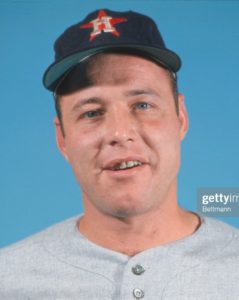

Jim Haught: Normally this section is a read-only thing, but today we have a special opportunity to present a podcast with Larry Dierker: former Astros pitcher, manager, and broadcaster. Larry pitched a no-hitter for Houston in 1976, but in September, 1969, he pitched what he felt was an even better game, though he lost a possible no-hitter with two out in the ninth inning.

opportunity to present a podcast with Larry Dierker: former Astros pitcher, manager, and broadcaster. Larry pitched a no-hitter for Houston in 1976, but in September, 1969, he pitched what he felt was an even better game, though he lost a possible no-hitter with two out in the ninth inning.

We’ll talk about that game and its significance to Larry, and the Houston Astros franchise. Larry, welcome aboard.

Larry Dierker: Thanks, Jim.

Jim: Let’s set the scene a little bit. In 1969 the Astros started 4-20, and the 20th loss was a no-hitter by the Reds’ Jim Maloney. So Don Wilson returned fire for the Astros the next night, and his no-hitter seemed to be the spark that sort of turned your season around. Is that a fair statement?

Larry: Yes, it’s accurate. I think we won 10 games in a row after that, and had another 10- game winning streak later in the year.

Jim: Yes, you guys were 20-6 in May, because the no-hitter was the last game in April, I believe. And you guys went 13-1 at home right after that. So momentum definitely switched,

Larry: And we had a lot of good, young talent in ’69. Perhaps not enough to win a championship, but by September we at least had a chance.

Jim: Right. And in 1969 you were in your sixth season, and you were a veteran instead of that young 17-year-old kid who came up in 1964.

Larry: Well, that’s for sure. You had to learn pretty quickly if you were a starting pitcher back then, because they expected a little bit more than they expect now, in terms of the number of innings you pitch. And so even though I was still pretty young, I had a lot of innings behind me, and I’d gotten to the point where I felt like strategically, I knew how to work my way through a lineup.

Jim: Right. And despite the team’s poor start, speaking of innings pitched, you had career highs and wins with 20; innings pitched with 305. The only time you broke 300 innings, 20 complete games, and your lowest full season ERA at 2.33. How did it all come together for you that season, that made that one such a special one for you, personally?

Larry: It started, I think, in 1967 in San Pedro de Macoris, in the Dominican Republic. I went down there, basically to try to learn to do the things that I’d seen veteran pitchers do. And that was to change speeds and throw breaking balls behind in the count, and to pitch around hitters with a base open, where I perhaps had a better shot at the next batter. To do the little things that guys who had been around for a while were capable of doing. And I had a great year down there, and was able to do those things, and we won a championship. Actually the only championship team I was ever on as a professional.

When I back in 1968, I was better, but still not quite good-enough at doing those things. In 1969 we got a catcher, Johnny Edwards, in a trade, and we continued to work on those things during spring training. And I really got into a good groove, and I stayed in that groove mostly all year long. And I think it was a combination of experience, and having a catcher that I depended on and who seemed to be able to pick up on the vibration of what I was thinking about doing, what I wanted to throw. It got to the point where I think we both felt like, game after game, inning after inning, it would be hard for the other teams to score.

Jim: Edwards was really important to your career and to your confidence when you went to the mound, wasn’t he?

Larry: Yeah, he really was. And while he was more a veteran player than I was, he wasn’t as stubborn as some catchers I’d thrown to before he got there. A lot of catchers, especially if they’re catching a young guy that doesn’t have a lot of experience, feel like they know what the pitcher should throw better than he does. And Johnny wasn’t like that.

He basically allowed me to call my own game. The way he worked, when he felt like that maybe I wasn’t making the best choices, was to talk to me between innings. And say … I remember one game in San Diego, “How come you’re not throwing your fastball?” “Well, I don’t think that I have a very good fastball.” “Well, how many have they hit? How many did they hit hard?” “Well not any, yet.” “Well start throwing it more. It’s good, whether you know it or not.”

That was his way, you know? It wasn’t like just putting the fastball sign down, time after time, and then to come out to the mound and tell me what to do. And you know, just that slight difference in the way we communicated, I think made me feel more important, smarter, better, whatever. It gave me confidence.

Jim: Yeah. And you’ve also mentioned the confidence you had when he would put the breaking-ball sign down with two strikes. That you had every confidence that you could throw it in the dirt and he would block it.

Larry: Right. Exactly. Not only with two strikes, but with two strikes and a man on third. Which, really puts the… You know, I mean he puts the pressure right on himself, because he would call for a slider, and then he would tap the dirt behind home plate. Meaning he wanted me to throw it in the dirt, and get the hitter to chase it, trying to strike him out. Which obviously with a guy on first, especially with less than two outs, a strikeout is really important.

Back then, most pitchers didn’t really pitch for strikeouts. Yeah, there was Sandy Koufax, and Nolan Ryan was starting to come into his own as a strikeout pitcher, but for most pitchers any kind of out would do. Get a guy out with a sinker on the first pitch, it was better than having to throw five pitches to strike him out. It wasn’t quite as big an issue with this as these days. But when there was a man on third and less than two outs, it was a sure way of preventing a runner from scoring.

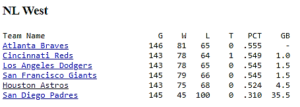

Jim: Right. So your relationship builds; things work pretty well. You’ve got 19 wins by September 13th. The Astros are only three-and-a-half games back of the Braves. You’re playing the Braves in Atlanta, so there was plenty on the line for you and the team in this particular game.

Larry: There was everything on the line. And I think that’s why it’s the game I’m most proud of. I never got a chance to pitch in postseason. That would’ve been even more pressure. But as far as the way my career went, on the teams I played for, it was the most pressure-packed game of all. Because if we could beat the Braves, we’d only be two-and-a-half back. There were, I think, probably three weeks left to play. So we really had a shot to win the division that year. And as you mentioned, I had 19 wins already. So I was pitching personally for my 20th win. And as a teammate, and a leader of the pitching staff, I was pitching to keep us in the race and move us forward. So it was, you know… I felt going into that game, like I had to win it. So it was important. I guess they say, you know, every game is important. And back then, there was no free agents. So every year was a one-year contract, which made every game even more important.

But this particular game was critical. Then probably I really didn’t pitch in that many games that were that important during my career.

Jim: And you’re facing a tough lineup with Alou, Cepeda, Rico Carty, Hank Aaron, and others. Were you keying in on anyone in particular, or are you just trying to navigate a pretty tough lineup there?

Larry: Yeah, I wasn’t going to go out there and try to pitch a no-hitter. I was going to try to go out there and pitch as well as I had been pitching down the stretch. And yes, it was a tough lineup. Fortunately most of those guys you were, well, all those guys you mentioned were right-handed hitters and that was helpful because I was a right-handed pitcher. But you know, some of them were in the Hall of Fame, and some that weren’t like Rico Carty, might’ve been even better as far as being an offensive player.

Jim: Right.

Larry: So yeah, that was … You know, to me it wasn’t [my goal to] pitch a shutout or pitch a no-hitter. It was just try to keep them… keep the game close and give us a chance to win it. So I mean, I would’ve been happy to pitch a one- or two-run game if we’d won it. But as it turned out they hit the balls to the fielders, and I did better.

Jim: And you guys were facing Phil Niekro, I mean a 20-game winner himself, and a knuckleball pitcher to boot. He was known to mess up a line lineup for days after he pitched, just trying to deal with that knuckleball.

Larry: Yes, and that was an issue in this particular game, as it was in a game I pitched earlier in my career in New York, where I had a no-hitter going into the ninth, but we didn’t have any runs.

So if you’re on the road, you pitch the bottom of the ninth and finish the no-hitter, or the game’s not over, because it’s still nothing to nothing. So you have to go back out in the tenth to try to pitch the no-hitter. And I came to New York, I gave up the hit in the ninth. In this game in Atlanta. I got the first two guys out. It wasn’t a perfect game. I walked a couple of guys, but Felix Millan chopped a ground ball in the hole at short. And our shortstop, Denis Menke, wasn’t one of those power-arm guys. So he tried to grab it, throw quickly, and the throw was in the dirt. I think Millan probably would have been safe anyway.

But the first-baseman dropped it, scored a hit. I felt like it was a legitimate hit. I also felt like there were shortstops in the league that probably could have planted and thrown, and thrown him out. So it was that close to pitching a no-hitter for my 20th win to get closer to the Braves in the race. But just like the game in New York, we didn’t have any runs off Phil Niekro. So just completing nine no-hit innings wasn’t going to get us the win. It wasn’t going to get me my 20th win. We had to go on in to extra innings.

Jim: Yeah I did want to want to ask you if you got a sense as that game was going along, did you think that one run would take that game?

Larry: I don’t think so. It’s hard to really remember what your thoughts are in a game. I know my thoughts were, going into the game, that it was a critical game. Generally speaking, my thoughts were in any game that you can’t expect to pitch a shutout, but you just try to keep your team in the game. But to think at some juncture within the game I did think one run would win it, I kind of doubt it, you know, maybe in the eighth or ninth inning. But … It’s hard to remember.

Jim: Well, I wanted to ask also, you just touched on this, what it’s like to go out in the bottom of the ninth on the road knowing: look, I might get these next three guys out, but I’ve really got to get six more guys out to get the no-hitter and win this game.

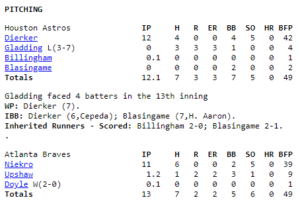

Larry: Yes, that’s true. And it wasn’t the first time. I had a game like that in the Astrodome against Steve Carlton. In that game, it wasn’t nothing to nothing, it was one to one. But you know, after getting them out in the ninth, you’ve got to go back out on the 10th. And that one I ended up going 11. In this one in Atlanta I ended up going 12. I don’t think you’d see that anymore, because I gave up a hit in the ninth. So the manager wasn’t going to leave me in the game to give me a shot at the no-hitter. It was gone. He left me in the game because he thought I had the best chance of putting a zero on the board in the tenth, which I did.

Jim: Right.

Larry: But that just doesn’t happen anymore.

Jim: Right. Because I mean, Niekro was pinch-hit for the 11th inning. John Mayberry pinch- hits for you in the 13th. I mean, you had given up a couple of other hits by then, but still you weren’t hit for until the 13th inning. You guys score a couple of runs, go up two-nothing but your closer, Fred Gladding, couldn’t hang onto it. And Bob Aspromonte ends up winning the game on a bases-loaded walk. So it’s 3-2 loss, when not so long earlier things might’ve been different.

Larry: I think if there was ever a game in my career that I could call a turning point, that was it. Because with a 2-0 lead and Fred Gladding on the mound, I believe that everyone on the field and on the bench believed that we were going to win that game and close within two-and-a-half and then losing it. It was just like a kick in the gut.

If there was ever a game in my career that I could call a turning point, that was it … it was just like a kick in the gut.

Now we’re four-and-a-half out after expending that much effort to finally get the runs, to finally win the game. The Braves from that point on only lose a few games the whole rest of the year. And the Astros from that point on only won a few games the whole rest of the year. It was just as if that one inning [decided] the pennant race.

Jim: Yes, because I checked the records and the Astros went 6 and 14 after that game, and the Braves went 13 and 4 and won the division by three games. So sometimes that stuff can be overstated, but it doesn’t look like it was overstated in this case.

Larry: No, at least with regard to those two teams. And I should mention that even had  we beaten the Braves in that game and closed to within two-and-a-half, there were four other teams, three other teams in the race. There were six teams in the division. And the only team that was more than three-and-a-half games out was the Padres. So it was up for grabs for anyone to win it. But the Braves eventually did. And so winning that game, you know, put them back one more and us up one more. Whether that changes about or not, nobody will ever know.

we beaten the Braves in that game and closed to within two-and-a-half, there were four other teams, three other teams in the race. There were six teams in the division. And the only team that was more than three-and-a-half games out was the Padres. So it was up for grabs for anyone to win it. But the Braves eventually did. And so winning that game, you know, put them back one more and us up one more. Whether that changes about or not, nobody will ever know.

Jim: Well, it also didn’t help … I checked today: you guys were 3 and 15 against the Braves that season. And you know that’s more than enough, if you guys had just broken even against the Braves. You would have won the division alone, right there, just in head- to-head games.

Larry: Oddly enough in that same year, 1969, the Mets beat the Braves in the playoffs. The Mets had a winning record against every team in the National League that year, except for the Astros. We beat them 10 out of 12 times. So I guess that goes under that thing that we throw everything under the same umbrella. That’s baseball.

Jim: Yeah. Because when you look at the season records of those teams and who they did well against and who they didn’t, it doesn’t always even out. And if X team and Y had played in the playoffs, yes, history might have certainly have been different just based on how those teams compared to each other all year long.

Larry: Well, that’s… that’s why things happen. It’s more the rule than the exception.

Jim: Yes. And it should be noted also, just in fairness, you did get your 20th win in your next start, September 17th against the Giants. [You beat] a guy named Gaylord Perry two to one, and Jim Bouton pitched a two-inning save for you in that one.

Larry: That was a … an interesting year. I didn’t throw any where near as well in that game against the Giants, as I had against the Braves. But I still was motivated because it was … I had 19 wins and actually they asked me if I wanted an extra day, because I pitched 12 innings. I said no. Maybe I needed an extra day in terms of how hard I was throwing, or something like that. But obviously seven innings and one run isn’t all that bad. And I got my 20th win. And Bouton, who wrote Ball Four after that season, was actually an excellent pitcher for us that year.

We picked him up about halfway through from the Seattle Pilots, the team that became the Milwaukee Brewers. The Pilots were only up in Seattle for a year or two. But Jim was not doing that well there. He got over there, over with us … I guess he felt the excitement of a pennant race, which he’d been in before as a young pitcher with the Yankees.

Jim: Right.

Larry: And so he pitched really well for us, and he got that save. He ended up striking out more hitters that season for us than he pitched innings. And we had, I think we had three pitchers on that team — Don Wilson, Tom Griffin, maybe Jim Ray, and Bouton — we had three or four pitchers who had more strikeouts than innings, which was really unusual back then.

Jim: Right. But you did finish the season with the 20 wins. The Astros had their first at least .500 season. Still in all, I guess there was a feeling of what might’ve been?

Larry: Yeah, it was a disappointing season, because after starting 4 and 20 and getting over .500, you’re close to first place — was really stimulating. And then the letdown ending was kind of like the slow start. I guess we just weren’t quite good enough, not quite mature enough. It was basically a pretty young team.

And we just didn’t have enough. But it was exciting nonetheless because it was the first time that any of us had experienced the pennant race. Little did we know that we would never experience it again. The [Astros had to] wait till 1980 before they won the division. 1979 they were in the race, but it was a long time coming.

Part of it was some of the young players that were in that pennant race for us ended up getting traded. Probably the most important was Joe Morgan, who went to the Reds and became an MVP of the league a couple of times. I think back then that team we had in 1969, had we just kept it together and not made any trades, that we probably would have been in some other pennant races, and maybe won one.

Jim: It ended up not working out, even after the Morgan trade. When you guys got Lee May and Helms and those guys, I remember Bob Howsam saying, “Gee, I think I just gave Houston the pennant this year.” That was 1972. But it really didn’t work out that way, because the Reds passed the Astros and went on to win in 1972 and didn’t look back after that.

Larry: Yeah, and they got Jack Billingham, too, in that deal. And Jack was a good pitcher for us and he probably was underappreciated as an Astros pitcher. But as a pitcher for the Reds with that little extra offense, he became one of the best in the league.

Jim: Right.

Larry: So you know, Morgan was the most obvious because he became an MVP. But Billingham was really a big part of that Red Machine too.

Jim: He won 19 games for them twice.

Larry: Yes, he could keep the ball on the ground. He had a good sinker and slider. He could pitch around the knees very effectively. He did something when he was with us, I think that year before he got traded. It is really probably as difficult as anything a pitcher can do. And that’s to win a game 1-0 and get the run in the first inning on the road. So you get the run in the top of the first and get no more. So you got to put nine zeros up there to win the game. Well he did that in San Francisco, and he came right back in his next start and did the exact same thing in Cincinnati. That might’ve been why the Reds wanted him.

Jim: Sure. If you can’t beat them, join them. So he certainly was a major contributor and very, very successful. It was a good match for them. And you know, he had been a good pitcher for LA and for you guys before that, but he really found the right situation there.

Larry: Any pitcher that went from an ordinary team to the Big Red Machine, any starting pitcher would have had a better record. Because they scored more runs. So you’d end up winning some games you might have lost because of their offense. And maybe getting some no-decisions in games where you would have had a loss. Starting pitchers depend on the quality of their fielders and hitters a lot. And so the records reflect that.

Jim: Well, you certainly had the record in 1969, and I appreciate you taking some time to talk with us about that year and about this game in particular. That was quite a moment in time, wasn’t it?

Larry: Well, Jim, I never get tired of talking about that game — for all the reasons that we’ve just discussed. But it also reminds me of something Don Larsen said when a reporter asked him if he ever got tired of talking about his perfect game in the World Series. And Larson said, “No, why would I?”

Jim: Sure.

Larry: It’s fun to talk about your best game.

Jim: And that is — you think that was your best game, considering everything that was —

Larry: Yeah. I think so. Definitely, you know, not as many strikeouts as I had in other games. But considering the quality of the lineup and the importance of the game in the pennant race, I would say yeah, definitely. That was the best game I pitched. I certainly had better stuff and better control than I had in the no-hitter I pitched against the Expos in the Dome. So that was it.

Jim: Well, it’s nice that you still have that moment, and that you’re proud of that. Appreciate your time today, Larry.

Larry: Okay, thanks, Jim.