunting. I was a good bunter. I stayed in the game a lot because I could bunt, and I won games because I could bunt.

Hutch would send you down to the cage in spring training and say, ‘go bunt for two hours.’ They would throw off a live arm and then they would have the pitching machine, and they would tell you to bunt down the first-base line, then bunt down the left-field line.

Then they worked on the butcher-boy play, from Casey Stengel, where you faked a bunt and drew the bat back and hit the ball. If the third-baseman was charging, you tried to hit the ball right down his throat.

You just learned – it was all a fundamental part of the baseball game.

But you didn’t sign a contract right after high school.

I had all these scholarship offers to go to college. My grades weren’t quite good enough to go to Stanford — they wanted me to go to Menlo Junior College, which is a prep school for Stanford – USC, Cal, UCLA. My Dad was sort of my agent. He was a businessman; he had his own car business.

We talked to 16 scouts – from every ballclub – and they were throwing money around like $40,000 or $50,000 bonus money, and this and that. And my dad said, ‘he’s not gonna sign for that. He’s worth more money. He’s worth $100,000. He’s going on to college.’ So I never signed.

If my Dad wasn’t there, I would have signed for a Hershey bar.

I didn’t understand financial stuff. I had no clue what kind of marketing value I had. But I guess my Dad did.

So I went up to Cal, and I was there for one semester, and I didn’t like it. I made the freshman basketball team, but I didn’t like Cal. It was like being a small fish in a big ocean. It was a huge campus.

So I moved back at semester break to Fresno City College, and I started playing there.

SIGNING WITH CINCINNATI — AS A PITCHER

And you converted from a shortstop to a pitcher.

I got to pitch a little more, and I was doing quite well. Bobby Mattick was the head West Coast scout for Cincinnati. He signed Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson from the Bay Area, and Jesse Gonder and Mel Queen. He came into Fresno and called my dad and said, ‘we want to sign him.’ So we went over there, and they had the contract out, and I signed a big deal with Cincinnati on April 1, 1959.

At that point, you really hadn’t pitched that much.

Very little – I pitched maybe 20-25 innings.

You were a three-sport guy before. Was baseball always #1, or did that develop as you developed?

I would say baseball was number 1. I was a quarterback for my sophomore and junior years of high school. Then the scouts started coming around, and they were offering some money, even though they weren’t supposed to, and they were interested in signing me. So my senior year, my dad suggested that I sit out football, but I played basketball. I was a three-year basketball guy.

I liked basketball too, but I knew I didn’t have the ability to play pro basketball. Baseball was always my priority sport.

Seems like you made the right choice!

Yeah, I would say so. I had only pitched 35 innings, and the first year [1959], because I had signed a major-league contract – I never had a minor-league contract, so I was on the 40-man roster to start off with – so that meant they couldn’t send me any lower than class B ball. In those days they had rookie ball, D, C, B, A, AA, AAA, and the majors.

And you went to Topeka in B ball.

It was a pretty fast league, because you could have more veterans on your team. Johnny Vander Meer was my manager. I don’t know how many innings I pitched [124] but there was no pitch count on me. They kept a chart that tells how many pitches you threw; they gave it to you the next day in your locker, and sent a copy to the front office, so they could see what was going on.

I had never pitched, and there was no pitch count on me.

Why can’t these guys today throw 130-135 pitches? I don’t know.

You were in 25 games, with 14 starts. Was that a situation where your body wasn’t used to throwing that much? That workload? Was it tough on your shoulder or arm?

Everybody has a sore shoulder, or a lot of guys had [sore] elbows. You throw a baseball overhand, and it’s not like you’re a softball pitcher and throw underhand, with a natural motion. When you pitch overhand, there’s a lot of strain on your shoulder – you’re going to get stiff and sore. I don’t care who you are.

I didn’t start too many [in Topeka], but my type of pitching – I was sort of a power-type pitcher — and I’ll guarantee you I threw 130-150 pitches.

These guys today, I don’t understand their theory behind [pitch counts]. They say they have too much money invested in them; they don’t want to put too much pressure on them; or whatever it is. To me, I don’t really see where they are coming from. I think they just protect them – in the long run, it doesn’t do them any good.

Starting pitchers today should be throwing at least 125-130 pitches. Then if a guy’s getting hit, it’s a different story—take him out if he’s off or having problems that day.

Hutch used to tell us, ‘you starters, go as hard as you can for as long as you can. The hitter will tell me whether or not I need to take you out.’ It’s a whole different deal today, really.

Do you think they’re protecting their investment? Is money the problem?

I think that’s their thinking. I don’t know what good it does. I would rather have a starting pitcher who could win 20 games.

Remember when Tim Lincecum pitched for the Giants? He was on about a 100-pitch count, and he struck out a lot of guys, so he would get to 100 pitches by the fifth or sixth inning, and they would take him out. Then they would need four relievers to come in and finish the game. But rarely will all four guys be ‘on’ at the same time; a couple of them will give up runs. But maybe your team doesn’t score more runs; maybe it was 3-1 when he came out.

A couple of those years, he should have won 25 games. Instead he won 14-15, just because many times, all he got was a workout [no decision]. The relievers let in the runs, they tied the score, and Lincecum just got a workout.

You have a better chance to win if you pitch into the seventh or possibly the eighth inning. Then you put your closer out there. We had Clay Carroll, Ted Abernathy, Wayne Granger, Jim Brosnan, Bill Henry. Sometimes they would pitch two innings, and they would shut ’em down most of the time.

In 1960, you went to AA ball in Nashville, and you were 14-5/2.79.

In a little more than half a season, I had 165 innings, with quite a few strikeouts [162] and a lot of complete games [15] or at least 8 innings. In Cincinnati they kept a pitch count, and my average for nine innings was about 135 pitches.

In Nashville, you started working with Jim Turner as pitching coach. He said you were able to develop a better breaking ball, and better control. Was that simply repetitions, or something he found in your motion?

I think it was just a matter of pitching more; getting more acclimated to pitching. I know I had a hard time getting my curve ball over for the first two or three years. I had a terrific curve ball, but as far as throwing it for a strike, I wouldn’t throw too many.

As I kept throwing more curves, Jim Turner told me to back off on it – instead of throwing a hard curve, throw it maybe 60 percent. I could get that curve ball over more, but it didn’t have the sharp 12-6 break like the hard one did. The hard one was tough to hit. I used the other curve as my changeup.

You get big swingers like Eddie Mathews or those guys, you throw that ¾ curve in there and a lot of them wouldn’t do much with it; it gave me another pitch.

I never did have a decent changeup. If I had learned how to throw a decent changeup, it’s hard telling how many I would have struck out. [Reds pitcher] Gary Nolan [story here], that’s all he threw – that fastball and the changeup he had. Man, the hitters would go nuts.

Did you try different kinds of changeups, and you just couldn’t get comfortable with one?

I did. I tried all different grips; guys worked with me. I could throw the change, but I telegraphed the pitch. My motion would slow down.

THE BIG LEAGUES

You go 14-5 and get called up to Cincinnati. You face the Dodgers in your first game: one run in seven innings. Their manager, Walter Alston, was quoted, ‘this kid’s really going to be something when he gets the curve ball over more consistently.’ So I guess even he was on the alert about that.

That’s usually the way it is. With just one pitch, you’re not going to get by at that level. You need another pitch or two.

Now they want to screw around with five or six types of pitches: cutters, sinkers, cross-seamers, with the seams, sliders. And they’re having trouble throwing 2-3 of them over, so what difference does it make?

Juan Marichal was a guy who could throw any of those pitches over the plate on any count. That’s what made him really effective. Same type of pitcher as Greg Maddux .

Did you have the two basic fastballs, two- and four-seamers?

[Emphatically] No! I just had the two-seamer. That’s all I ever threw. I wanted my ball to move. You start throwing four-seamers and it straightens it right out.

I don’t know what their thinking is behind that four-seamer. I know from being a shortstop, they said, ‘if you need to make the long throw to first, you want to have the four seams, so the ball won’t sail on you.’

When a guy throws a two-seamer, you got some action on the ball.

I recently watched a video of your no-hitter against the Cubs, where you threw 187 pitches. You said in an interview after the game that [catcher] John Edwards said your fastball moved more when you got tired.

When you wear down a little bit, if you threw the ball below the belt, my ball would take off and dive. If I threw above the belt and I was throwing good, I could get a little hop or rise to it – up-and-in to a right-handed hitter.

Pitchers don’t challenge hitters enough today in fastball counts. In my era, you take Gibson or those guys, if they went 2-0, you’re going to get a fastball: ‘Let’s see you hit it.’ Now they throw a changeup or slider or something offspeed.

You look on the radar gun and a guy is throwing 96, and he wants to trick somebody, when he’s throwing 96? It doesn’t make sense.

If you get to 2-0, try to throw a low strike, right down the middle. Your ball will run, and a lot of times they will pop it up; sometimes they get a base hit off it, but that’s still better than throwing a slider or changeup for ball 3.

If I was 2-0 on Willie Mays, he’s getting a fastball. And he knows a fastball is coming. And I’m going to say to myself, ‘see if you can hit it.’

And you did well against Mays: .172 for his career.

I had good luck with Willie Mays. I don’t think he liked to hit off me. But Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell, they were tough outs for me [McCovey was .324 career, with 5 HR; Stargell was .281 with 6 HR]. Lefthanded hitters, and they were very good hitters, with power.

Do you think lefthanders just saw the ball better off you than righthanders did?

I don’t know; they were just tough outs. Certain guys, you could just throw your glove up there and they couldn’t hit you; that’s just the way it was. And if they hit something good, it went at somebody.

It was guys like Denis Menke — maybe a .260 hitter, but I had a hard time with him. Lots of guys threw sliders to him, and he would swing through them; but I didn’t throw a slider. If I didn’t get my curve ball over, he hit the low fastball pretty good, and he’d get a base hit off me.

Roberto Clemente didn’t like to hit off me, either [.261 career, with 16 strikeouts in 72 at-bats.].

The Reds won the pennant in 1961, but that season was up-and-down for you. You got into 27 games, but only 11 were starts. Were there physical problems in addition to going back-and-forth between starting and relieving?

No, I was sort of used like a fifth or sixth starter, if we had a doubleheader or something  and they needed an extra pitcher. So I was a spot-starter and long man in the bullpen – pitch four or five innings if someone got knocked out early.

and they needed an extra pitcher. So I was a spot-starter and long man in the bullpen – pitch four or five innings if someone got knocked out early.

And you made one appearance in the World Series.

Yes, I didn’t do any good there. I was so nervous, I couldn’t see straight. I relieved Joey Jay on the last day [the Reds lost to the Yankees in five games]. I don’t think I stopped anybody, either.

So it was nerves, as much as anything, just being in the World Series?

Yes, it was something you dreamed of as a kid. I was only 20 or 21 years old. It was a whole new thing to me.

You spent all of your early years in the big leagues with Fred Hutchinson as your manager. You said he was the best manager you ever played for. What are your thoughts on him now?

A great man. A great leader, and a great man. He didn’t say a lot of words, but when he talked, you listened.

When I came up, I didn’t say anything anyway. The players told me to shut up and listen and take direction. So that’s what I did, until I started having some success. Then I sort of blended in and became a veteran and could voice my opinion.

It was not easy for rookies in those days.

It was a little like fraternity hazing. [Catcher] Ed Bailey was on my case all the time when I first came up, calling me Moneybags and that kind of stuff. But Wally Post and Gus Bell, they took me under their wing they watched out for me; they were wonderful guys. They took me to dinner a lot on the road, and they told me how to go about being a major-leaguer.

Ballplayers get on each other anyway, in a way that sees if you can take it. I wasn’t used to being heckled. Bailey started hammering on me right off the bat, and I didn’t know how to take it, so I didn’t say anything. But I took care of it after a while, and I didn’t have any problems with Ed Bailey anymore. He became a regular guy and a fun guy to be around.

You ended up starting the year in AAA in 1962. How surprised were you?

I had no clue. I finished spring training, and I had done well. At the end, Hutch called me in. I had already used two of my options; I had one left. [GM] Bill DeWitt was in the office, and they said, ‘here’s the deal: you should be on the club, but you have an option left, and we have to protect two guys. It’s a business deal, and we’re going to use your option. Just go to San Diego for a short period of time, and we’ll bring you right back.’

I had just gotten married, and we were there in Tampa, and I couldn’t believe it. We had to get in the car and drive to San Diego. We made it in about four days.

In San Diego, I lost my first game and then won maybe four in a row, and I got recalled. The Padres’ GM flew my wife and baby to Cincinnati first-class.

Did you feel more established, that things were moving up?

I felt that I knew I could pitch at the big-league level by that time.

I was probably brought up too early the first time; I was sort of overwhelmed in 1960. I didn’t realize where I stood as far as my ability, compared to the hitters. In 1961, I was there the whole year, and I added some things I did well for the ballclub. I was getting more confidence. Coming back up in 1962, I knew I was going to be able to put up some decent years.

In 1963, you won 23 games. Was there anything different for you, other than confidence?

I just think I had a lot of games whether I had hitters overmatched, and I knew it.

In 1964, you were 15-10, and had an even lower ERA than in 1963, but run-support was a problem.

In 1963 there were games where I gave up 4-5 runs, but we won. It works that way sometimes.

You pitched to decisions many times, instead of pitching five or six innings as they do now, with relievers getting the decisions.

That’s the way it should be. But every club does it the other way now; they all basically manage the same way, like cookie-cutters.

You take a guy like Vada Pinson—he didn’t care if it was a lefthander or righthander pitching. And [Reds lefthanded pitcher] Jim O’Toole told me one time, he had a slider that he would throw to righthanders to jam them – he could just about tell them it was coming, and still jam them.

So we went to Pittsburgh, and he starts the game. They had all righthanded hitters in the lineup, except Bob Skinner and Willie Stargell. O’Toole threw a three-hit shutout — and Skinner and Stargell got all the hits.

The strategy is just way overplayed. They’re big on computer stats. It’s just – something else.

My deal on pitching is, if you are a righthander who can’t get righthanders out, or a lefthander who can’t get lefthanders out, you better go on and try something else; you don’t belong in the league.

A TROUBLED 1964 SEASON

How was that 1964 season, with a tough pennant race and Hutch battling cancer?

Hutch’s health deteriorated as the year went on. It was a bad scene. It was terrible. Hutch had so much pain that Reggie Otero had to dress him and help him out to the dugout. He was in so much pain.

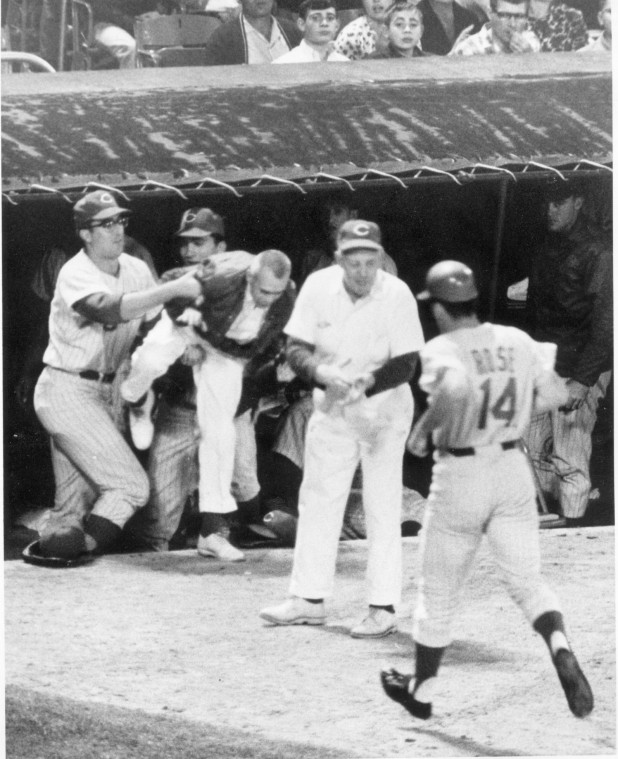

With his health failing rapidly, Fred Hutchinson turned the Reds over to coach Dick Sisler in August 1964. The Reds rallied as the Phillies collapsed in late September. But the Reds lost the final game 10-0, and St. Louis won the pennant. The decision to pitch John Tsitouris instead of Maloney in the final game has been debated ever since.

The last game, we got beat. We had a chance to win the pennant. Jim Bunning beat us 10-0. Hutch just came in and said, ‘I hope all of you have a good winter,’ and he just left. He just didn’t make it [Hutch died November 12, 1964].

Is it a sore spot that you didn’t pitch that last game?

I’ll tell you what happened on that deal: it wasn’t my decision. I was ready to pitch; I thought I was OK. I pitched 11 innings four nights before against Pittsburgh, but we didn’t win the game [The Reds lost 2-0 in 16 innings. Maloney gave up only three hits and struck out 13.]

I told them, ‘I can pitch if you want me to.’ They said, ‘Tsitouris has had good success against Philadelphia. You be ready to go face St. Louis in the playoff game.’ So they went with Tsitouris, and we didn’t score a run; maybe it wouldn’t have made any difference. Maybe I would have hit a home run if I had started [laughs].

TWO NO-HITTERS IN 1965

In 1965, you were 20-9 and threw a ten-inning no-hitter against the Mets, and a no-hitter against the Cubs. At this point, are you feeling like you are at your peak, fully in command?

No, I didn’t feel that way. I felt like I was better than those guys. Not to sound bigheaded, but I felt I had a chance to throw a no-hitter every time I went out there.

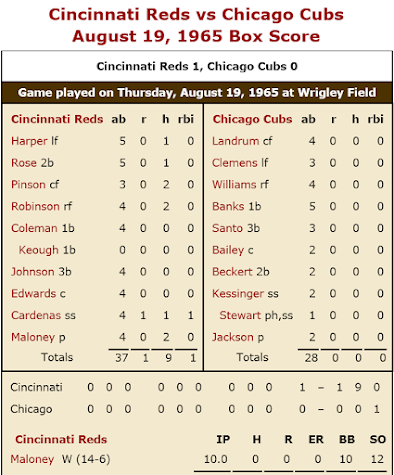

You lost the first no-hitter in extra innings June 14 on a Johnny Lewis home run. On August 19, you went to extra innings with a no-hitter again, against the Cubs.

Billy Cowan, the Mets’ leadoff hitter, went back to the bench after I struck him out, and he said, ‘just forget it.’ I had a bunch of strikeouts, and I got to the 10th inning and we couldn’t score a run. In the 11th inning Johnny Lewis hit a home run off me, so I got beat 1-0.

he said, ‘just forget it.’ I had a bunch of strikeouts, and I got to the 10th inning and we couldn’t score a run. In the 11th inning Johnny Lewis hit a home run off me, so I got beat 1-0.

Then two months later, I’m in the same situation in Wrigley Field. I’m sitting on the bench, looking at the scoreboard. I’ve pitched nine innings and given up no hits. I’m in the same situation as I was with the Mets, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘I don’t want to have the same result.’ I might’ve been the only pitcher in history to throw two ten-inning no-hitters and lose both of them.

And it was lucky. I’m in the on-deck circle, and Leo Cardenas hits the ball, and it hit the foul pole; six inches to the left, and it’s a foul ball.

And Ernie Banks hit into a double play to end the game, after 187 pitches. Did you feel that you sort of had one coming, after what happened to you before?

Oh, I don’t know; you get some breaks and you don’t get some breaks, you know? That’s baseball. That’s what makes it the game it is.

And you had two other no-hitters where you got hurt and had to come out?

Yes. One was in Pittsburgh, and I had a perfect game for six innings. They had an automatic infield tarp that would come out of the ground. There was a hole on the side, and I can’t remember if it was a popup or what, but I hit that hole and twisted my ankle. That was the end. I just couldn’t go any more.

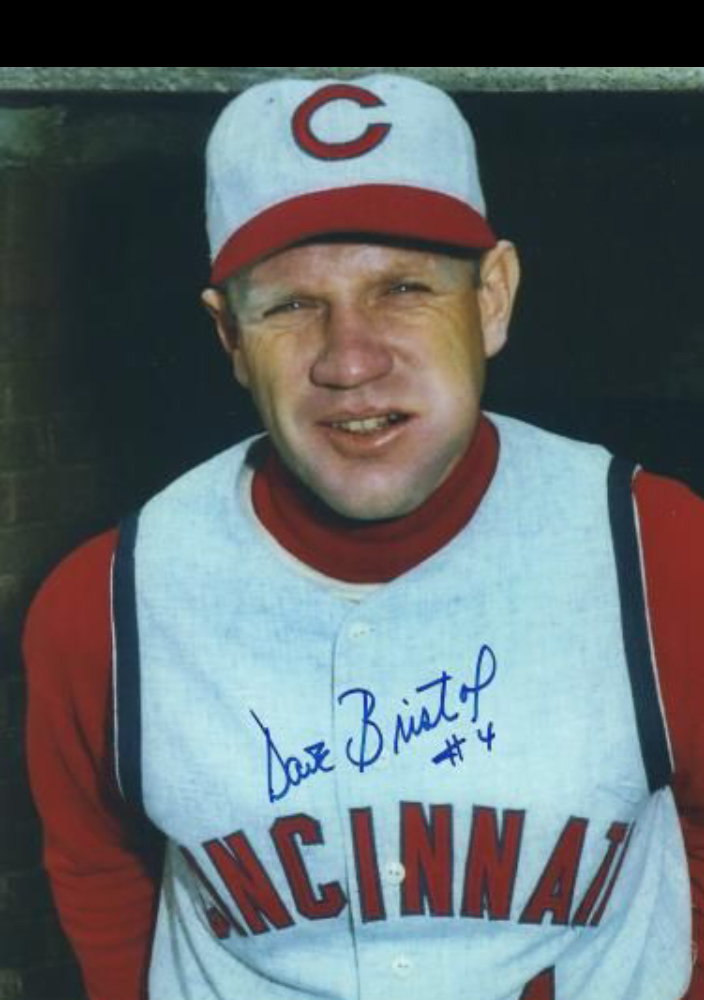

Dave Bristol took over as the Reds’ manger in the middle of the 1966 season. You pitched for him for 3-1/2 years. How was it, pitching for Dave?

A good man to pitch for. A good manager. Fiery-type manager who came up through the Reds’ system.

Reds’ system.

He was a coach under Don Heffner. Bill DeWitt hired Heffner after the 1965 season, and he didn’t last but a couple of months, and Dave took over. It was a good move. He was a fundamental-type guy who wasn’t afraid to confront a guy when he wasn’t doing things right. And he wanted to win.

He was a hard-nosed-type guy, a little like Hutch: they could chew you out for something on the field, fundamentals or whatever, and five minutes later they wouldn’t hold any resentment against you. The slate was clear, and you went on from there.

As you got farther along in your career, were you feeling the accumulation of all the pitching? Were you adjusting to having a lot of innings pitched?

I knew there was some wear-and-tear. I would pitch about 100 innings or so, and the back of my shoulder would get sore, and I would have to have a cortisone shot. I’d miss a start, and then I was good for another 100 innings. As the years wore on, I was starting to have more problems with my shoulder. More shots.

In 1969 I was 12-5, but the first part of the year I was missing starts because of the  shoulder. Then I got started and could pitch OK; the second half I won quite a few games and I still had a good ERA [2.77].

shoulder. Then I got started and could pitch OK; the second half I won quite a few games and I still had a good ERA [2.77].

But there was an ominous development that affected you for the rest of your career – and ultimately ended it.

I started having problems with my heel. The back of my heel was bothering me. I couldn’t run. I told the trainer, ‘there’s something wrong with my heel, and I can’t shake it.’ Of course, the trainer goes right to the general manager [Bob Howsam]. I got ultrasound and all that. X-rays didn’t show anything.

Howsam called me into his office, and I told him, ‘my heel has been bothering me, pitching and running and when I come to hit.’ He said, ‘we had you checked out, and there’s nothing wrong with you. The only thing I can tell you is, you have no pain tolerance. Bob Gibson pitches with pain. You gotta go out there and pitch; we’re paying you a lot of money.’

So I just looked at him and left his office.

I built a lift in my heel, and I pitched the last part of the year. I did pretty good, but my heel was still bothering me. I felt that with the layoff during the winter, my heel would heal up, see.

Then, they wanted to cut my salary $2,000. I said, ‘I don’t want to take a cut. I’ll play for the same money.’ Howsam said no. I said, ‘Well, I’m not gonna do it.’ I was down in spring training, but hadn’t signed. He says, ‘we aren’t going to give you the same salary. Your performance was bad; we’re cutting back; and we are going to cut you $2,000.’

So I said, ‘I’m not gonna play.’

He said, ‘if you don’t want to play, that’s OK with me.’ He had a thing behind his desk, with all of the rosters on little metal tags. He got up out of his chair and took my name off the list, and he folds that metal thing in half and throws it in the trash can. I left the office with my tail between my legs.

That’s cold — to question someone’s durability and desire to pitch. But it happened with Gary Nolan, Wayne Simpson, and others.

That’s sort of the way it was with those old-school guys in those days.

This guy was questioning my pain tolerance, and he doesn’t know what a sore arm is.

Today, my rotator cuff is completely shot. Back then, they would give me a cortisone shot, and if they hit the spot that was sore, it was good. It was like changing the oil in your car; you were good for another few thousand miles.

You never knew precisely what the problem was with your shoulder?

No, they didn’t know. They talked about my deltoid, but they never mentioned anything else.

But you had a change of heart, and you did sign with the Reds for the 1970 season.

I left the office and called my dad, and he said, ‘make your own decision, but you’re making a lot of money. Go ahead and sign your contract. Go ahead and have a big year, and get a raise next year.’ So that was my thinking, and I went back the next day and signed.

It was already 2-3 weeks into spring training, and about the second day, my heel started bothering me again. I never said anything. I pitched with a sponge in my heel. It was bothering me on the side of the heel, where the leather touched that part of the heel. My foot was almost out of the shoe. I was pitching that way; I didn’t want anyone to know.

But you suffered a serious injury in your first regular-season start: a ruptured Achilles’ tendon.

Frist game I pitched in 1970, I hit a ball up the middle, took one big step out of the batter’s box, and it popped. The catcher heard it pop; the umpire told me he heard it pop. I got about halfway down the line and stopped. I thought I had swung the bat and it hit me in the heel. But after a couple of steps, I knew it was bad. So [first-base coach] Ted Kluszewski came over and asked what happened. I said, ‘It’s not good. I can’t walk. I can’t do anything. I got some pain in my heel, bad.’

So they carried me in the trainer’s office, and I went under the knife the next day. I had severed the Achilles’ tendon. I never won another game after that.

AFTER THE REDS

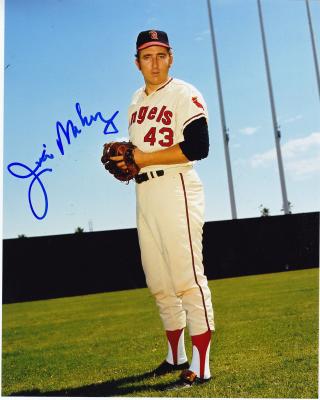

You were traded to the Angels after the 1970 season, but it just didn’t work out. What happened?

I could never get my body to hold up. I started having different types of leg pulls; hamstrings; groin issues; rib cage. It seemed like my body just went south. I could never keep it going.

The Angels gave me every chance to start with them, and I would start going pretty good, and bang! my leg would go out, or my groin, and they would have to put me on the disabled list. Then something else would happen.

To be honest, they should have released me early in the year: ‘see you later.’ But Gene Autry, my boss, he paid me the whole year. That’s the kind of guy he was.

My legs had been the strongest part of my whole deal. When I did the Achilles’ thing, I was in a full cast for a month, then a walking cast, and when they took the cast off, it looked like I had polio — my leg was half the size. My leg never really got strong. I even had trouble going up stairs. It just didn’t have the strength.

END OF PLAYING DAYS

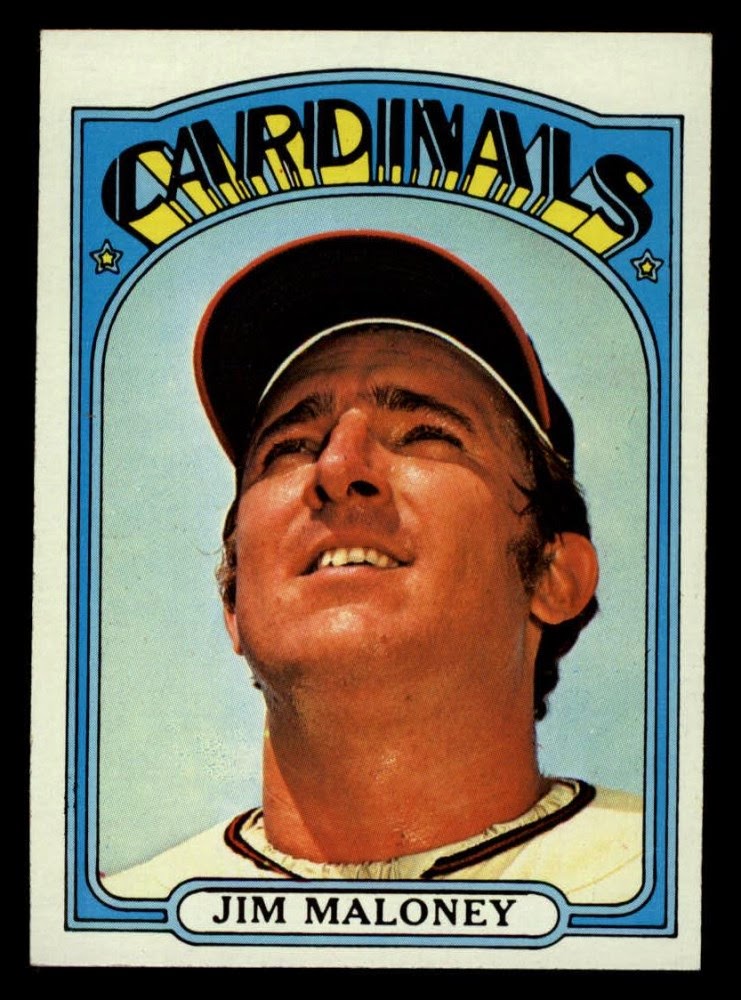

But you kept trying – first with the Cardinals, then the Giants.

The next spring [1972], I called around. I talked to Pittsburgh: ‘we’d like to sign you.’  Meantime the Cardinals called, and I went with them because I knew the trainer, Bob Bauman. I knew he could help me. I signed with them and was doing pretty good in spring training, trying to earn a spot as a starter. My velocity was up, the curve ball was working — no problems.

Meantime the Cardinals called, and I went with them because I knew the trainer, Bob Bauman. I knew he could help me. I signed with them and was doing pretty good in spring training, trying to earn a spot as a starter. My velocity was up, the curve ball was working — no problems.

All of a sudden, they call us in and we voted to strike, and Bing Devine told us they were giving us two hours to get out of town; they were locking the clubhouse doors. I went back to Cincinnati and Bing Devine called me and told me I was ‘on the bubble’ and they weren’t going to keep me, because of the strike thing. They released me.

So with no major-league teams going because of the strike, the only thing was to get a job

with a minor-league team. So I called the Giants, because they had our old [Reds] trainer Al Wylder, and I knew he could help me.

But I had to go to Phoenix first, so I went there and went 5-1. But I wasn’t throwing the ball like I could. I was pitching different. I was pitching more for contact than power, but I was getting those guys out.

I told manager Jim Davenport, ‘I’m not staying here all year. If they’re going to call me up, I want to find out. If not, I’m out of baseball.’ So he checked with [Giants owner] Horace Stoneham, and they said if I hung around, they might bring me up toward the end of the year.

I said, ‘that’s it.’

I went to the clubhouse, packed up my stuff, gave my shoes and glove to the clubhouse kid, and got on a plane to Cincinnati. And that was it.

I just wasn’t going to hang around. No big fanfare or anything; I just left.

In Part 2 [here], we look at the challenges Jim faced — and ultimately defeated — in life after baseball.