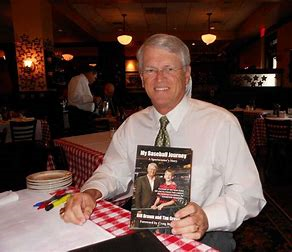

“I’m just blessed,” says the longtime Reds and Astros broadcaster

Bill Brown had a long and successful run with the Cincinna ti Reds and the Houston Astros. The road to the big leagues was just as full of trials and tribulations as any player, however. His faith, desire, some great broadcast partners and mentors, and an understanding wife helped him navigate the sometimes-rocky road to the big leagues.

ti Reds and the Houston Astros. The road to the big leagues was just as full of trials and tribulations as any player, however. His faith, desire, some great broadcast partners and mentors, and an understanding wife helped him navigate the sometimes-rocky road to the big leagues.

The Missouri native began his play-by-play career covering Jefferson City High School football and Lincoln University basketball on radio station KWOS while he was an undergraduate at the University of Missouri. He eventually landed an internship at station WOAI-TV in San Antonio prior to his senior year. After graduating from Missouri in 1969, the newly-married Brown was hired by WOAI as a news photographer, though his long-range goal was to work in TV sports.

But this was at the height of the Vietnam War, and in 1970 Brown was drafted. In 1971 he was stationed in Long Binh, Vietnam. “I thanked God for keeping me on the periphery of harm’s way,” he wrote in My Baseball Journey.

“I came to think of war like a tsunami: Individuals are powerless against its current, and with its strong tide comes massive anguish, devastation, and loss of life.” — Bill Brown, on his experience in Vietnam

He was later transferred to a position with the American Forces Vietnam Network (AFVN) to cover sports. “The Army gave me my first big career break,” he said.

Brown was discharged in November 1971, and by law, WOAI was required to offer him the job he had before he entered service.

“But my wife did not want to go back there,” Brown said. WOAI was part of Avco Broadcasting, and so while Brown entered graduate school at Central Missouri State, he was kept apprised of openings at other Avco stations.

Brown applied for positions in Dayton, Ohio and Cincinnati, and eventually landed a position in March 1972 with Channel 5 in Cincinnati. He was a weekday booth announcer and weekend sports anchor at WLW radio and WLW-T TV.

His boss at WLW was Phil Samp, who was best known for his long tenure as the original radio voice of the Cincinnati Bengals.

“I tried to absorb everything I could from Phil,” Brown said.

One of the things Brown picked up from Samp was the first thing I noticed about him on air: he placed a stopwatch next to him so he could stay “on time” during each sportscast.

Brown laughed when I asked him if he was self-conscious about the watch being “in frame” (visible) during the broadcast.

“No,” he said. “I figured that if Phil did it, it must be OK. I had, say, six minutes of air time, and I knew exactly how much time we had for each story. I didn’t want to ‘lose’ any stories.”

When he wasn’t on air live, Brown’s bosses had plans for the newcomer to the Cincinnati market.

“We want you to be out in the community – get immersed in things,” they told him. One of the things Brown did was to take a tape recorder to Riverfront Stadium, find an empty broadcasting booth, and record himself calling game action.

“It was a really effective tool to improve,” he told me. “I thought, ‘I don’t have the minor-league experience that these guys have – the know the game so much better. I need to work on my skills.’”

Another part of Brown’s “immersion” was hosting a 30-minute baseball pregame show called Redscene.

“I was sort of second in the pecking order in the sports department, and Phil Samp was at WIlmington [Bengals training camp] all summer, so he did not do TV sports. It really gave me a lot of work.

“I needed the airtime. Needed to increase my knowledge base,” he said.

I asked Brown about the Reds’ involvement with the program. Did they have input or control over the content, as so many teams do?

“It was all Channel 5, but the ballclub knew about it,” he related. “They were sold out [in terms of ads] on the games – the ratings were really good – and they wanted another avenue to make more money. So they thought, ‘we can do an adjacency here with Redscene and put it on a half-hour before the game. Maybe fifteen shows a year.’ I was out there all the time, and it helped me to learn the club better.”

Brown found an ally in Reds manager Sparky Anderson, who was surprisingly media-savvy:

“Sparky was tremendous,” Brown said. “He even did a segment on Redscene five minutes before the game — live on the field. He had a great clock in his head, and he was perfect for a three-minute interview. He knew exactly what the broadcast wanted.”

Late in the 1972 season, the Reds broadcasting rookie got the surprise of his life when he was asked to fill in on a broadcast from Houston as the Reds were closing in on a division title.

Brown thought he was going to broadcast a weekend game as color man, with play-by-play man Tom Hedrick. But when the Reds had a chance to capture the division title, a decision to broadcast the potential clincher was made late in the afternoon of that evening’s game.

Brown was even more surprised when, with the Reds leading late in the game, Hedrick left the booth to cover the locker-room celebration if the Reds won.

“Who’s going to do the ninth inning?” Brown asked Hedrick.

“You are!” said Hedrick as he left.

Shocked, Brown did his best to get by – although he remembers little of his debut.

“I was numb. I had no warning. I was totally unprepared. It was my first year there. It was just so crazy.” — Brown, about his Reds play-by-play debut in 1972

Of course, Brown didn’t get a 1-2-3 inning. Usually-reliable closer Clay Carroll walked the bases loaded before Cesar Cedeño grounded to Darrel Chaney at shortstop to end it and clinch the title.

“I have no idea how I did,” Brown said. “I was just trying not to screw up.”

For the next few seasons, Brown filled in on Reds TV broadcasts for Woody Woodward, and, later, Charlie Jones. Jones was an “import” – a nationally known football voice, among other sports – but it was not an ideal arrangement for the broadcasters or the fans.

“Charlie Jones was from La Jolla, California,” Brown said. “He did not know baseball. He was tremendous in other sports, but not baseball. He was hired because of his name, and his voice. He would do NFL in September and they would need a fill-in.

“I was the next guy in line, and I thought, ‘maybe I will get this job some day.’”

When Jones’ contract expired, the Reds turned to veteran Ken Coleman for play-by-play duties. Brown was promoted to the analyst/color-man role – one for which he was outside his comfort zone.

“That was foreign to me,” he said. “Ken was so nice, but I didn’t have the skills to be a color guy. It was a break for me when he went back to Boston and I got to do play-by-play.

“I was no Tony Kubek,” Brown said, referring to the ex-Yankees shortstop who was NBC’s Game of the Week analyst for many years. “It’s a feeling of inadequacy – and I think deservedly so.”

So acute was this feeling that Brown would often go to the field during batting practice and ask players a few questions, then drop in their responses where he felt it was appropriate to make a point during the broadcasts.

I asked Brown about his preference for the 1975 Reds – who won 115 games and defeated the Red Sox in a memorable World Series – over the 1976 team that won 102 games and swept the Phillies and Yankees to repeat as world champions.

“I just thought they had everything. And it’s harder to win that first one,” he said. “Winning in 1975 gave them a big assist in 1976.”

“I remember thinking: ‘This is so unusual – moving Pete [Rose to third base] in midseason.’ I thought they did such a good job changing on the fly. Then they were pressed to a seventh game in the World Series before they won it.”

And at the end of Game 7 in 1975, Sparky Anderson “played a hunch,” Brown wrote, and brought in left-hander Will McEnaney to close the game, instead of right-hander Rawly Eastwick, who was the main closer at that point.

Why use McEnaney? Was it because Eastwick had given up the game-tying home run to Bernie Carbo in Game 6?

“Sparky just had such a good feel for how to use his pitchers – what was a good matchup and what was a bad matchup,” Brown said. “And he was blessed to have two guys who could close in Eastwick and McEnaney. I don’t know that you would see that today.”

“He was phenomenal in his feel. I think the best managers are.”

I lived in Texas during most of the Big Red Machine years, and saw them play many times against Houston, who always gave the Reds all they could handle. Did Brown see it the way I remembered?

“Yes, and I thought it was so dark in the Astrodome, and the ball didn’t carry, so I thought it nullified some of the Reds’ power,” Brown said. “And with Joe Niekro, Nolan Ryan, and J.R. Richard, how are you going to win that series?”

I recalled the devastating effect of Richard’s slider, which could make even the best hitters look foolish. “Johnny Bench often got a night of rest when Richard pitched,” laughed Brown.

And speaking of the Big Red Machine …

It was often suggested that there was real rivalry between Pete Rose and Johnny Bench during the Big Red Machine years. Joe Morgan has said that when he came to Cincinnati in 1972, he was told he could be friends with Rose or Bench, but not both.

Truth, or exaggeration?

“There was something there,” Brown recalled, “but Sparky kept it together. It all worked because of Sparky. [On the player side] Tony Pérez was the guy who made it all happen. He kept everybody level.

“It all worked on the field, and that was the important thing.”

The trade of Pérez to Montreal after the 1976 season is often pointed to as the beginning of the end of the Big Red Machine. Not only were the players obtained in the trade — pitchers Woodie Fryman and Dale Murray – busts in Cincinnati, a vital clubhouse presence was gone.

“I didn’t realize it at the time, because I bought into Dan Driessen being ready,” Brown said. Indeed, Pérez hit .283 that season, with 19 HR and 91 RBI; Driessen hit .300 with 17 HR and 91 RBI. But things were clearly not the same with the Reds, who finished 10 games behind the Dodgers.

“It had everything to do with the clubhouse mix; there was a huge void,” — Bill Brown, on the 1977 Reds

Brown became the number-one play-by-play man for the Reds in 1979, and he held that post until he was fired following the Reds’ disastrous 1982 season, when the team lost 100 games for the only time in its existence.

Brown got the classic “we’re going in another direction” notice. He didn’t see it coming, although he had a contract where he could be let go at the end of each 13-week period.

“They had perfect legal protection, and I didn’t do a very good job,” he says now.

“I was trying to be Ray Scott instead of me,” he said. Scott was known for his economy of words during a broadcast.

“I thought, ‘I don’t have to talk a lot; Cincinnati fans know the game,’” he said. “I clammed up, and it didn’t work.

“I tried to put more energy into the broadcast. Instead, I sucked energy out.” — Brown, on the 1982 Reds

He’s pragmatic about his termination.

“I was devastated, but now I can look back and identify these things and see it was justified,” Brown said. “It was a very beneficial process for me to be fired.”

Brown eventually landed jobs in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles before a chance meeting with Dick Wagner, the Astros’ general manager who was with the Reds when Brown worked in Cincinnati. Wagner encouraged him to apply for an open position on the Astros’ broadcast team.

Thus began a 30-year relationship between “Brownie” and the  Houston club. Brown was determined to learn from his Cincinnati experience.

Houston club. Brown was determined to learn from his Cincinnati experience.

“When I got to Houston, I said, ‘that is not going to happen again. I’m going to get more energy into the broadcast.’ That was the ultimate lesson I learned from getting fired that helped me later on.”

Brown is grateful for his Astros broadcasting partners. They showed him another side to the business of broadcasting.

“On television, it’s a team,” Brown stressed.

“When JD [Jim Deshaies] and I were paired together, that was the best — because he was a great entertainer. The objective becomes for the team to work, and the team worked better with less of me.

“I still had to do the play-by-play, which was plenty enough – that’s a big job, and that’s all I wanted. The fact that he was able to provide such entertainment was a terrific bonus. It was on me to let him entertain.

“That’s easy: just shut up!” he said, laughing.

“[Deshaies] just had this innate ability to entertain. In a one-sided game, the switch would flip and he would talk about other things.

“That was not in my nature at all.

“He loosened me up; I was always too serious, and I was too intimidated by the Vin Scullys and Jack Bucks of the world. JD taught me the value of entertainment.” — Brown, on Astros broadcast partner Jim Deshaies

“The ‘sales’ part of the job did not come naturally to me,” Brown said. “Being from a journalism background, that really had not been instilled in me.

“Reading promos is one thing; I learned a lot from Larry Dierker about how do that. Larry had been in ticket sales before he became a broadcaster. He knew how to work a sales plug into a broadcast without making it sound like a sales plug.”

Not that making these adjustments to his style was always easy – albeit necessary.

“I was kicking and screaming to the end about doing these things, but that’s the world we live in today.”

But Brown broadcast 30 years with the Astros. So was Houston simply a better fit?

“If I had stayed in Cincinnati, there’s no way it would have worked out as well,” he said. “Anyone who does TV there is going to be in Marty Brennaman’s shadow. And Marty’s a good guy.” (Brennaman has been the radio play-by-play voice of the Reds since 1974.)

“It was a different shot,” he notes. “I said to myself, ‘I’m just going to do this, and do a better job.’ I think I would have become too comfortable in Cincinnati after X number of years. And I think eventually they would have gotten rid of me anyway.”

“I think God was watching out for me, but it was helpful to go through the trials and tribulations and moving around the country to make me understand when I got the Astros job how much I needed to appreciate it.”

“I just felt I was blessed to be doing major-league baseball,” he said. “I knew I wasn’t Marty Brennaman or Al Michaels or Jack Buck – they are truly Hall of Fame guys.

“I had done what I could do. I had certain abilities and some limitations, and I worked with some great partners who gave me perspective and direction and understanding.”

Brown retired from full-time broadcasting at the end of the 2016 season. Again, he has a solid perspective about his time in Texas.

“I’m just really fortunate that I was able to come here to Houston and meet so many good people and have so many good partners. It’s a nice, comfortable home for us, so as a total experience, I’m just blessed. That’s what I come away with.”