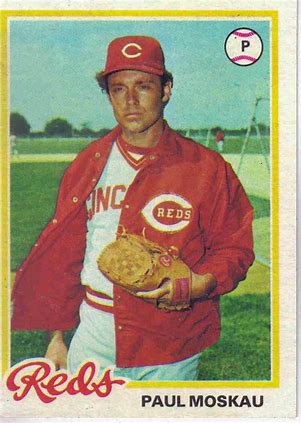

Paul Moskau was part of a “new wave” of Reds players who came along as The Big Red Machine was winding down. The idea was  that Paul and Mario Soto and Paul Householder and Duane Walker and others would sustain what the original BRM had established during the 1960s and 1970s. But things don’t always work out as planned, for the team and for individual players.

that Paul and Mario Soto and Paul Householder and Duane Walker and others would sustain what the original BRM had established during the 1960s and 1970s. But things don’t always work out as planned, for the team and for individual players.

And as so often happens with pitchers, injuries derailed Paul’s once-promising career. He’s now happily retired in his native Arizona with his wife, Anna.

Part 1 of this interview deals with Paul’s baseball journey, and life after he could no longer pitch. In Part 2, we’ll talk old-school baseball.

Paul Moskau Growing up in Tucson where I did, we got The Game of The Week. That was it. I’d sneak out of school to go to spring training. We’d go up there and walk around the complex and look at these guys and go, holy cow, look at these guys! That was my exposure to it. Maybe that’s where I fell in love with the game; I don’t know.

JH Were you always a baseball guy, primarily?

Yeah, I didn’t — they wanted me to play football, because I was fairly big in high school, and I just couldn’t understand the thought of going out there, trying to hit somebody while somebody else, a bunch of guys are trying to hit me, too.

JH It didn’t really appeal to you, for some reason? [laughs]

PM No, I liked baseball. I liked golf, but I didn’t play that very much. But I just always played baseball. I don’t know why I did. I just did. That’s all I remember as a kid. That was the sport.

JH I grew up a huge Reds fan. I remember you well, as a hot prospect coming up in the mid-1970s. And so —

PM I was one of many who didn’t quite fulfill their expectations. [laughs]

I was drafted [by the Reds] in 1975. And they sent everybody, at that time, up to Billings. That’s where you reported once you signed, up to the rookie club. So we were there and getting ready and working out — you know, meet the other guys that were drafted, the kids that were coming there. I guess there were some maybe extended kids or something from spring training.

I got to pitch the first game, then I get a call, and they told me I’m being called up to Eugene. And I guess it was because I was 21 and I was the third [-round] pick in the draft.

Paul then became part of the Class-A Eugene Emeralds – the “Little Red Wagon” compared to the big-league Big Red Machine. The 1975 Emeralds won the league championship, and those players formed bonds, on and off the field, that are still treasured – and celebrated – today.

PM I guess they figured maybe I could go over there with some older guys and fit in. I remember going out on the mound in Eugene to throw, and guys were just kind of, everybody was watching this: “well, here’s the new guy; let’s see what he’s got” kind of thing.

I remember that instance, and then we left on a road trip, and we went to Seattle. And they played in the old Seattle baseball stadium — I think it was called Sick’s Stadium — where they used to play years ago.

JH Where the Pilots were.

PM Yes. And so Greg [Riddoch, Eugene’s manager] had heard that I could hit a little bit, but mostly played [other positions] in college and pitched, both.

So in that first game, I guess it was a doubleheader, he pinch-hit me. I hit a home run, and we won the game. Then in the second game, I think Lynn Jones pinch-hit, and he hit a home run, and then it seemed like from there it just went.

The thing I remember most [about Eugene] was going to the ballpark early for early work, BP, whatever; treatment, that kind of stuff. We would get done and then just kind of lay down in the outfield on towels, just talk baseball, and shoot the breeze. And I said, “God, this is professional baseball! How cool is this?”

And there were some [future] big-league guys in the club, right? Larry Rothschild came just after I did, and Lynn Jones, Mario Soto, myself, Greg. There were older guys; maybe that’s why guys fit in better.

It wasn’t what I expected of professional baseball, where it was kind of — everybody’s looking at everybody else’s stats, and see who’s sucking worse than the other guys, where they can think to get a chance to move [up to a higher classification].

JH It’s a dog-eat-dog kind of deal.

PM Yeah. And it didn’t seem like that to me. Maybe I was in a fog about it; I don’t know. I don’t think so. I just think everybody just truly enjoyed each other.

I guess it’s what people would want professional baseball to be. Where you kind of play as a team, you pull for each other, you care about each other. I mean, it was really unique.

And then I just had a really, really good season [10-2, 7CG, 1.53 ERA in 88 IP].

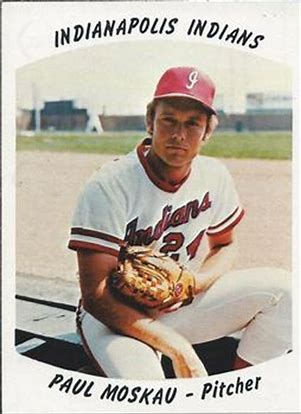

In 1976, Paul played at AA Three Rivers in Canada. He bypassed the usual “next step” of playing higher-A ball at Tampa. He was 13-6 with a 1.55 ERA and 11 complete games. In 1977, he was 7-1, 3.56 in a half-season at Indianapolis [AAA].

PM I blew through the minor leagues, and I wonder if I didn’t — I never struggled, is what happened. And I just blew through A-ball that short-season, and I went to Instructional League and had a great Instructional League, and then went to one minor-league spring training, is all I went to. And then after that, I was invited to big-league camp. And then I guess — I didn’t know — I guess I was the last guy cut [from the big-league club] in 1977.

I struggled in the big leagues, but I never struggled in the minor leagues.

JH You were 10-2, 13-6, 7-1 in the minors; that’s pretty strong.

PM And my ERA was like 1.50 the first two years. [laughs]

JH And hitting .300 in the minors, too. I mean, —

PM Yeah, because I was still able to play [a position], and they knew I could hit. I don’t know if it was Greg or my AA manager who asked [the front office] if I could play first base one time, to give somebody a rest. They told him no, because I was pitching so well. And I was really excited that maybe I would get a chance to play again, because I could play a little bit.

JH What other positions did you play before you became exclusively a pitcher? You mentioned that you had played in college on days you didn’t pitch.

PM I was an outfielder-first baseman. I probably was better at first base than most anything. I played all over the place in high school, like third base. Outfield mostly is what I played in high school, and pitch.

JH Were you the guy who was the “best athlete on the team, so you played all over the place” kind of thing?

PM Well, I wasn’t the fastest guy; I think I was just the most consistent guy. Like in high school, I think I was just the most consistent at lots of things. There were guys who were faster and guys who were stronger. Guys who threw harder.

There were no radar guns back then. Nobody knew how hard they were throwing. You just go there and try to get guys out the best way you can. That’s all I knew.

JH Was a lot of your youth ball spent as a pitcher? How did pitching develop for you?

PM I was a pretty good athlete, and I could throw strikes, is probably basically what it was. So I pitched in Little League, Pony League, Colt League. Pitched and played [other positions] in high school. So it was just kind of a part of my life, and my makeup. I didn’t really see it as — other guys played, other guys pitched and played other positions. It just didn’t seem like it was anything that was that unique.

I wasn’t particularly a super-fit kid. When I graduated high school, I think I was six feet tall; I weighed 210 pounds or something. I never lifted weights or anything like that then. And then you start maturing, and then get a little more fit.

JH You made a couple of stops in college before you got to pro ball.

PM I was recruited by Bobby Winkles, who was the baseball coach at Arizona State. And he offered me a full ride, and so I signed and went. My roommate lived up the road from me about 40 miles in this little town, and Winkles met with me and with him separately and said, “you guys are going to be roommates, because you live close to each other, and come up here to school.”

And then after my freshman year, Winkles left, and then this new guy [Jim Brock] came to ASU and he just basically told me he needed my scholarship, and he wanted me to leave — that I wasn’t going to play for him.

I said, “I can pitch if I can’t play [a position].” He said “no, I’ve got enough pitchers on scholarship.” I didn’t know at the time he couldn’t take my scholarship away, because I didn’t violate any rules or do anything wrong. But he wanted to bring his own guys in, and he figured he could tell me I wasn’t gonna play, then maybe I’d just leave.

So I sat out of school and worked for a year. Then a buddy of mine was over there in California, at a little school called Azusa Pacific. They happened to be in Tucson, playing the University of Arizona. I went to see him, and he said, “well, what are you doing?” I said, “I’m sitting out.” They used to have that winter draft in January. And so I said, “I’m sitting out for the draft; maybe I’ll get a chance.” And he said, “well ,if you don’t — ” he talked to the Azusa coaches.

In a small school, if you can pitch and play, if you can do more than one thing, you become kind of valuable on a team. But any kind of a scholarship situation, it kind of saves them money.

And so they talked to a coach at the University of Arizona, Jim Wayne, who was a big believer in Bobby Winkles. He said, “if he wants to come play, go get him. He’ll come play for you, and he’ll do a great job.” So sight unseen, they offered me a scholarship to come to school over there.

Paul’s decision to wait for the January 1974 draft ended up being a disappointment; he was drafted by the Cleveland Indians in the fifth round, but things didn’t work out.

PM I sat out for the draft, and the Indians drafted me:

“We want you to sign.”

And I said, “How much are you offering?”

They go, “Oh, a contract.”

I said, “Really?

“I’m working construction. I got to take off to get in shape and get ready for spring training. And I need income.”

“How much are you making a month?”

“About $500.”

He said, “We’ll give you $500.”

And then I had the scholarship thing, and the chance to go back to play ball in college, because I had two years’ eligibility left. I thought, well, damn, that’s — $500 just didn’t sound like a really good deal at the time. Again, being married — I was 18, just turning 19 when we got married – and so I just said, “I’m gonna go back to school.”

And when we went over there and just had a tremendous year; things went really well. It was great, because in Arizona you never saw scouts — hardly ever, anyway. Over there, they drive by and people are practicing and working out, because in Southern California, it’s just a hotbed for everybody.

This time, the strategy paid off; the Reds selected Paul in the third round of the 1975 draft.

JH So you stuck it out, went to Azusa, had a good year and then got drafted, and took off from there?

PM The Reds really thought I had a chance to do something, more than pretty much anybody else. And then that’s when they drafted me in 1975, and then it was off to the races.

Got drafted in the third round. I think Frank Pastore was the second pick. I was the third. Tony Moretto was the first pick. He was an outfielder from Indiana, I think. Then me, and then Scott Brown from Louisiana – we were the first four.

Scott threw a hard, heavy sinker. And he didn’t have a high-school baseball team. He only had like a sheriff’s league or something he played in.

JH He was a javelin thrower or something?

PM Probably, yeah. I mean, he could throw the crap out of the ball.

Scott Brown eventually made the Reds as a relief pitcher, and then pitched for Kansas City before arm injuries ended his career early. He is beloved by his teammates, and he has a heart of gold. But to say he was a “raw talent” early on was an understatement:

Scott and I were pitching side-by-side on the mounds in Billings; we’re warming up together and we’re throwing, and I call to the catcher, “fastball.” Then I go, “curve ball!” And he’s standing next to me, and he watches. And I had a pretty damn good curve ball.

So I throw it, and he’s looking at me, and I got the ball back and I wasn’t paying much attention. I threw it again, and I looked over.

I said, “What’s up?”

“What was that?

“It’s a curve ball.”

He said, “I’ve got to get me one of them!”

I thought that was the funniest damn thing I ever heard in my life. You just give him a baseball, and he just threw it. And he threw it really hard, and it was one of those heavy balls — those heavy, sinking kind of fastballs.

JH Hurt your hand, if you’re the catcher.

PM Yeah! Yeah. He could throw, but I didn’t get to play with him. Then he got to the big leagues, but —

JH He blew his arm out, and that was it.

PM Yeah, that’s kind of a common theme. That’s what happened to me. You know, back in the day, those were nasty surgeries to get over.

I mean, it was a quick way to get to the big leagues, but it’s a quick way out, boy, if you hurt yourself or get hurt.

1977: THE CALL TO THE BIG LEAGUES

Even as a Reds fan living in Texas during the 1970s, I heard plenty of games on WLW, the 50,000-watt “Voice of the Reds.” And I heard about Paul, Pat Zachry, Mario Soto, and others who were to be the “next wave” of young Reds pitchers. Paul was often praised as he came through the minors for his arsenal of pitches, as well as his bat.

JH When you were coming through the minors, I remember there was a lot of pub about you, and there was “This guy’s coming. He’s got the full repertoire; he’s really good. And he can hit.” A fair assessment?

PM I could hit! My first hit in the big leagues was a home run.

JH Right — your first game.

PM I struck out and then hit a home run, and then that went to my head. So I only hit one more the rest of my career. [laughs]

JH I did notice there were two of them!

PM I did pinch-hit some, though. Sparky would pinch-hit me on occasion, and I got a couple of pinch-hits. So yeah, I feel pretty good about that.

JH But you were always presented as “this guy is a fully-developed pitcher. He’s got plenty of pitches to get you out on. He’s coming through the farm system. He’s going to be a big thing.”

June 15, 1977 was a big day for Paul and the Reds franchise, because the Reds made several transactions that opened spots on the big-league pitching staff – including former Mets ace Tom Seaver.

JH You were called up right after the Seaver deal. Right?

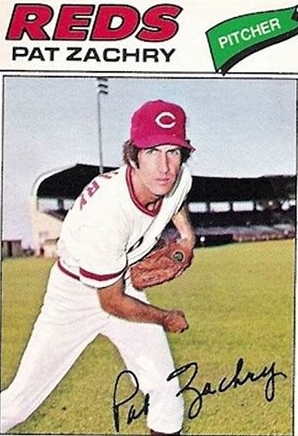

PM I was called up the same day. I mean, they called me up when they got Tom, because they lost Pat Zachry and Gary Nolan, and Steve Henderson and Dan Norman were two of my buddies from the minors — outfielders. Doug Flynn, maybe – was he a part of that?

JH Flynn was part of it. Flynn, Norman, Henderson, Zachry. I think that was it for Seaver, right? In New York they called it The Midnight Massacre. But they got rid of Rawly Eastwick about the same time, and all that stuff.

Seaver pitched well for the Reds in 1977, but the trade of Tony Pérez in December 1976 marked the beginning of the end for the Big Red Machine. The team Paul joined in June 1977 finished a distant second to the Dodgers.

PM I had heard many years after that — maybe I was talking to Bench or somebody — but they said that Sparky would come to Bench, Rose, Morgan, and Pérez if they were thinking about trading for somebody. Sparky would get input from those guys about what they thought about “would they fit in with our ballclub?” type thing. I mean, that’s the relationship those four guys had with Sparky, which I thought was just unbelievable.

JH I’ve seen a couple of interviews with Bench where he said the Reds either made trades or didn’t make trades based on what those guys’ input was — whether or not the guy would work. And there were some pretty big names, apparently, who did not come because those guys said, “No, that’s not gonna work.”

PM They were not going to fit with the ball club. Okay, so you got four Hall-of-Famers. I mean, who are you going to? Who are you going to trust about — what do they know about who these guys are? Because the players know about players, off the field and other stuff. And know how they would fit, and know what other people think. That’s, that’s pretty damned impressive that [Sparky Anderson] would relinquish something like that. Trust your guys.

They just gutted that 1976 team. I get called up; Tom comes. Of course, he stole all my thunder! [laughs]

It was, Paul who? [more laughter]

Actually, Paul was a big fan of Seaver, going back to high-school days:

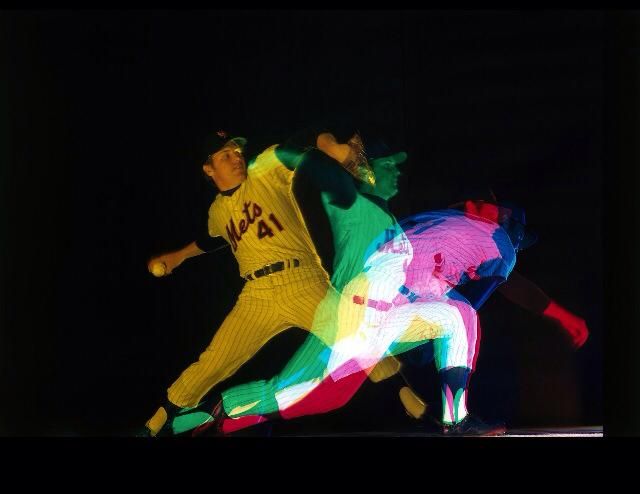

Sports Illustrated had done something, I guess it was like 1969, maybe. They did a sequence of Tom Seaver in his motion — different parts of it, like seven or eight pictures. Left leg up, left leg down, bending, knee dragging, all this kind of stuff. My high-school coach saw it, and he gave it to me and said, “if you want to learn how to pitch with the perfect mechanics, and you want to know how you’re supposed to do it, put this up above your bed and look at that every night.”

sequence of Tom Seaver in his motion — different parts of it, like seven or eight pictures. Left leg up, left leg down, bending, knee dragging, all this kind of stuff. My high-school coach saw it, and he gave it to me and said, “if you want to learn how to pitch with the perfect mechanics, and you want to know how you’re supposed to do it, put this up above your bed and look at that every night.”

So I put these pictures up above my bed, and it’s Tom Seaver. And I would get tennis balls and I would try to do what he did; I would throw these tennis balls into pillows I had set up on my bed.

So all of a sudden now there’s this [trade], and that’s the first thing I flashed back to. They said, “Tom Seaver’s coming, and you’re joining him.”

And I said, “Oh my God, that’s that guy! I mean, that’s Tom Seaver I’m going to play with!”

I’d been in spring training with the other guys, so I kind of knew them a little bit. But now, here’s Tom Seaver. And I was just like a kid in a candy store. I didn’t know how to react. I didn’t know how to handle things, I don’t think. I got kinda caught up in the whole big-league experience.

JH Really? So the king of drop-and-drive was there for you?

PM Oh, my God! I mean it was there, and then the next thing you know, he’s my teammate and now he’s talking to me? And we’ve stayed in touch over the years.

I would call him on his birthday. We’d talk, and he did some awfully nice things for me.

He invited me to go with him when he worked at the World Series for NBC for two years. I got to go tag along and kind of be a gopher type of thing, and get to experience that.

He took me to go see Camelot. I’m a kid from Tucson. My dad’s a school teacher. What do I know from that? And he got us seats, and he’d take me to art galleries.

Tom and Bench tried to teach me how to play bridge with some other guys, but I just — too much ADD, I think. I was so bad. Because in bridge you have that dummy hand that you have to lay down, and expose it. Well, I was the other dummy!

That bridge thing was beyond me, but that’s what they loved to play, and Tom and Bench were pretty good at it. And they tried to teach us. I was so bad at it that they would know what I was trying to bid, even though I wasn’t bidding correctly, just because they knew I just didn’t have a clue what I was trying to do.

JH Well, they probably wanted you to play with them, because you were their mark.

PM Well, I wasn’t — we weren’t playing for money — that was one thing: we wouldn’t play for money. Like, I never played poker. I told people, I said, why’d you play poker? The guys always played poker on the plane. You don’t want to play for a whole hell of a lot of money or anything. And I said, “If I’m going to play poker, I just need to hand it over and just dole it out equally to everybody sitting at the table, and leave. I’ll just sit back and watch you play. Here’s my money, take it.”

LEARNING THE BIG LEAGUES AND DEALING WITH INJURIES

JH You were talking before about how you think you kind of got caught up in the whole big-league thing. It really was that way?

PM Yeah. I knew when I got the ball in the minor leagues, I would expect to go out there and pitch, and finish the game. And I got to the big leagues and I think probably I struggled for the first time. Now, what do I have to do?

And then I was in and out of the rotation, and that was because of how I was pitching. I would be like the fifth starter. So you know, when you had off-days, Seaver would make his starts — all the first two, three guys would always go every so often, right?

And I would go in the bullpen and pitch in middle relief, and then Sparky told me that I needed to learn another pitch other than the curve ball, because I had a fastball, curve ball, and changeup when I got up there. So Bench and Seaver took me out in the outfield and taught me how to throw a slider.

If Bench would have pitched in the big leagues, he would have won 20, easy. Oh my God, he had such great stuff!

JH He said he was something like 75-3 as an amateur pitcher.

PM I’m telling ya, he could throw! It’s embarrassing when the catcher throws the ball back at you harder than you throw it to the plate, if he gets upset!

JH I heard the opposite end of that, when it was Jim Maloney or somebody in spring training, and Bench said, “you’ve got nothing on your fastball.” And he caught it barehanded.

PM Yup. I asked Bench about that. I said, “okay, I’ve heard this old wives’ tale thing. I’ve heard this urban legend, and tell me, really.”

He said, “No, no, no. I kept putting down the curve ball, and he shook his head. He wanted to throw a fastball. I put a curve ball down, he’d shake his head.” John said, “I even pointed to the dugout, and he said ‘no, I want to throw the fastball.’ I said, ‘go ahead.’ He threw it, and I just reached out and caught it barehanded.”

I said, “you really did?”

I tell you, you knew you were in trouble when you’re pitching to Bench, and you’re looking in at him and he’s looking over the dugout at Sparky and he shakes his head like, “Nope. Sorry. He ain’t got it!”

JH That was supposedly what he said to Sparky just before Fisk hit the home run off Darcy [to end Game 6 of the 1975 World Series]. He looked at the dugout after Darcy warmed up and said, “No chance!” And then, pow!

PM A little slider. Hey, but at least he got a chance to throw it in the World Series. You know what I mean?

JH A regret of yours that you never got that — ?

It’s a regret of anybody who never got there. Right?

In 1976, I was in AA. I’m 13-6 or 13-7, whatever the hell it was. I’m just pitching my butt off, and I’m throwing really well. And the Reds were getting in the playoffs, and I thought, “Well, it’s getting to be time to call guys up.” And I told the pitching coach — the traveling pitching coach — I said, “maybe they oughta call me up. You think maybe I have a chance?”

He goes, “Nope.”

“Why not?”

“Well, you’re not on the 40-man roster, and to clear a space they’d have to take somebody off” — and then it was explained to me how all that crap worked. You take somebody off, put somebody on, or whatever.

And there was always a fear back then, I guess, of people getting up there too quickly.

JH Pat Zachry was another guy who put up some good numbers for quite a while,  and he took a while to get to the big leagues. It’s not like he didn’t have the credentials. If you looked at those numbers today, both of you guys would have been up there faster.

and he took a while to get to the big leagues. It’s not like he didn’t have the credentials. If you looked at those numbers today, both of you guys would have been up there faster.

PM I doubt that I would have finished the AA season, probably, doing that well and winning that many.

JH And you’re 13-6, 1.55 ERA. You would’ve at least gotten a September callup.

PM Yeah. Rick Sutcliffe was in the league that year in AA, and André Dawson was there. Plus the guys on our team. But yeah, that’s an awfully competitive level, AA.

JH Wasn’t the thought then that AA was kind of the make-or-break point for a lot of guys? That if you could go past AA — if you succeeded in AA, you could possibly make it all the way?

PM Yeah. And they liked keeping the guys doing well, playing together in AA, the younger guys and stuff. Because AAA was — back then it was guys who had been in the big leagues, kind of hanging on. Maybe they might need somebody if somebody gets injured at the big-league level. So you’ve got guys who are on their way out, their careers were probably winding down — how they could influence younger guys, and all that kind of stuff.

So I think they wanted to keep their prospects in AA, and then they moved us en masse to AAA after the next year. In ’77 we all went. We were in AAA together.

JH I have team photos of some of mid-Seventies Indianapolis clubs, and you look at the percentage of guys who made the big leagues out of there, it’s three-quarters of the roster!

PM That’s pretty remarkable, I think. I think that just speaks to the Reds and Mr. Howsam, and how they ran that whole system. Minor-league pitching coach was Scott Breeden, who pitched in the big leagues, and who was a calming influence on a lot of us. I mean, they just did it right, and you earned your way. They just did a really fine job with that.

I think you held your head higher for being a Reds player. You really had something you had to live up to after 1975 and 1976. They got the Kluszewskis; you got Marty Brennaman and Joe Nuxhall in the radio booth. I mean, you get all these just wonderful human beings all over the place, and a great organization, and how they went about doing what they did to develop talent, and everything that they did.

Of course, they didn’t pay anybody any damn money, but yeah, but nobody’s ever satisfied. [laughs]

JH You were saying that even though you were up in 1977-78-79, you were still trying to sort of figure out the big leagues on the fly?

PM I got there, and it was just — I just needed to have stepped my game up more than I did. I think just focus-wise and everything else. And my arm started hurting, and then I ended up tearing up my arm.

JH What was the genesis of the arm problem? Is there anything in particular that you can point to?

PM No, I just know that I had seen some chest X-rays after it was kind of diagnosed, that it showed a bone spur developing on my right collarbone and my right shoulder. The pain just got worse, and I was taking prescription medication to kind of numb the pain, and that kind of stuff. And it just didn’t seem to work.

It got to be the point where it was just so hard to just physically go out there and do it. And so I requested to see Dr. Jobe, and he’s the one who told me that there was no joint space; that I had worn it all out. There was a bone spur, and he felt the only thing that he could do at the time was to take off some of my collarbone.

I guess I was one of the only pitchers back then who had that operation; I’m not sure. But it just — that was kind of “it.”

When I tore up my arm, I had an inch of my collarbone cut off. I had no AC joint space, apparently. And Dr. Jobe was the guy at the time. He just said, “well it looks like we got to create some space here.” And so they just lopped it off.

And then I went from [throwing] close to mid-90s to — I don’t think I threw the ball 80, 82 miles an hour or 84 miles an hour. And I couldn’t throw 40-50 pitches.

I was just starting to kind of get this thing figured out, pitching in the big leagues, and then that happened, and I’m like, “Oh, shit.” So I hung on as long as I could.

I don’t have any regrets about it. I mean, I did everything I thought I should do, healthwise and throwing-wise and stretching and working out in the offseason and all that.

It just could have been, I wasn’t born to be a pitcher, maybe.

JH Was that something that deteriorated over a period of years?

PM It just got worse. I wasn’t aware of it for the first couple of years, because really, before I signed, I hadn’t pitched a whole heck of a lot. I was working, then I was out of school for a year and I was working, and I wasn’t playing much baseball. Then I went back to school at an NAIA school. I didn’t pitch a whole heck of a lot; I played [other positions] as much as I pitched.

Then I get drafted, so I didn’t have a lot of pitches in my arm already. So I don’t know if it was accumulation. I don’t know if it’s bone — I don’t know any of that. I just know what ultimately happened.

JH At what point did it really get bad for you? I’m looking at your records here, and you made 25 starts in 1978. I mean, that’s a pretty full season.

PM Yeah!

JH Then in 1979 you were in AAA for a couple of starts. Was that like a rehab deal?

PM I think I wasn’t pitching well, and I got sent down, to kind of wake me up. [laughs]

JH You were 5-4 in 1979 with a 3.89; 15 starts, 21 appearances. And they actually sent you down for a couple of games? Was the arm heading south by that point?

PM Yes.

I think it kind of started showing up more in late 1978, or early 1979. I didn’t really know I had a problem. I just figured you were sore when you got done pitching — except the soreness didn’t dissipate as fast, and didn’t bounce back as fast.

So you’re taking medication, antiinflammatories, and Larry Starr in the training room, he’s working on you, stretching you, doing some weight stuff to try to build up more arm strength, and that type of thing.

But it was starting to get worse, and it just finally got so bad, I could hardly throw. And I couldn’t throw as hard.

JH Were you not on the postseason roster in 1979? You didn’t pitch in the playoffs in 1979?

PM No.

JH That was a disaster anyway, getting swept by the Pirates and all that stuff. What happened that you weren’t on the roster?

PM Was I on the DL? I might have been on the disabled list before that.

JH You had 15 starts, 21 games, 106 innings. But then —

PM I was pitching in middle relief and stuff, I guess. And I think that getting treatment as often as I did, maybe — because the trainers have to write reports. How are you feeling? How’s your arm? It just could have been all of that.

I don’t really have a strong recollection of actually what was going on with me then, with my arm. I just know that it started hurting, and I just couldn’t be as effective, and I ended up more in the bullpen. I was always that guy who was gonna be the fifth starter most of the time anyway, and middle relief or long relief or whatever they call it these days.

JH You were kind of taking the Fred Norman role there for a while [as a swing man].

PM Yes.

JH In 1980 you got 33 games, but only 19 starts, and then 1981, 27 games and only one start. And only 54 innings the whole year. So obviously, a change.

PM That was after surgery, because I had surgery in 1980, in the offseason.

JH Yeah, because you had 152 innings in 1980. That’s a reasonably full workload there. Especially with 33 appearances.

PM And then I had that surgery, and then they traded me after that, in 1982.

1982-1984: ORIOLES, PIRATES, CUBS

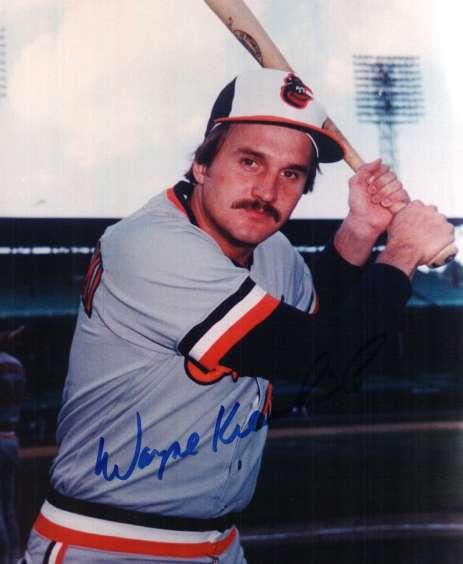

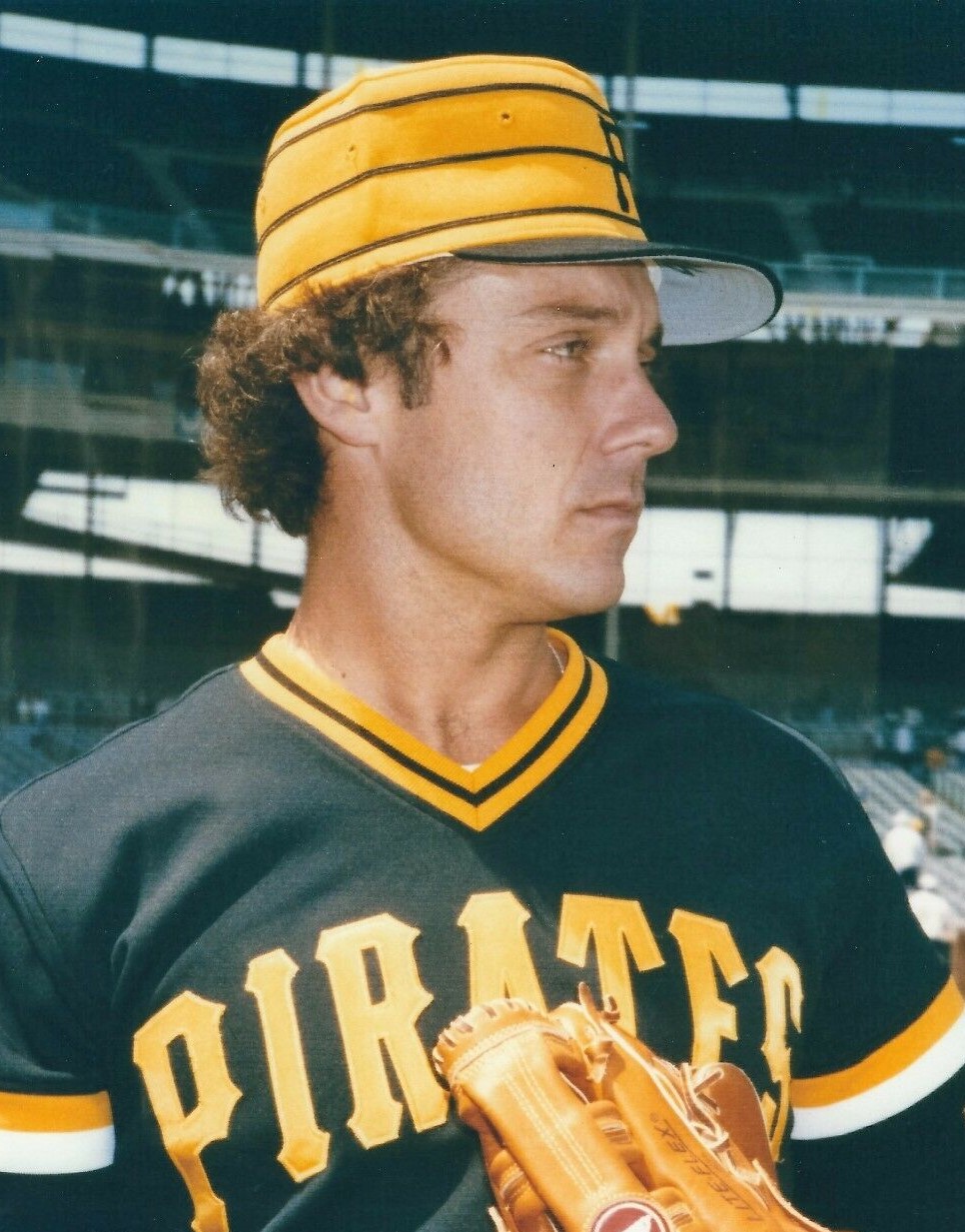

Paul was traded to Baltimore in February 1982 for a player to be named later. Ironically it was for Wayne Krenchicki — one of my best friends in baseball. But Paul was only with the Orioles for two or three weeks, then was put on waivers – and was claimed by the Pirates.

PM I don’t understand the trade. I don’t know why or whatever, but I went over there, and that was the year, I think Don Stanhouse and Ross Grimsley were talking about making a comeback. They had showed up there in spring training. I kind of saw the handwriting on the wall, because I don’t think I even hardly even pitched for them in spring training.

JH You were only there for two-and-a-half weeks.

PM After that surgery, I couldn’t throw anymore. It must’ve been pretty apparent to a lot of people. And then I was [with the Orioles], and then I called my agents, they released me, and I had already shipped my car up to Baltimore. My wife’s off in Arizona. I mean we are just scattered all over — the kids, everybody was gone.

JH Baltimore never really explained what the deal was, or why they would — it’s just weird to me that the Orioles give up on Krenchicki, who was a 1976 first-round pick, and they trade for you, a former third-round pick; and two weeks later you’re on waivers and get claimed by Pittsburgh? You never really got an explanation for what the hell the thinking was there?

PM No, I just chalked it off to those — with Grimsley and Stanhouse being there in spring training, I just figured, the only chance I’m going to make this ballclub is going to be a middle-relief guy. I’m not going to be a starter. I’m not going to be a closer. I’m going to try to keep my job.

I figured, they traded for me; there must be something there. But on the other hand, I’m wondering, why did they trade for me if they knew I just had arm surgery — that I had a surgery they probably most people hadn’t heard of at the time — and not knowing how I was going to come back from that?

JH It just doesn’t make any sense. I’ve never understood that. They make the trade —

PM Did they not have any need for Wayne over there, and they just figured, “well, if we can get anybody – well, hell, there’s a pitcher available. Let’s see if we can – see what the hell happens.” I don’t know.

JH Chicki told me that he just couldn’t break through, because they had guys like Kiko Garcia and Rich Dauer. And he couldn’t break through that. He bounced up and down between Rochester and Baltimore for three years. He said, “it was wasted time for me.”

PM Sure.

JH He was glad to come to Cincinnati, but the deal still just makes absolutely no sense to me. Somebody knew you were damaged goods, and they look at you in two weeks and say, “okay, we’re done with that”?

PM I do remember, vaguely, having a phone conversation with Ray Miller, who was the Orioles’ pitching coach:

“Welcome to the club, blah blah. How you feeling?”

“Great!”

“You’re working out?”

“Yeah, throwing”

You know, the same old shtick everybody always tells everybody.

And I got a good sense from him, and I was again excited about going. Jim Palmer was there, and that would be cool. And got there, and it just like — it was almost like they traded for me and then they didn’t have any use for me once I got there. Kinda how it seemed.

JH From just from a fan’s point of view, it’s “what the hell was that for?”

PM Whether it was both teams wanting to get rid of somebody and just, had ’em out there and figured “somebody will pick him up,” or “he’s got enough wins in the big leagues. Maybe people give will give him a shot. Yeah, he’s had surgery, but everything seems to be fine.” Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

JH It’s like they talk about that old “addition by subtraction” thing.

PM Yes. I think Cincinnati probably knew that was about it for me. Maybe I’d worn out my welcome there; I really don’t know. Maybe I wasn’t being successful like they ultimately had hoped, so they figured they could move me for anybody: “Let’s just find somebody out there that would take him.” And you know, maybe that just popped up. I don’t know the relationship between general managers, and who knew who on what side, and all that crap.

JH All the front-office politics.

PM Yeah.

So they called me and asked me if I would go over that day to throw for the Pirates. I got over there, and I thought I was going to pitch in a B game or something. They said, “can you go out and pitch a couple of innings?” And I went out and I thought, “well, here’s my one-and-only chance.” So I just kind of let it rip, as best I could.

got over there, and I thought I was going to pitch in a B game or something. They said, “can you go out and pitch a couple of innings?” And I went out and I thought, “well, here’s my one-and-only chance.” So I just kind of let it rip, as best I could.

And then they said, “well, can you give us one more inning?” I said, “oh, sure.”

Oh, shit, my arm was hanging. [laughs] So I go out and do the other inning.

JH Oh, no!

PM Well, I go out and pitch for them, three innings, and then the next thing you know, I’m breaking camp and heading north with the Pirates.

That was a fun year, but I didn’t pitch much; my arm was killing me. [He was 1-3, 4.37 in 13 games with Pittsburgh, and 0-4, 10.32 in AAA in 1982.]

JH So you did end up making the Pirates, where you were 1-3. And so I guess they figured, “well, we got something out of the guy.”

PM Yeah, I was done, pretty much.

Paul was released by the Pirates after the 1982 season, and he signed as a free agent with the Cubs in January 1983.

PM I was in Chicago and I got to go to spring training with them, and then I got called up when Dickie Noles had to go away for a month or so. I thought I did okay with them, but then they sent me down and released me. But I knew by then it was all over.

JH So in 1983, you didn’t make the Cubs out of spring training?

PM No.

JH You were in 11 games with Iowa, then eight with the Cubs, and got released August 8, 1983.

PM I got called up there, then Dickie Noles joined back with the club, and then they sent me back, and then I got released. I think I was in Denver when I got released. We were playing in Denver on the road.

I kind of knew it was over. I knew I just couldn’t throw anymore. My arm was killing me, and I was just trying to do my best and hang on, like anybody else.

It was time.

JH But was there a little bit of a feeling that if your body hadn’t failed you, there might’ve been a lot more there?

PM I believe that, because I think I showed that before I got there, and I had some bit of success with Cincinnati in the big leagues. And then my arm started bothering me, and everything kind of went down the hill; then after the surgery, that was kind of it.

But you know, I’m like a whole lot of other guys who have a career vision and then injury happens, something happens and, you know … [pause]

JH Any regrets?

PM No. The thing about it was, I always have [thoughts about baseball] in the springtime, when you smell cut grass, because it just takes you to spring training.

But the fact that I physically couldn’t do it, that’s why I was out of the game. I think that made that a little bit easier for me. Not that it was easy. I mean, 28, 29 years old. My career is over at 29? That’s quick.

LIFE AFTER BASEBALL

JH Was it tough to adjust after you got out of baseball?

PM Yes. I sat around and pouted for about a year. [laughs]

JH What then?

PM I got into some small business with some people. Got in the cellular business for a while.

I became a general manager of a AAA team, Tucson, for the Astros. I was living there and doing a little radio broadcasting and Pete, the guy who owned it, was from Canada. And he had five minor-league teams and his concept was, he wanted to put together an entire organization from rookie ball through AAA. But the big-league clubs, they just didn’t want that one person having that much control over that many teams in an organization.

But anyway, they’d asked me. They said, “well, you’re local; people know you; would you want to come do this?” I said, “I don’t really know much about working in the front office and doing that kind of thing.” And they said, “that’s okay, we’ll teach you.”

And I did that for five years.

JH Was that a big learning curve?

PM Basically, it was a sales job. It was kind of behind-the-screen thing. So it was different for me than as a player, cause I was always in front of the screen.

So you worry about how many people were showing up. What’s the promotion? Bathrooms clean? You hope all that stuff goes, and it’s just sales. It’s sales and promotion.

And I didn’t have any experience doing that, so I got to be real good friends with a guy named Bill Lee, who was the president of the Frontier League; has been for like 25 years now.

When I was general manager in Tucson for the AAA team, he was a general manager in AA for Chattanooga — for the Lookouts. And that was owned by the same people that I went to work for. So they basically had him kind of mentor me, and we got to be very close friends, and we still see each other.

JH But being a general manager in in the day you were doing it, was not so much about the player-personnel side as the functional workings of the ball club – that kind of thing?

PM Right. And there was a contract that was signed between the AAA team and the major-league club about what they’re going to supply: how many balls, bats, uniforms. We had to pay some for hotels, for flights. Oh, I’m trying to remember — the PDC. Player Development Contract.

JH It’s like a distant cousin to a Working Agreement, isn’t it?

PM Yes, absolutely. Basically you had no — you didn’t have any input on anything about [the roster]. Nor did they want it, because they had their own personnel, their own field staff that they’re paying.

So it was just a sales job, in sales and marketing, is what that was about. The city ran the ballpark. They’d put the concessions in; we sold billboards; we sold season tickets; we did promotions and concerts and all that stuff, to try to get people to come out to the ballpark. And so that’s what I was thrown into.

JH Is that tough to do when you don’t have any say about the roster — when you’re promoting players who you don’t really have voice in whether they’re there or not? You’re on the other side of the screen, as you say?

PM No, I don’t think so. I saw things, I saw kids and sometimes kids would ask me, they say, “you’re a pitching coach” where they just wanted a different set of eyes, and somebody said, “Hey, Paul, would could you come out if I get in tonight, in relief or something, and see if you see anything, or pick up anything” And they [would] come talk to me privately. It wasn’t something that – people didn’t really know that much about.

But I was just there and available if somebody wanted to talk about something, because sometimes you need somebody who’s not with the organization; who has a different input.

JH A little detached perspective?

PM I think so. But I got along great with them. I was just trying to figure out what the hell I was doing. I mean, that was an obligation. These people were paying me money to do this job, and I tried to do the best I can to do the job right.

JH How did that end up? You did that for a few years. What happened?

PM After five years, they sold the ballclubs; they sold the AA club. Bill Lee went and became the commissioner of the Frontier League when they got going, and he’s been there ever since. And the same guy who bought the AAA team, bought the AA team. And so he made a change.

He sent somebody out to be my “assistant.” And then once the check cleared, he said, “this is my guy.” And I had told myself and told my guys, “if anybody’s gonna get fired, it’s gonna be me.” Because I was working for the guys who were here before. “So you guys gotta do your jobs; keep staying out there and keep selling, and then somebody’s going to go. It’ll probably be me.”

So it was me. That’s business. I mean, nothing personal.

JH No, but still — I think the technical term is, that sucks. [laughter]

PM It’s like working for a ballclub, and somebody trades you; you don’t have any say in it. You’re gone. You know, if I own it — if I’m going to have a business — I’m going to want people around me I know; not somebody who worked for the other guy.

JH And speaking of not having any say, did the Reds ever give you any explanation for why they traded you?

PM No. Not that I remember.

JH They just said, “see ya,” and that’s it?

PM Well, I remember one time I got sent down from the big leagues, I came in [to the clubhouse] after a game, and I wasn’t pitching. And the writers came up and started asking me about, “how do you feel?” I said, “what are you talking about?” “Well, they just sent you down.”

JH And that’s who you heard about it from?

PM Oh yeah. And they went, “Oh, we thought you knew!” “No, but thanks!” [laughs]

JH Stay classy! What happened after the general-manager gig?

PM Then I was in the cellular business for a while. A partner in a business. And one of the guys retired; my wife and I got involved in that. And then a friend of ours, where our kids grew up; my son played baseball with his son. He ran a coed high-school boarding school in Tucson [Fenster School of Southern Arizona] that had been around since the Forties.

He was the headmaster, and he needed some help staffing-wise, and he wanted me to come and be the dean of students and athletic director for him. He said, “I know you’re good around kids. Come over and see.” And I went over there, and I was there 18 years.

JH Pretty nice job.

It was great, because kids keep you on your toes. That’s the one thing about it. The kids we had were off-track; didn’t care much about school, getting in trouble, substance abuse a bit, and stuff. Trouble with the law, just not getting along with their parents. Didn’t have a direction.

And so we had a boarding school for boys and girls. So it was interesting. They keep you current; you’re trying to figure them out. You’re trying to make sure that they’re not — we could drug test and have breathalyzer — we had to have security people, because they lived there. It was 150 acres, northeast Tucson, out away from town a little bit.

So I did that for 18 years, and then after the school started kind of dwindling away and stuff, that was it. And I retired, and I’m done. I was done — done working.

JH Do you keep your hand in the game at all anymore? How is life for you now?

PM No. We’re retired. We live in a lovely community up here. We have a lot of nice friends. We’re traveling now; we didn’t get to do much of that before. We’ve got three grandkids in Georgia. We have one grandchild out here in Phoenix. We see our grandchild here once a week. And we’re just, get up and walk, exercise, and go out to dinners. Joined the wine club. And I never knew I would live in a retirement community, but I am. And I never knew I would move from a place hotter than Tucson, but we did. God, it’s hot up here!

We just want to get out of here in the summer to go visit people, and try to be gone as much as we can. My sister lives outside Albuquerque at 7,200 feet, so that’s an easy one.

But it was a good career. You know, what the hell; look, I got to play in the big leagues. I can’t complain.

Thanks to Paul for a wonderful interview. In Part 2, Paul and I talk old-school baseball and some issues we have with today’s game.