Kim Nuxhall dreamed of being a big-league baseball player like his father, Joe. That dream did not come true, but the life lessons he learned from his famous father shaped him and  his life — long after his playing days were done.

his life — long after his playing days were done.

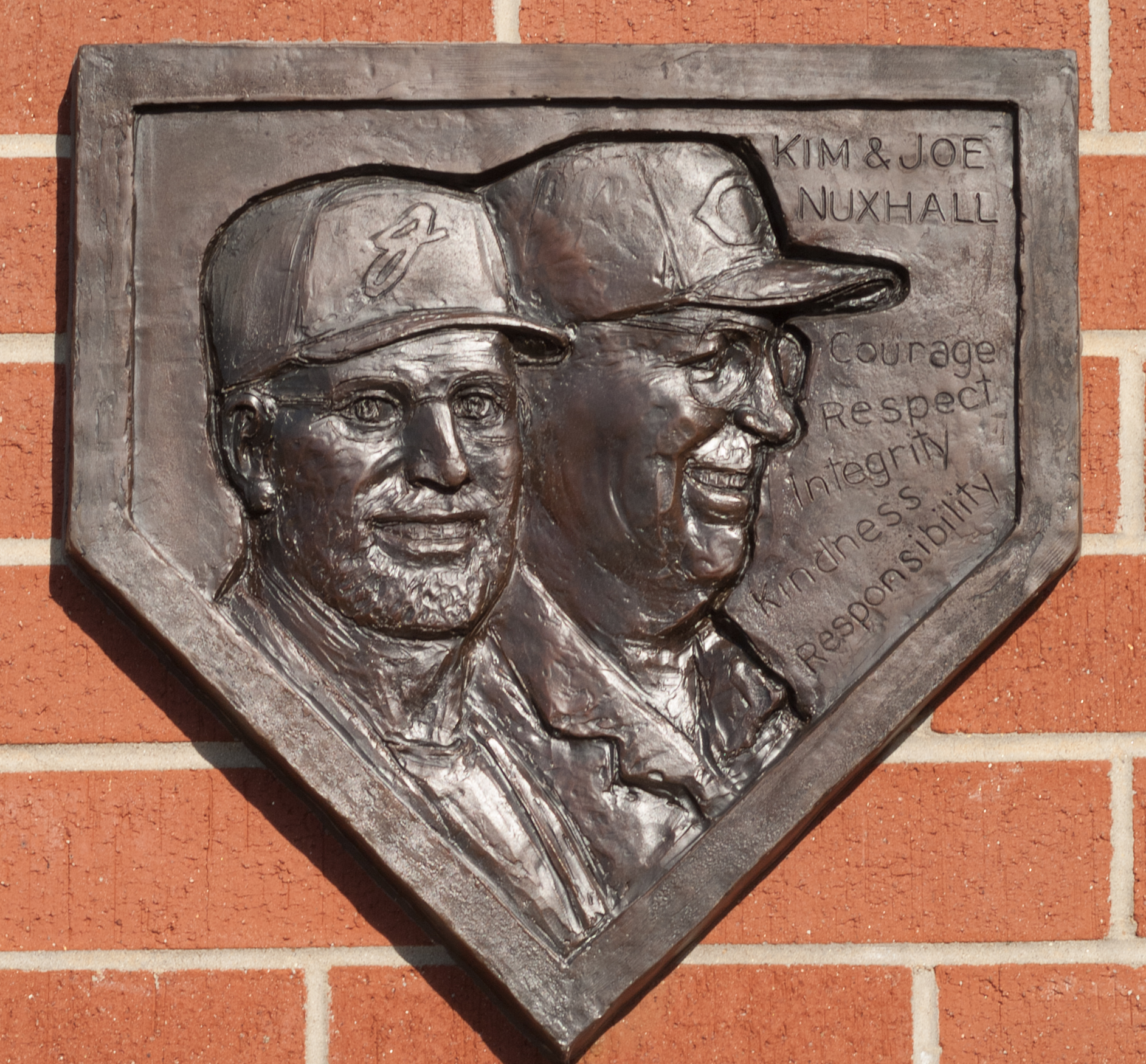

Kim spent 32 years as a physical-education teacher before he turned his focus to the Joe Nuxhall Hope Project, which serves to continue the “legacy projects” of his late father. He oversees the Joe Nuxhall Character Education Fund; the Joe Nuxhall Scholarship Fund; the Reds Rookie Success League; and the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Fields. He is Chairman of the Board of Directors for the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League.

He seems to be in perpetual motion, constantly working on several of these legacy projects at the same time. He is one of the most dedicated and hardest-working people you will meet.

We sat down recently for a look back on his playing days; his teaching career; and his great passion: character education for youth.

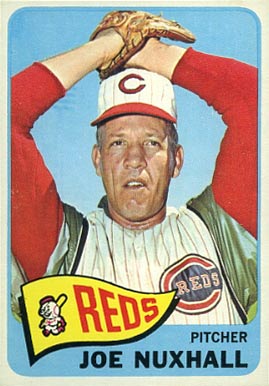

GROWING UP NUXHALL

How tough was it in those days to be the child of a celebrity? Were you “Joe’s son” – you and your brother Phil?

There was a point where I thought about changing my name to Little Joe. At that time,  Dad was still pitching, and he was a hometown guy, based in Hamilton [Ohio], and he was quite popular — so the spotlight was on us all.

Dad was still pitching, and he was a hometown guy, based in Hamilton [Ohio], and he was quite popular — so the spotlight was on us all.

People would say, “oh, you’re Joe Nuxhall’s son.” And everyone was looking at you. Even in Little League. It was a “character-building” experience [laughs].

I think it drove me more to be a hard worker. Even after I signed with the Reds, there were those who thought I was signed because I was Joe’s son; and that could partially be true, because they looked at my Dad and thought or projected that maybe I would end up with his size and ability. That didn’t happen. [Joe was 6’ 3” and 195 pounds; Kim was 5’11” and 180 pounds.]

I went into kind of a shy shell – I was kind of introverted because of that – really, all through school I was considered shy.

And did sports get you out of that?

Yes, in general. I really liked basketball, but I was never comfortable being out in front of people. In baseball, I was as comfortable as could be. In football I had a helmet on, so it didn’t bother me. I was chronically shy as a kid.

In high school, you played football as well as baseball. Was baseball always first? Did it come naturally, or was that intentional?

I never felt any pressure; I loved playing baseball. The only pressure I felt from Dad was to work harder than anyone else; to be the best I could be.

We lived in a perfect neighborhood growing up – all of us played all the sports, and we just went from season to season. I loved all sports.

But your Dad never emphasized baseball over other sports?

No, he was a multisport guy too. He encouraged that – it was sort of the opposite of  specialization. It’s how the culture was back then.

specialization. It’s how the culture was back then.

Did you develop more in high school for baseball? Was that a natural progression for you?

When I was about 14, Dad started letting me throw a curve ball – he wouldn’t let me throw breaking pitches before that. And I always got to go to spring training. Joe Bowen, a scout for the Reds, noticed that I had good-sized hands – they liked that, and they sort of kept an eye on me.

I broke my arm in football when I was a sophomore, and that set me back a little bit. And I was young when I graduated – only 17.

So they projected a little bit of your Dad onto you?

I think that’s exactly what happened.

But you had also built a mound in your back yard, didn’t you?

Yep! When I was 11 or 12 years old, I was wanting a place to throw, and Dad said, ‘there’s the wheelbarrow, and there’s a shovel.’ And up the street was a farm, and I remember having a little booklet that showed the dimensions of the mound – the grade and all that. I hauled every bit of the dirt.

I threw every night I could to Dad. And when I look back, I have great memories of tossing in the backyard to my Dad.

I always threw at the major-league distance – I didn’t throw at Little League distance, and it made a difference. And all I threw was an overhand fastball. Eventually I learned a two-seam fastball that I could throw low-and-outside [to righthanded hitters].

Was going to spring training in Tampa the biggest advantage you had?

No doubt.

And the Reds would have workouts at Riverfront Stadium for all of the potential draft picks in the Tri-State area [Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky]. I probably had my best day ever at one of those, when Joe Bowen told my Dad that I would be a high draft pick – which unfortunately, I wasn’t.

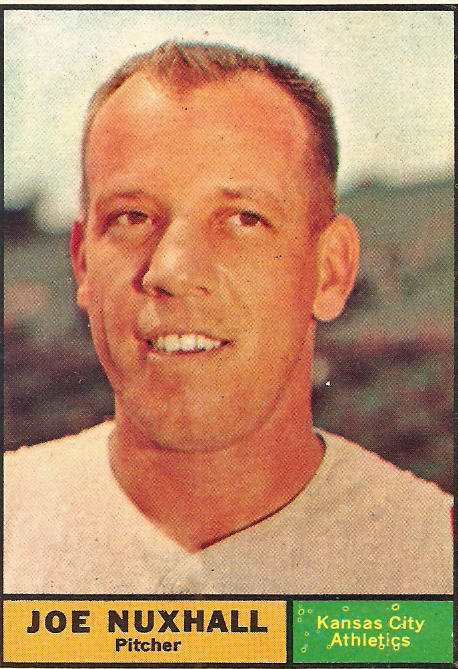

And when you were younger and your Dad was traded to Kansas City, you didn’t want to go?

I remember it vividly. I was standing in the kitchen, and my Mom said, ‘your Dad has been traded to Kansas City.’ And I was an independent little kid at age 6, and I was ready to stay back by myself.

But you did go to Kansas City, though it was for one season.

It was a pretty neat experience [in Kansas City], actually.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL

How did the signing process work for you? I assume this is right at the end of high school.

I wasn’t drafted; I did not have a real good senior year, although our team did. I went to the tryout, and I really had it that day. I was all set to sign at Gulf Coast Junior College in Florida, when I went to the tryout, and I really had it. I always wondered, though: is this because of Dad? That was always in the back of my mind, anyway. I would have signed for nothing. I would have paid them. They didn’t know that.

But when they offered $5,000, I knew they were serious. So I signed and was on my way to Bradenton, Florida.

Kim was 1-3/5.71 in 10 games for Bradenton in 1972, and 1-2/10.29 in eight games in 1973.

Were you exclusively a pitcher then? And control was key for you?

Yes. It wasn’t a lack of hard work. They weren’t going to give me six or seven years in the minors to figure it out. I wasn’t showing progress. I was so erratic. The best game I pitched was the last game I pitched.

In A-ball with the Seattle Rainiers in 1974, Kim was converted to shortstop. He hit .231 in five games before he was released.

Baltimore was somewhat interested, but I never heard back from them.

So I was released, came right home, and played with my old summer-league coach. Finished out that summer, played the following summer, opened up the batting cage in 1976, and tore my rotator cuff after that. I didn’t play anymore; I wouldn’t have been able to.

What’s the feeling like to be staring at the end of your playing career at such a young age? Try again or get on with it?

I was devastated, because it’s what I had always wanted to do. But in the off-seasons I had been going to school at Miami University, and I tore my rotator cuff in a volleyball class. I played one more season of summer ball, and I wish I had stuck with that, because I started making some progress.

AFTER BASEBALL: TEACHING

What led you to go the education route?

A friend of mine was a Phys Ed teacher at an elementary school, and he asked me to help him as a volunteer and help coach fifth-grade boys. I really enjoyed that. I liked all sports, and I enjoyed working with kids. It seemed like the natural thing to do.

You developed an interest in character education, as a way to make a difference in your teaching. This was something you sensed a need for and stepped in to fill a void?

During the second half of my teaching career, I had somewhat of an epiphany about that. It reinforced some of the things I was doing, and it lit the fire toward character education.

It reinforced some of the things I was doing, and it lit the fire toward character education.

But you had to sell that to your administration at first? It seems like such an obvious benefit, but you found resistance to that.

The challenge now is that there is so much emphasis on testing and test results that to add another thing to their plate – it’s unfortunate, because the idea was to teach character first, in elementary school and kindergarten.

FAMILY

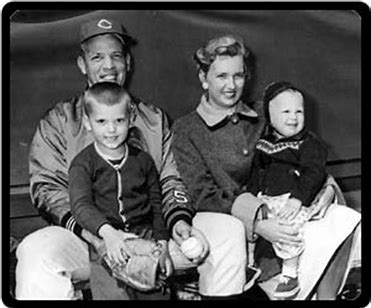

We’ve talked so much about your Dad and his example, and how he influenced so many things you did and still do. What’s your Mom’s role in all this?

Mom is a pretty amazing person when I look back, being the spouse of a ballplayer and celebrity. That’s challenging, so I think I saw how Mom had amazing grace, really. You’re at a restaurant and you become invisible; that’s not easy.

She was able to establish and maintain her own identity? She was not ‘Mrs. Joe’ — she was Donzetta?

Yes. She was very patient, where Dad was impatient—he had that competitive spirit about him. She was the patient one of the group.

Was she doing the bulk of the child-rearing?

Yes. She was a quiet disciplinarian.

You mentioned that your brother, Phil, took a different route.

It was harder for him, because he didn’t take the athletic route. But he was probably as gifted musically as Dad was athletically. And he has a passion for helping kids as well.

CHARACTER EDUCATION AND THE MIRACLE LEAGUE

So you played ball, finished that, started teaching, and progressed to character education. Then you started taking on more of your Dad’s vision or legacy projects: golf outings, scholarship programs, etc. Did you feel that as your Dad got older, you had to step up? You have your fingers in so many pies now.

I guess it was a combination of handing me some of the torches and lighting a few new ones. He started the golf outing himself, to award scholarships. I think if he had any regret, it was that he didn’t get to go to college.

How did the Miracle League project come about?

We were watching HBO, and they were doing a story about a girl in Georgia with Brittle ![]() Bone Disease. She would come home with the paperwork to play soccer or softball: ‘why can’t I play?’ Her mother and some townspeople got together and had a simple, brilliant idea to build this park called the Miracle League.

Bone Disease. She would come home with the paperwork to play soccer or softball: ‘why can’t I play?’ Her mother and some townspeople got together and had a simple, brilliant idea to build this park called the Miracle League.

We looked at each other, and without saying anything, I knew he wanted this to happen in Butler County [just north of Cincinnati]. He saw the plans for it, but unfortunately, he passed before the park was built.

A place where every kid, with every challenge, gets every chance to play baseball.

The complex opened in 2012, with a  tremendous amount of volunteer help.

tremendous amount of volunteer help.

It’s an amazing story. We drudged along for six years trying to raise money. Then I ran into some high-school football buddies, explained what we were trying to do, and things started to happen. And with the help of a former teammate at the Hatton Foundation, we got a grant for $500,000 that really got things going. Now we have players from ages four to 74.

The next project for the Miracle League complex is a nine-hole wheelchair-accessible miniature golf course, scheduled to open in 2019.

What inspired the mini golf course?

I was operating a mini golf course that we closed when we started construction on the Miracle League. I saved some of those obstacles, and we thought we would save them for a wheelchair accessible mini golf course – one of the first of its kind in the area to be totally wheelchair-accessible.

You never stop dreaming. What’s next for the complex?

We’re looking at having a sort of pseudo zip line that’s wheelchair-accessible. That may or may not happen.

But the granddaddy is the gym.

The biggest legacy project of all is a full-size gymnasium for special-needs athletes, which will include an exhibit of Joe Nuxhall memorabilia that illustrates Joe’s lifelong commitment to help others. It’s on the drawing board, but raising funds for such a large project has been challenging.

It will be open year-around, for Special Olympics basketball, wheelchair rugby and volleyball, and so visitors can learn about Dad.

I understand you want to have a sort of Visitors Center that’s like a timeline that weaves through his view on kids and desire to help?

What are you going to do with that celebrity? You use it to help others.

Yes. He lived his whole life as a reluctant celebrity. So the idea is, ‘what are you going to do with that celebrity?’ You use it to help others.

THE NUXHALL LEGACY

Has that ever been a burden, being Joe’s son as an adult? Is it OK being Kim Nuxhall?

It’s mostly a blessing. The fundraising part of it is daunting.

Is the Nuxhall legacy something you have grown into, that you are more comfortable with? Was it ever uncomfortable for you?

With privilege comes responsibility. It’s a privilege to do this, but it does come with a lot of responsibility.

Which is the most important of the legacies?

By far, the character-education piece. One of the things the Character Fund supports is the Reds Success League of Butler County. And we have partnered with the Reds Community Fund for twelve years.

But nothing else would have happened without those traits in my Dad, witnessed by me growing up. If I didn’t develop a passion for others, why would I grow up to help others?

All those experiences being Dad’s son, I was fortunate to learn from that. What if you are a brilliant student, but you are not a good person? You didn’t learn self-control, or discipline, or how to respect other people? Compassion? Empathy? That’s the essence of it all.

I always imagine ‘what if?’

What if kids worked harder? What if kids respected others more? What if kids were more responsible?

To me, bullying is a simple lack of compassion. What person do you know who has a high level of compassion and empathy and is a bully? None.

It’s the fundamental issue in our culture right now.

For more information: