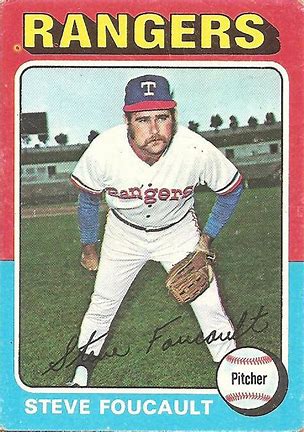

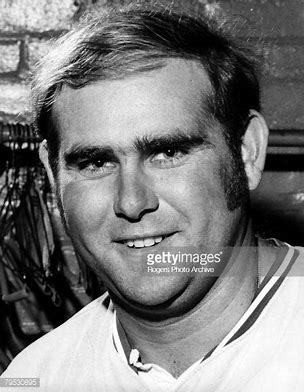

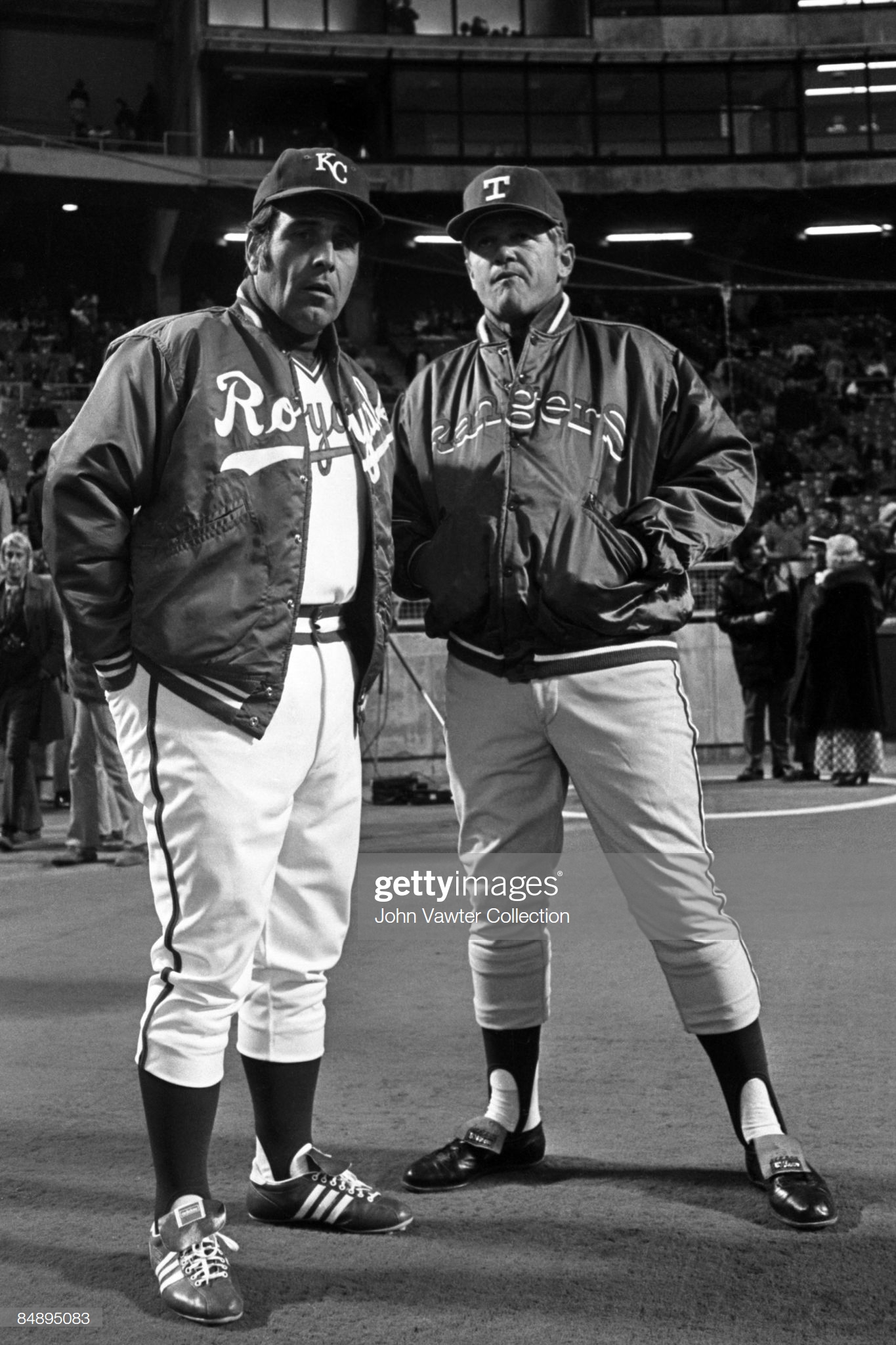

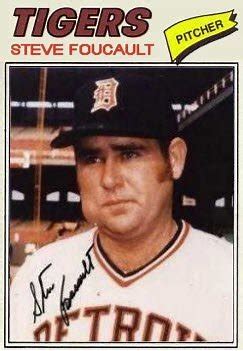

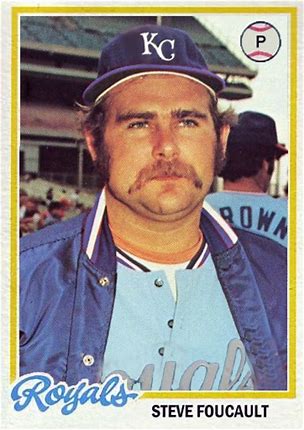

Steve “Fookie” Foucault was a first-rate closer for the Texas Rangers, Detroit Tigers, and  Kansas City Royals during the 1970s. He was part of the 1974 Rangers club that gave the eventual world-champion Oakland A’s all they could handle for much of that season, and possibly saved the franchise for the Metroplex.

Kansas City Royals during the 1970s. He was part of the 1974 Rangers club that gave the eventual world-champion Oakland A’s all they could handle for much of that season, and possibly saved the franchise for the Metroplex.

But Fookie’s journey to the big leagues was far different from what he envisioned when he signed – as a position player — with the Washington Senators in June 1969 as a 43rd-round draft pick.

Jim Haught: You were born in Duluth, Minnesota, October 3, 1949. But you didn’t live in Duluth very long?

Fookie: Thanks goodness, no. My father moved the family to Miami, Florida when I was five years old.

was five years old.

JH: And were you always the athlete type?

F: I was. My father was my coach for years. I was the shortstop, the pitcher, catcher, third-baseman. And we had about five or six guys who could do the same thing.

JH: Were you primarily a baseball player all the way?

F: I was. I never played any other sports besides baseball, fortunately.

JH: Really? I mean usually, somebody who’s the shortstop is also the pitcher, is also the point guard in basketball, and played football or whatever.

F: I was a little guy; I never grew up like all the other kids. When I finished high school, I was 5’6” and weighed 140.

JH: Did you have a primary position? Were you the guy who was the best athlete, and so you played short, or – did you have a good arm?

F: Well, I was probably – I had a great arm – I was probably the top two or three best players on my team until I was about 12 or 13, then everybody else was twice my size [laughs]. I was still a good player, but I wasn’t one of the top two or three anymore.

JH: So what happened when you hit high school and beyond, if you were still a little guy?

F: I was still a little guy in high school. I didn’t make my high-school team until I was in the 12th grade. Played on the junior varsity through 11th grade. Made the high-school team as a senior, and played right field. Then I became the third-baseman. The [original] third-baseman was a junior, and he was team captain. But he had a bad start to the year, so after about four games, the coach moved me to third base and benched the third-baseman — the team captain!

JH: Wow! That’s pretty strong.

So after high school, did you get offers from junior colleges, or that kind of thing? You went to junior college first, right?

F: I did. I went to junior college at South Georgia College, which is now South Georgia State College, and a couple of my high-school friends who were a year older than me went up there to school, and the coach loved them, because they were two of the better players on the team.

[One of those players was longtime Twins/White Sox third-baseman Eric Soderholm.]

All of the coaches in Miami wanted me to go to Miami-Dade North or Miami-Dade South, but I thought that would be like going to high school; I wanted to go away to college, like you’re supposed to. So that’s how I got up there.

I went up and visited that school and loved it up there; there were probably 10,000 people in the whole town. It was great.

JH: Were they interested in you, or were you interested in them? How did that work?

F: Well, the coach called my high-school coach again: “hey, you got any more of those guys, like Soderholm?” My coach said, “Hey, I got a pretty good player you might probably like.” So I went up there, and that’s how I went to South Georgia.

Junior college, and getting signed

JH: So how did junior college go? What position did you play?

F: I was a third-baseman. Actually, I got to play both years I was there.

The first year, we won the state championship and beat the team from Alabama, and the team from Florida beat us – Manatee Jr. College. The next year was the same thing: we won the state championship and we beat Alabama, then we beat the Florida team my sophomore year, and went to the Junior College World Series in Grand Junction, Colorado.

I signed out of junior college, with the Washington Senators.

JH: How or where were you being scouted in those days? It was so much different then.

F: After my freshman year, I went back to Miami and played Legion ball, because I was still at an age where I could play. I was playing third base, and our catcher got hurt, so I did some catching, too. And I was a good catcher.

A couple of scouts did call and wanted to see me throw, for infield practice. They were Scouting Bureau scouts; they weren’t affiliated with any particular team. One of those guys got me drafted by the Senators. He recommended me, and I guess the Senators scouts came and watched me play.

JH: They didn’t have any other thoughts for you – beyond third base – at that point?

F: No. Because I never pitched in high school or college.

JH: But you had the good arm. What kind of hitter were you?

F: I was a good hitter; wasn’t a power hitter. Line-drive hitter. And I think I hit over .300 in college both years. It’s been so long, I don’t remember [laughs]. But I remember I made the Junior College World Series All-Tournament Team as a third-baseman.

I’m sure that had something to do with [getting signed] because I had a really good tournament. We won the first two games, then lost the next two. And the first game we lost was to the eventual winner, Panola Junior College.

JH: So in junior-college ball where you came from, was that pretty highly regarded as “feeders” for the other schools? Some of the schools in California, if they think you’re not quite ready for Stanford or USC, they’ll send you to a junior college for a year or two.

F: Well, I never had any offers to go to a four-year college, until after my junior college. I got letters, and a bunch of people wanted me to come to their four-year school with scholarships.

JH: But you decided that getting drafted was a better way to go.

F: Yeah, I just figured, “it’s now or never.”

So I signed for $200! [laughs]

JH: Wow! And where was your first stop?

F: Wytheville, Virginia. That was a short-season team. Actually, I was holding out for $200; I didn’t sign until the middle of July!

JH: For $200?

F: Well, they gave me $200. I said, “well, I need more than that. That won’t even pay for gas in the car (that I didn’t have yet).” So I ended up getting $2,000. But I had to be on an active roster with a minor-league team for 90 days.

[He only got seven at-bats with the 1969 Wytheville Senators, and went 2-for7 (.286).]

That meant that the next spring training, I had to go back and make a team and stay there for another 45 days to get my $2,000!

JH: Wasn’t that how a lot of bonuses were done back then? They would be prorated for each jump – that you had to stay on X roster for a given period of time?

F: Yeah. Some guys, like if you made AA, you got another $1,500, or – that’s why they didn’t do a lot of promoting in those days!

JH: And I’ve seen guys get sent down at 89 days, to avoid paying a [90-day] bonus.

F: Right! They did that.

JH: So, your first exposure to pro ball, how do you feel like that went?

F: I was there for six weeks, and I was like the fourth third-baseman on the team. Our first-string third-baseman was [future major-league player, coach, and manager] Pete Mackanin, who was my roommate. He was a fourth-round draft pick, so I wasn’t gonna play.

A Catcher is Born – Or Not

JH: A classic case of who they have something invested in, and who they don’t?

F: Pretty much. And I could see the writing on the wall that I wasn’t gonna play third base. So I told the manager, “you know, I can catch, too.” So they stuck me in the bullpen. I was the bullpen catcher and fourth-string third-baseman.

And I was a pinch-hitter. On the last day of the season was a doubleheader. And the manager decides to stick me in the second game — at third base.

Now, I hadn’t played third base in five weeks. I don’t even remember where I batted in the order, but I went two-for-four, drove in two runs, and made three diving plays at third base. The only game I got to play.

JH: You must have showed enough that at least they brought you back.

F: Yes. Next spring, they put me at third base again, and I made the team in Class A [the Anderson (GA) Senators]. But I hurt my knee in spring training. So they could have released me right then, and I wouldn’t have known any difference.

But they kept me around, because I had a really good spring training; I was hitting around .500. And we only had a week left before I got hurt. So they brought me to Anderson and kept me around, and I came back after my knee healed up – whatever that meant back then. It was still damaged, but good enough that I could run. And it still is [damaged], to this day.

I got to play, but it wasn’t the same; I couldn’t hit the way I did before. My stance was different. [Actually, he hit .341 (14/41), but with only one extra-base hit.]

So I’m thinking, “this could be the end of the line, here.” So the manager called me into the office. I thought, well, this is probably it.

But it wasn’t!

Into the Fire: Relief Pitching

He said, “you know what? The farm director says you have a great arm. You want to try pitching?”

I said, “yeah, OK.” It was either that or go home, so I said, “I pitched a little when I was a kid. I know a little bit about it.”

And the manager said, “Well, I’ll get you into a game one night when we’re getting our butts waxed,” like they always do.

So they brought me into the game that night! It was 3-2. We were playing the Greenwood Braves. It was about 105 degrees.

He brings me in, and I pitch the bottom of the seventh inning. I pitched two innings, no runs, and struck out five guys. We still lost 3-2.

JH: All fastballs?

F: That was it! Didn’t know how to throw a breaking ball.

The next day, I pitched again! Three innings, against Buddy Bell’s team – the Sumter Indians. Struck out six or seven guys, and got the win in the tenth inning.

I just pitched from then on.

JH: No thought of going back to third, or anything else? Did they even use you as a pinch-hitter?

F: No, but back then, pitchers hit for themselves, so I did get to bat a little bit. That was fun!

JH: When you hit the end of a season like that, and you’ve changed positions, do you get any kind of feedback from the organization about what they’re thinking about you, or if they have any plans for you? Or is it still, “we don’t have that much invested in you. We’ll see you in the spring, and see what happens”?

F: You really never know if you’re going back again until it’s time that they have to tender you a contract at a certain point in time, and they give you, like, a $50 raise per month. So I went from $500 a month to $550!

In 1971 they sent me to Burlington, North Carolina, which was a high-A team. I wasn’t getting to pitch a lot, because they had a lot of older pitchers on that team. So I’m thinking, “here we go again.” They called me ino the office and they sent me back down to the low-A team again, and I got to pitch a lot, which was good. I needed to pitch. I didn’t have much experience pitching. And I had a pretty good year [42G, 5-4, 4.50 ERA, all in relief].

1972: Two All-Star games in one season, and a jump from A-ball to AAA

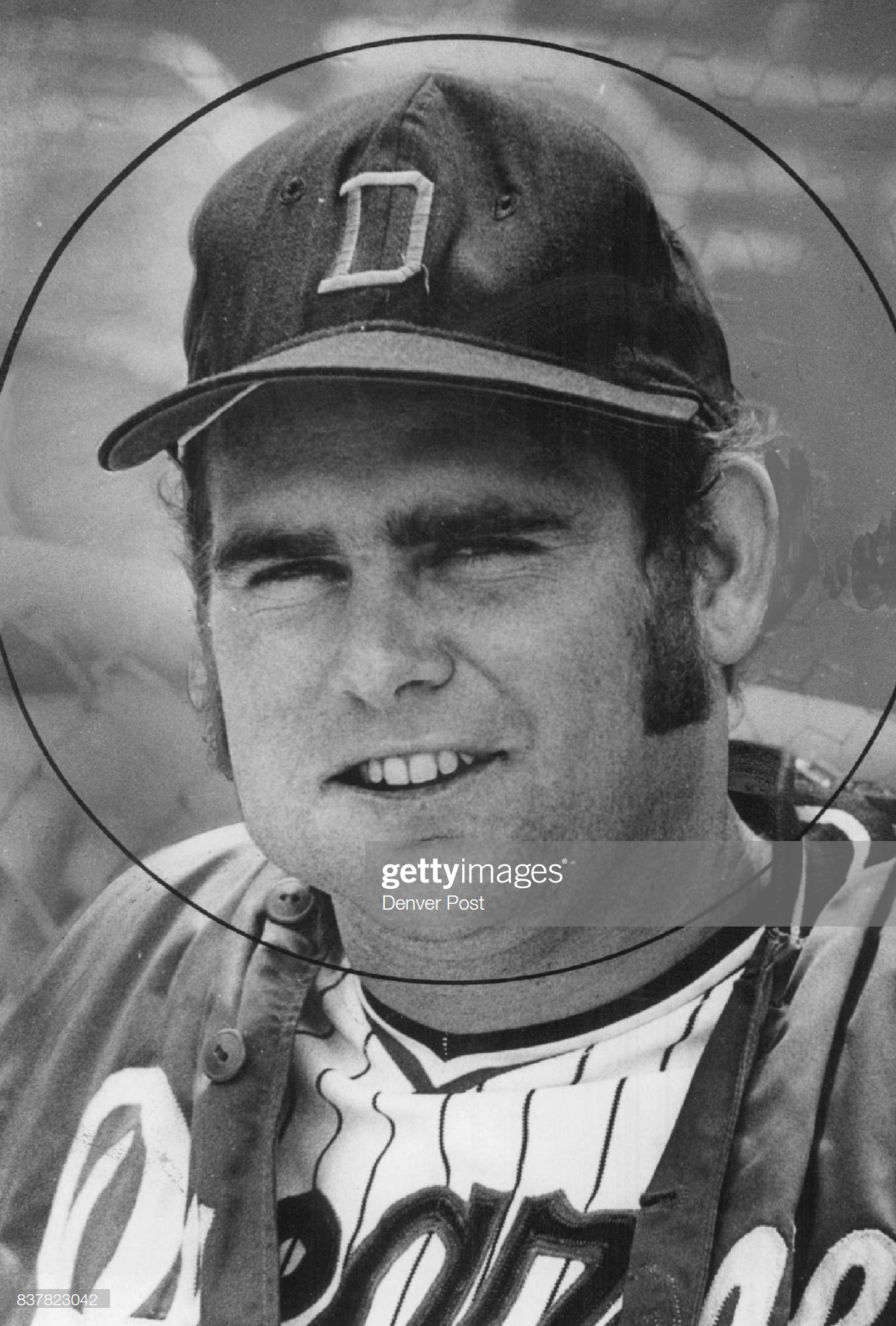

F: So the next year, in 1972, they sent me back to Burlington again! Pitched there half the year, then went to AAA for the last six weeks of the season. It was after the All-Star game that I pitched in in A-ball.

JH: You went from high-A to AAA?

F: Yes. In Denver.

JH: And you actually pitched in All-Star games at both levels that season?

F: I pitched in the All-Star game in Burlington, and if I remember right, I pitched two innings – the eighth and the ninth. The game was tied at 2, and I didn’t give up any hits or runs. I think the game went 11 or 12 innings.

They sent me to Denver right after the game, so I had to go to my $100/month trailer, pack my stuff up, and get a U-Haul. So I drove to Denver.

I was there about ten days, and I got to pitch a lot. In something like 5 of the 10 games I was there, I pitched against the Cubs AA team that [future Chicago Cubs manager] Jim Marshall managed. I pitched really well, and Marshall was gonna manage one of the AAA All-Star teams. One of his pitchers got called up to the big leagues, and he told our manager that he wanted me on his team! So it was cool.

From thrower to pitcher

JH: At what point did you become more of a pitcher than just a fastball guy — developing a slider, and the rest of it?

F: Probably that year, because I had a manager [Bill Haywood] down in Anderson in 1971 who was a pitcher, and who was a college coach as well. He was an ex-sergeant in the Marines. A tough guy. He was 6’4” and probably 230. Solid as a rock. He was tough on his players, but for the right reasons. And he taught me a lot.

JH: What kinds of things?

F: I think he must have been a sidearm pitcher, too. He taught me a lot about pitching sidearm, and how to hold different pitches, and what to do. Back then, you didn’t talk much about setting the hitter up or that sort of thing; you just tried t o get him out! Whatever was working good, that’s what you threw.

o get him out! Whatever was working good, that’s what you threw.

JH: Was your natural motion three-quarter?

F: It was, and then I started throwing three-quarters to left-handed hitters, and sidearm to right-handed hitters. Every once in a while, I’d mix it up, but that’s pretty much the way it went.

JH: So you weren’t talking about arm slots, and that kind of thing?

F: No, and spin rates, and all that. We didn’t have any of that going on [laughs].

JH: So if you’re throwing sidearm to a right-handed hitter, is that ball gonna run in on him?

F: Yeah, it’s gonna run in hard, and it’s gonna sink.

JH: So you pitch in the AAA All-Star Game – was that Denver?

F: Yes, it was Denver. That was 1972. First year of the Texas Rangers. I think it was 1972 that we had a co-op team in Burlington: half Phillies players and half Rangers players. A bunch of guys ended up playing in the big leagues with the Phillies [Jesus Hernaiz, Dane Iorg, Erskine Thomason].

JH: How did the co-op thing work? I’ve talked to some guys who said it was a disaster when they did that, because you got mixed messages, and the organizations might want different things.

F: It was definitely different, but it was kinda cool, because you got to meet players from other organizations. And it gave you a reason to follow that other team, because you knew some of those guys.

JH: I’ve had it described to me that a co-op team is a situation where an organization has too many players, and they’ll put players from two or three organizations together, to get them more playing time, and more people get to see them.

F: Yeah, there wasn’t a lot of prospects on our team, but a few of the guys got to the big leagues.

[Ten players from the 1972 Burlington team made it to the big leagues – an exceptional total.]

1973: Going to the Big Leagues

JH: So you finished the season in AAA [48G, 10-2, 1.65 ERA, 19 SV, 94K in 82 IP]. Now we’re talking 1973. How did spring training go for you?

F: It was good.

JH: Are you getting noticed in the organization now – from a suspect to a prospect?

F: I’m not really sure [laughs] because I was never described as a prospect. Back then, prospects got invited to Instructional League, and they got extra teaching and got to play games, and stuff like that. It started around the end of September, and it was probably 30-40 games. It was people like Jeff Burroughs; I was never invited to that.

JH: No “fall ball” for you; were you playing winter ball yet?

F: Oh, no. Back then, you didn’t play winter ball unless you were a veteran AAA player or a major-league player. They didn’t invite AA or [young] AAA players to play in Venezuela; it was all major-league players.

JH: So you were pretty much done in September?

F: Yeah! I had to go back to Florida and get a job – a real job!

JH: What did you do in the offseasons?

F: Couple of years, I worked with my dad, doing ironwork. And I made more doing that than I did pitching in the big leagues!

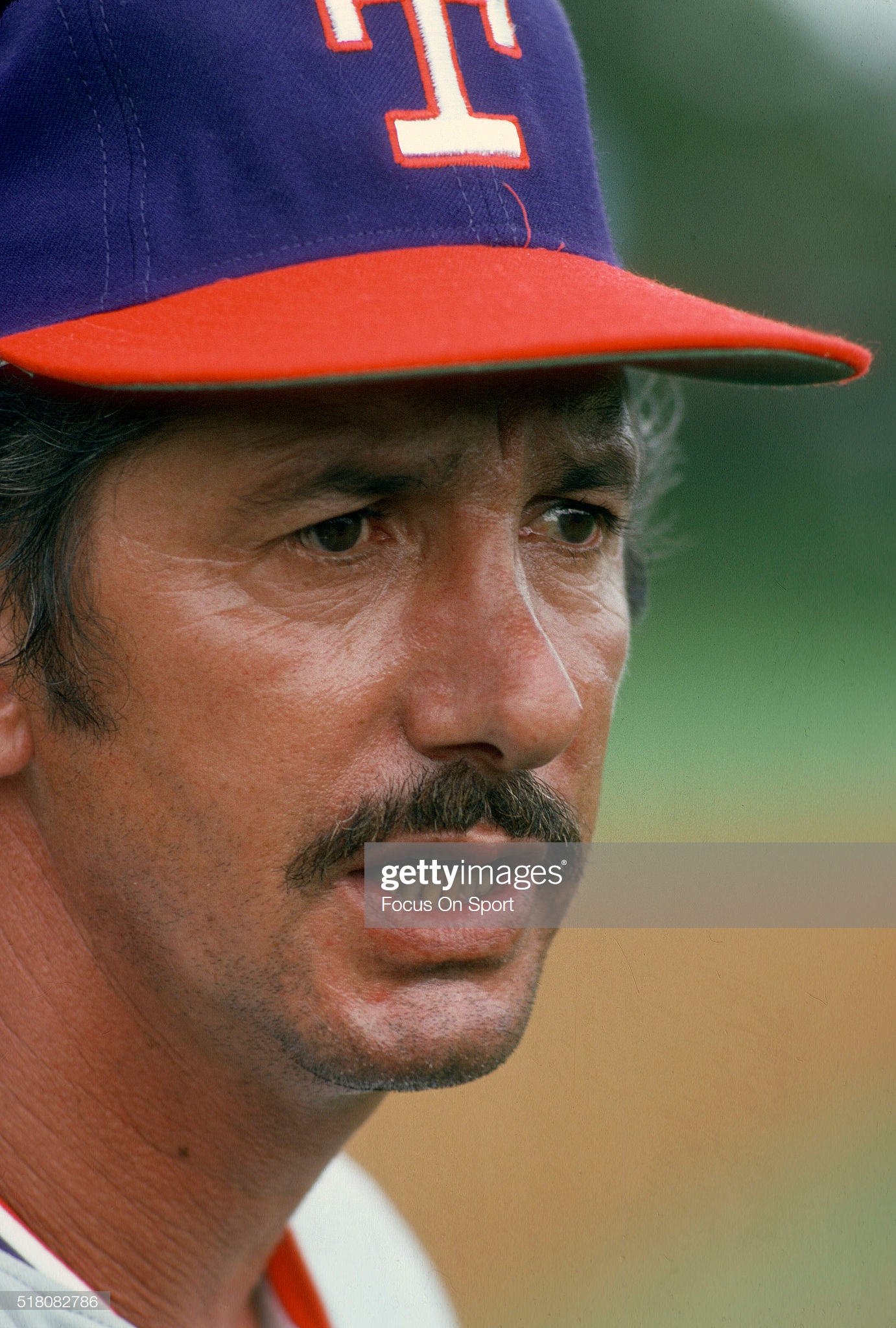

Whitey’s closer

JH: So in 1973 spring training, what kind of feel do you have for how it’s

going to be, and where you’re going to pitch?

F: Well, I was invited to spring training, and the new regime with Whitey Herzog was under the impression that they were there to develop and have a young team and develop people who would be around for a while together.

JH: When did you know you were going north with the big club?

F: That didn’t happen until probably about a week before spring training was over. Whitey told me that I would be on the team. So he called me into the trailer in Pompano Beach – that was his office.

JH: So they tell you that you made the team, and you go north to Texas. Were you the tenth man on a ten-man staff, or how was that?

F: I don’t think — at that point, Whitey had his starting pitchers. And I was not a starter; never was, and never did start a game anywhere. Back then, you were either a starter or a reliever. And that year, at least, it depended on how you pitched as to where you would come into the games, after about a month or so.

JH: Was that still with a four-man starting staff?

F: No, it was five. There might have been four for the first couple of weeks, because there were a lot of off-days built-in for weather.

JH: Four starters and a swing man? On a ten-man staff?

F: I remember some teams would even go with nine pitchers for the first two or three weeks.

JH: And I would assume that hardly anyone was on a pitch count?

F: No, we didn’t know what a pitch-count was! As long as you felt good, or felt like you could pitch, you were gonna pitch – no matter if you were sore or not.

Being sore wasn’t a big deal back then; you pitched anyhow, because you were afraid someone else was gonna get your job.

JH: And I guess athletic trainers weren’t as developed as they are now, about how to take care of you.

F: And there was only one of them! One trainer for 25 major-league players. But the training room wasn’t a place you wanted to be. You didn’t want to be seen in there, unless you were on the scale getting weighed, or something like that.

JH: So 1973 starts, and you get some appearances. Did you feel like you were working your way up? How did that develop for you?

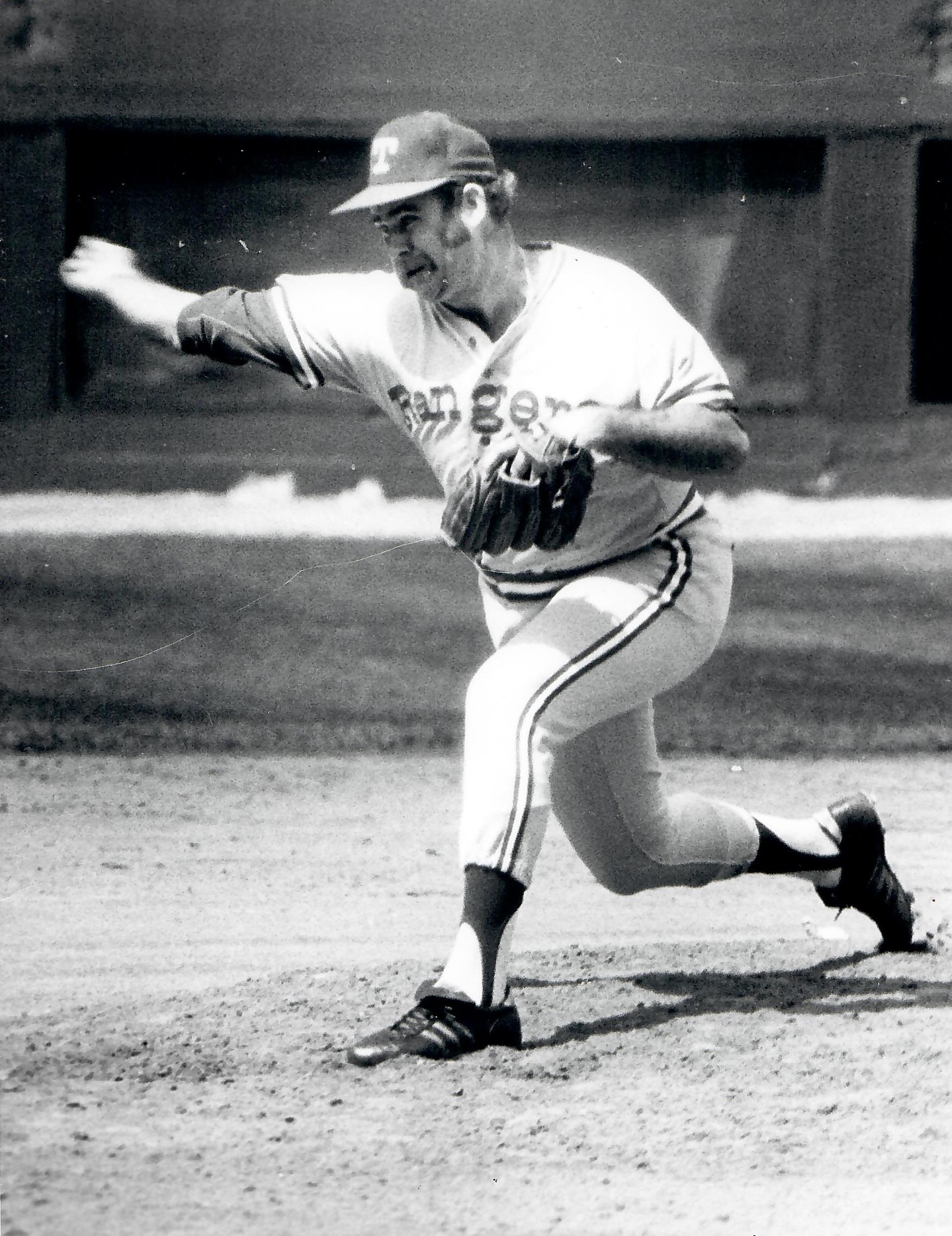

F: Actually, Whitey started me out as being the closer. I pitched in the first game of the year, and he started me out coming in at the end of the game, whether it was close or we were losing or winning. Back then, the closer pitched in games when you were losing by a run in the eighth or ninth inning. You didn’t bring the eighth or ninth pitcher in, because they might give up runs, and now you’re losing by five or six runs, instead of one.

JH: So you started as the closer; as the season went along, how did that work for you? Did you stay that way, or did they go with the hot hand, or — ?

F: No, I pretty much stayed the closer the whole year. There weren’t that many games to “save” [laughs] because we were not very good [57-105]. We were all 22, 23, 24 years old. There were a few older guys left over from the 1972 team, but we lost with younger players in 1973.

JH: That was supposed to be the philosophy: to develop younger players.

F: And Whitey Herzog was known as being a great developer of young players. That’s why they brought him to Texas, with the hopes of teaching these young guys how to play, and do the game right – as it’s supposed to be played. That was the assumption he went under the whole year, until you-know-what hit the fan!

Whitey got fired [9/7/73], and Billy Martin showed up, like, the next day!

Actually, Del Wilber was there for one day, so we had three managers in three days. And a buddy of mine was in town visiting, and he saw all three of them!

A new sheriff rides into town: Billy Martin

JH: All of a sudden, Billy Martin gets fired by the Tigers, and so he becomes available, so Whitey gets fired –

F: And you know what? It’s probably the best thing that ever happened to Whitey! Because he went on to much bigger and better things [in Kansas City and St. Louis].

JH: There was a new sheriff in town!

F: Yup! He wanted to make sure we knew who was the boss. And we all figured that out, real quick!

JH: You said that Martin made it clear when he came in that there was a new sheriff in town. But he’s a guy who liked veterans!

F: Absolutely! He hated young players!

JH: Did he make that clear – that he was gonna basically kind of shitcan that [player-development] philosophy and win right now?

1974: A roster makeover, and a competitive team

F: Well, you kind of got that idea. Not necessarily at the end of 1973, but the next spring, you kind of noticed that, because we still had some young players, but they brought in a lot of older, veteran players like Jim Fregosi, Cesar Tovar, Leo Cardenas. All of them probably had 10+ years in the big leagues.

Those were the kinds of guys Billy liked, because they didn’t make mental errors. They still made physical errors, because everybody is gonna do that. But he didn’t like young players, because of the mental errors that they made.

JH: So did he “take” to you – you’ve said that he didn’t really care for pitchers, so what was your relationship like at the beginning? How did you feel you stood with him?

F: Well, Billy was like a Jekyll-and-Hyde guy. As long as you were playing well, he loved you. But when you started – when you had a little problem, when you had two or three games where [you had problems] – he wasn’t gonna throw you out there again to save the game. One time, yeah; two times, maybe.

I don’t think I ever had that problem then; but everybody has bad stretches. But I guess mine weren’t bad enough where he took me out of the closer’s role, because I was always his closer.

JH: 1974 was the year you had 12 saves: all of the saves the Rangers had that season.

F: Yeah! But what that doesn’t tell you is how many times he would bring me into the game in the sixth inning, when we were winning 7-2. Or the eighth inning when we were winning, because he didn’t trust anyone else to pitch when we were winning the game. So you don’t get a save, but you finished the game. I probably finished 25 other games that we won that were not save situations.

[Fookie had 53 Games Finished in 1974, with 12 saves and 144.1 Innings Pitched in 69 appearances.]

JH: You averaged 2+ innings per appearance; unheard-of today. Was your arm hanging by the end of the year?

F: Well, it was always sore. When your arm was sore, you could tell, because you could look down at your bicep muscle, and you could see your heart beating in it. It wasn’t painful, just sore. And that was from pitching a lot.

But back then, you had to pitch when your arm was tired. That’s just the way it was, because there were only five of you in the bullpen. If the starting pitcher has a bad game two days in a row, that’s pretty hard on the bullpen with five guys out there!

Nowadays, they’d have to call up twelve guys from the minor leagues to take that load [laughs].

JH: When you hit the end of a season like that, what did you do for your arm?

F: Nothing. Fish and golf. And drink plenty of beer.

JH: A rigorous rehab program, in other words!

F: From October to December, you drank a lot of beer and ate a lot of hamburgers and stuff like that. There wasn’t a lot of going to the gym and working out, and that kind of stuff. Right after New Year’s is when you started getting ready for spring training. So that’s about four or five weeks [where] you started going to the park and running and playing catch, stuff like that.

Momentous meeting: Chicki and Fookie

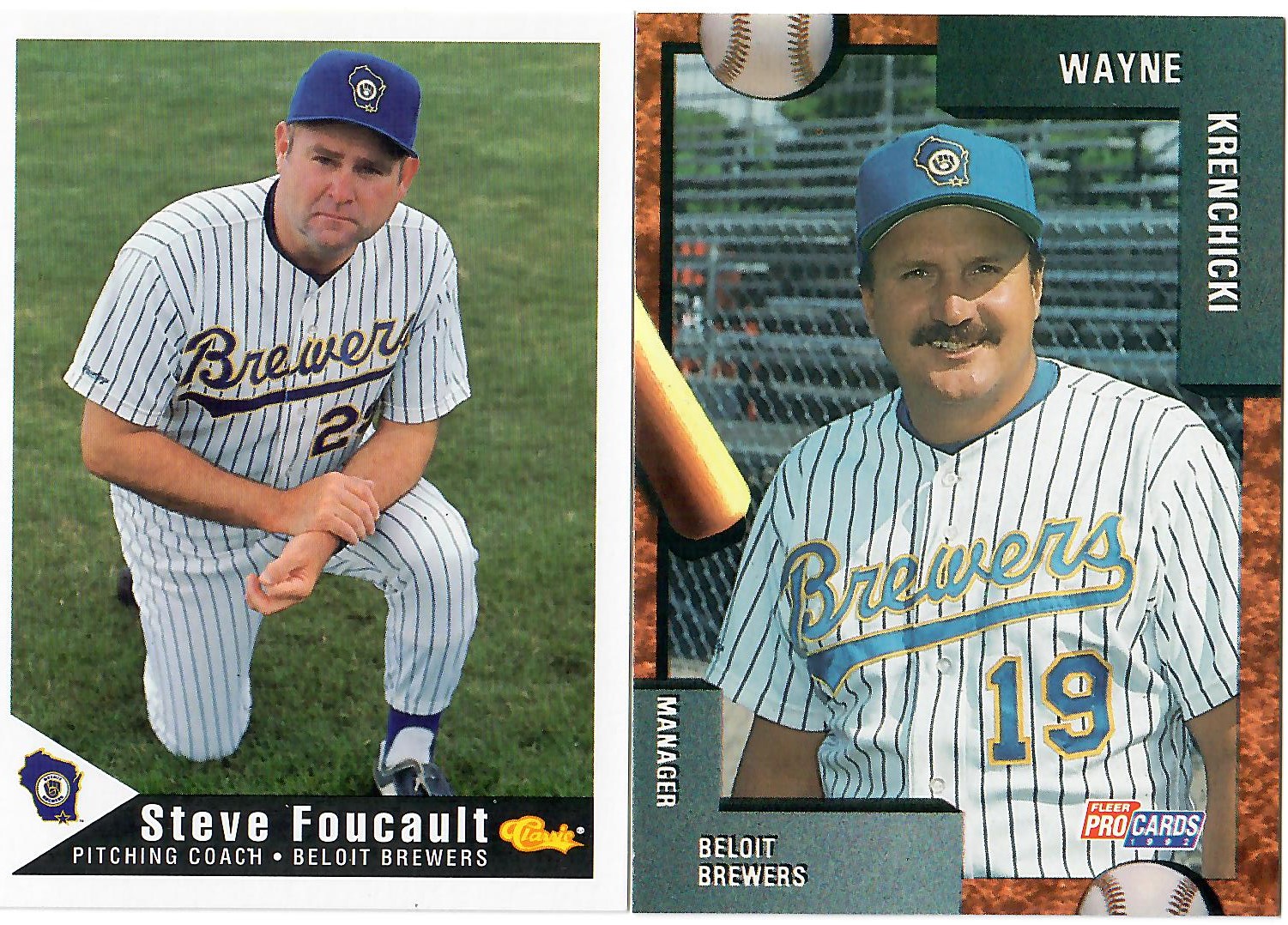

JH: And you pitched batting practice to one Wayne Krenchicki [8-year MLB veteran who later managed several clubs with Fookie as pitching coach] in 1975.

F: I did, at the University of Miami. I would go to my old high school, too, and throw batting practice there, and I would go to Miami-Dade South, because I knew the coaches down there.

JH: When you do something like that, and you know you’re getting ready for the season, are you just throwing BP speed, just trying to get your arm loose?

F: Pretty much. It was for the benefit of just being on the mound and pitching. Usually, before I would throw the BP for those guys, or after, I’d get a catcher in the bullpen and I would throw 20-30 pitches at game-type speed.

JH: Did that give you a leg up in spring training — that you were ready? Or was that more normal that a relief pitcher would be more ready to go, and they wouldn’t have to work their way in? Targeting the first of April?

F: Yeah. Nowadays, when guys come to spring training, they’re ready to pitch in a game. Back then, I probably was [ready] because I lived in Florida for a couple of those years; you could go outside and do whatever you wanted year ‘round. People who lived up North didn’t have that luxury.

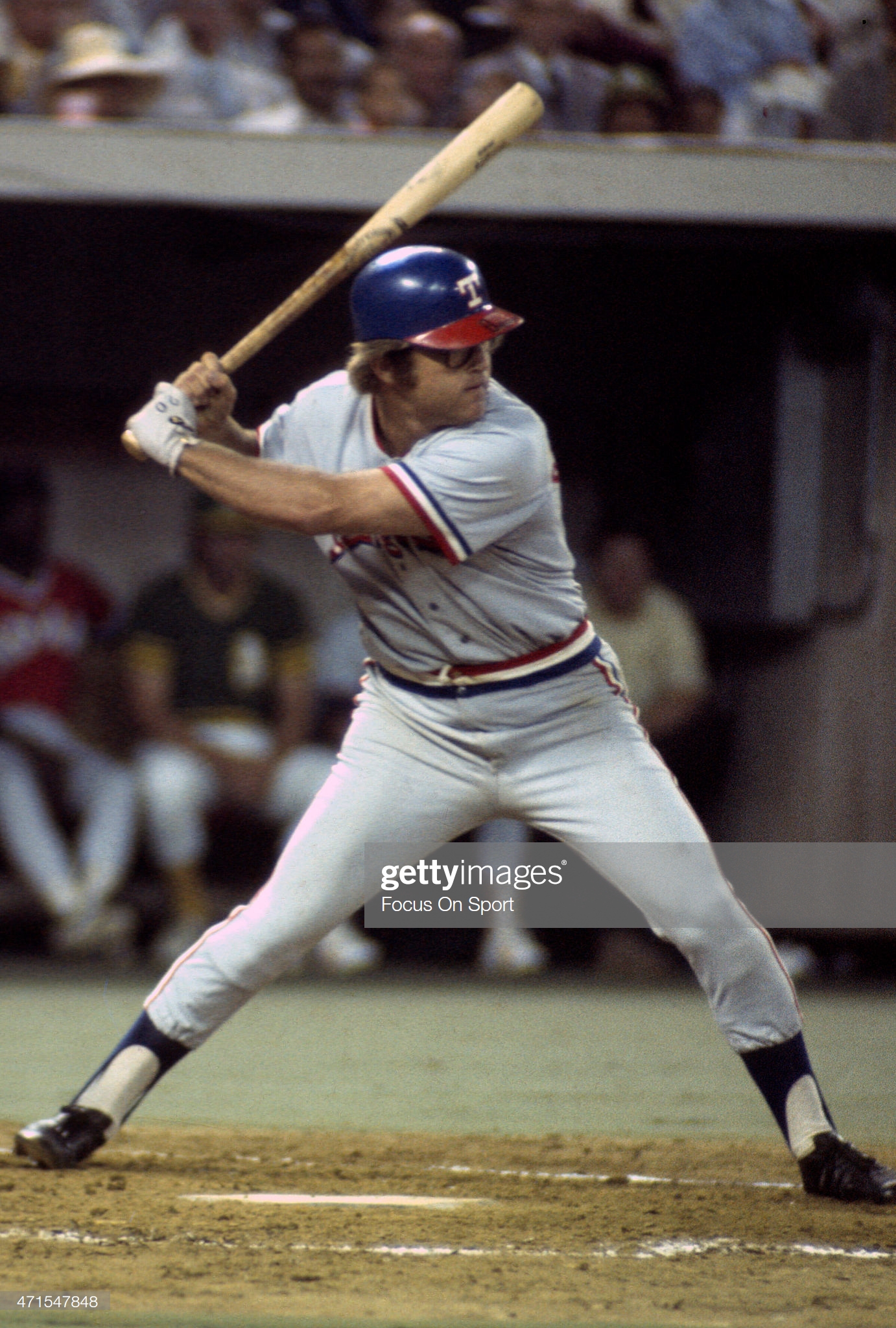

The 1974 Rangers were a fun team to watch, because they were not competitive the first two season in Texas. Now they were giving Oakland all they could handle.

JH: 1974 was such a significant year for the whole Rangers franchise.

F: Yes, it was.

JH: What made that team kind of gel to the point where you were competitive all the time, and gave Oakland such a hard time? Can you put your finger on anything, looking back?

F: We had enough veteran players, and the younger players were playing well, and weren’t intimidated by [Oakland stars] Gene Tenace and Reggie Jackson and Joe Rudi and Catfish Hunter. We took it as a challenge, and we beat the piss out of them a lot of times [the Rangers finished 10-8 vs Oakland in 1974].

JH: This was the time of [Mike] Hargrove coming up, and [Jim] Sundberg.

F: Tom Grieve was playing well; Jeff Burroughs had an MVP season. Fergie Jenkins was Comeback Player of the Year, and won 25 games. Jim Bibby won 19 games [and lost 19; an astonishing 38 decisions in 41 starts!]. We had starting pitchers who threw complete games. A few guys, you couldn’t get them off the mound until the game was over. That was their job: to pitch nine innings.

1975: Great Expectations and a fall to earth

JH: You’ve given Oakland a run for the money; the guys have all gotten another year of experience. It’s a mixture of old guys and young guys. And I remember clearly that there were a lot bigger expectations, all of a sudden. The Rangers went from being –

F: The laughingstock?

JH: Well, for a lot of fans, they were the team everybody else played – they were fans of other teams, like the Cardinals or Yankees. They would draw like crazy when the Yankees came to town, or Oakland, but a lot of times, the other teams were the headliners. Now, all of a sudden, after 1974, “wait a minute! This is a different deal!”

So how did the wheels come off in 1975? Billy Martin is still there, but that’s his last season there.

F: I don’t know; things just didn’t go like they did the year before. You don’t like to blame anybody, because everyone has a part in it. It probably starts with the manager and goes from there, you know?

JH: Martin had this history of being a hard-driving guy. After his second or third season in a place, it seemed like things turned around –

F: He would wear his welcome out.

JH: Was that with the players, as well as front-office people, and like that? Was he a tough guy to play for, as much as we have heard that?

F: Yes, he was very hard to play for. That’s why I say, when you were playing well, he was your best buddy. And when you were not playing so well, he was – he wouldn’t even say hello to you. He’d walk right by you, without even acknowledging that you were there.

And that’s kind of hard to deal with, as a major-league player.

JH: And especially a young player, probably.

F: Yes. I mean, that’s not how you would treat anybody, much less one of your players.

JH: Do you think he was especially tough on the pitchers?

F: Probably more so than the everyday players, yeah.

JH: Do you think he knew pitching? Did he understand pitching?

F: To a certain point he did, yeah. He did. But he probably thought he knew a lot more than he actually did; at least, it came across that way. Because when he came out to the mound, it wasn’t always to take you out. He didn’t always send [pitching coach] Art Fowler out there.

Sometimes Billy would come out and he would give you exact instructions of what to do, and they needed to be followed to a T. If they weren’t, and you did something other than what you were told to do to a particular hitter, and something bad happened, he probably wouldn’t have spoken to you for a month.

So you pretty much did what he said. If it worked out, great. If it didn’t work out, “hey, it’s not my fault. This is what I was told to do.” Made a bad pitch; it happens.

JH: How much of the pitching staff was Fowler’s real responsibility? There’s always this perception that he was there because he was Martin’s drinking buddy. Was he legit in his role, running the pitching staff?

F: He was good at what he did. Part of it was what you said about being Billy’s drinking buddy; Billy liked to have people around him that he could kind of boss around, and they looked at him as, like, the CEO. But Art kept it light; when he came out to the mound, he always wanted to get you to laugh. And he had some classic sayings when he came out to the mound, I can tell you that!

JH: Would you care to elaborate on any of those?

F: Well, Art and Billy are no longer with us, so we can’t embarrass them or make them feel bad, if they happen to see or hear an interview. But …

In Denver in 1972, Fowler still pitched once in a while! He was like 55 years old and had a glass eye. He could hardly walk, but he could still pitch!

[In 1970, Fowler was 9-5 with a 1.59 ERA in AAA – at age 47!]

One day, maybe 1974, we were winning the game, but I was having a hard time; walked a couple guys or something. There were two out, and Art walked out and said, “Well, Fookie, you’re starting to create a pretty good mess here. We need to change that right now. You better get the next guy out, or Billy Martin is gonna kill me.” And he turned around and walked away.

You had to laugh, because it was pretty funny, and he had a way of saying it that kind of loosened you up. And I got the next guy out.

He never chewed you out; he kept it light. But he had a message every time he came out there.

More change for the Rangers: Martin out, Lucchesi in

The success of 1974 was not sustainable in 1975, and as was Billy Martin’s pattern as a manger, things went downhill quickly when the team began losing. Martin was fired July 20, 1975.

JH: By that point, was everybody ready for a change?

F: I think so. The clubhouse wasn’t the same in 1975. It wasn’t like the Oakland clubhouse, where guys were beating each other up every other night, but it just didn’t feel the same, for whatever reason.

JH: How was the approach and attitude right after Martin was gone?

F: Well, Frank Lucchesi came in. And Frank was a players’ manager. He was like your

next-door neighbor; an awesome guy. Fun to play for, and just a good guy; you wanted to play well for him.

JH: As long as you keep him away from Lenny Randle!

F: Yeah! Exactly!

[Randle decked Lucchesi on the field during spring training 1977.]

JH: Lucchesi kind of gave you guys your own head, and let you –

F: Yeah, kind of just let us play. Gave us a little direction. Wasn’t a whole lot of rules and regulations, like the other manager had.

1977: Traded to Detroit

I was traded a week into the 1977 season, and I don’t remember if Frank was still manager then [he was]. Because when I got traded [4/12/77, to the Tigers, for Willie Horton] Frank was sad to see me go. He didn’t have anything to do with me being traded; it wasn’t his idea.

manager then [he was]. Because when I got traded [4/12/77, to the Tigers, for Willie Horton] Frank was sad to see me go. He didn’t have anything to do with me being traded; it wasn’t his idea.

JH: Did they just feel that they needed Horton’s bat so bad, or — ?

F: I don’t know. I really don’t.

What happened was, they traded Jeff Burroughs to Atlanta, and they brought in a bunch of Braves people.

JH: Adrian Devine, and that bunch?

F: Yeah. But he lasted about a year. Then Kernie [Jim Kern] was the next guy.

JH: So you headed to Detroit, and do I understand correctly that some of the people there were not exactly thrilled that Horton was gone, and you were there?

F: Yeah, but they didn’t treat me badly; you just read that in the papers. The people in the stands didn’t boo me, or that stuff.

JH: Were you the closer right away, for the Tigers?

F: Pretty much, yeah. John Hiller was there, but John was at the end of his career. His career maybe should have been over before then, but John was a hero in Detroit: all the saves and all the pitching he had done for that team. And he was with the World Series team in 1968.

John became my best friend on that team.

JH: So there wasn’t any issue between you guys over who had what role?

F: Oh, no! John never said anything to me about taking his job, or anything like that. I didn’t take his job; they gave it to me. It wasn’t my fault!

And I pitched well for them.

JH: So pitching in Detroit and for Detroit – that was OK?

F: Yeah! They had a few veterans on the team, and they were – most of the guys on that team in 1977 and 1978 were younger than I was. That was “the young and up-and-coming stars of the Detroit Tigers,” and they were. And they ended up as pretty dang good players!

JH: Was this when Fetzer and those guys were in charge?

Teammates with Tweety: Fidrych mania

F: John Fetzer was the owner, yes. Mark Fidrych was pitching there, and –

JH: What was that like, dealing with – because you were there after his debut [in 1976]?

F: He was still good in 1977. But he got hurt.

JH: He got hurt in spring training, then came back and was OK for a while, then hurt his shoulder. They found out years later that it was a rotator-cuff thing.

What was it like, dealing with all that hoopla around him?

F: It was awesome! That guy was the greatest guy. He was just like your childhood friend when you were ten years old. He was like a little kid. He had more fun – that’s the way he approached the game: like he was playing with the neighborhood kids.

He had more fun pitching than anybody I ever watched, I think. And he was real good at it, too!

I remember the first day I was there. I met the team in Toronto, but he didn’t pitch there; he was pitching the first game back in Detroit. And John Hiller told me in the bullpen – their bullpen was like a dungeon; it was underground, and your head was sticking about two inches above ground level, and it was very small — and John sat down next to me and said, “Fookie, sit down and enjoy the game, because you’re not pitching in this game. That curly-headed guy is pitching nine innings.”

So I just got comfortable, and John and I watched the game and talked. When it was over, John said, “come on down to the dugout with me. I want you to watch this.” And he told me exactly what was going to happen. I called Fidrych “Tweety.” People called him “Bird,” but I called him Tweety, and he loved it.

John said:

“Bird’s gonna go inside, and he’s gonna take his jersey off, and he’s gonna pound about two Stroh’s [beer] in about three minutes, and get his head all wet under the faucet, and get all those curly locks all wet, and he’s gonna come out in his soaking-wet sleeves [baseball undershirt] and he’s gonna take a lap around the warning track. But he’ll wait about ten minutes. The people will be in a frenzy.”

And as soon as the game was over, and he walked into the tunnel, the people started screaming, “we want The Bird! We want The Bird!” And it went on for like, ten minutes.

And he pounded his first beer, and I looked over in the corner, and the people couldn’t see him, but I could see he had the other beer in his hand. He pounded that one down, walked out on the field, and started jogging around the warning track. He did that, went back in the clubhouse, and then people started to leave!

Tweety was really good.

Shoulder injury

JH: Did you hurt your arm in Detroit?

F: Actually, I hurt it in spring training when I was with the Rangers, before I got traded. But you can’t say anything. You couldn’t, or you wouldn’t have a job.

JH: Was it a particular pitch? Could you feel it pop?

F: It was on a pitch; it didn’t pop, but it hurt. I could still throw hard, and I could still pitch, but I used to be able to get warmed up to pitch in, like, ten pitches. Now it took about 30. But I could still pitch. It was probably a rotator cuff, but … you deal with the pain, and do the best you can.

I still did pretty good after that, for two years [laughs]. It wasn’t great, but I was still pretty good.

JH: So you’re dealing with a bum arm from that point on.

F: Pretty much, yeah.

1978: A coin flip and Kansas City

JH: And you said it was OK to pitch in Detroit. How did things get to the point where you end up going to Kansas City? What changed?

F: The next year (1979) I would have been a free agent. The people in Detroit didn’t like to pay anybody. No one made any money playing for Detroit then. But I was still pitching pretty good. Sometime in August 1978, I guess they decided they weren’t going to have me around [for 1979], so they put me on waivers.

Two teams claimed me: the Brewers and the Royals. Whitey Herzog was Kansas City’s manager, so that’s part of the reason. And I didn’t know anybody with the Brewers at the time. But I always pitched good against Milwaukee.

I don’t know this as a fact, but I heard later that both teams had the same record at the time [waiver claims are awarded in reverse order of the standings]. I heard there was a coin flip in Kansas City – true or not, I can’t tell you. We may never know. But it made a lot of sense to me.

That’s how I got to Kansas City.

JH: But only three games for them, and you weren’t put on the postseason roster, because they wanted Steve Busby on there?

F: Whitey called me into the office. Here we go again, I thought. This is getting to be a habit.

He says, “well, Fookie, I got some bad news for you.” I knew what was going on. “We have to have our playoff roster set, and Steve Busby’s been injured, and he’s ready to come back. He might not be ready to pitch, but he’s been here a long time,” and I guess they figured they owed him that. “You were the last one here, so you’ll have to be the first one to go.”

So that was it. Got in my truck and went home to Arlington.

1979: No thanks to Japan, and spring training with the Mariners

JH: So over the winter, did you get feelers? You did try to come back.

F: My agent was from IMG, out of Cleveland. Mike Hargrove got me introduced to them. They actually had me a job; I could have gone to Japan to pitch. But I didn’t like that idea. I wasn’t a big fan of traveling then, and I’m still not!

So I ended up getting an invitation to spring training with the Mariners. I went to Arizona, and I was there up until about ten days left in spring training. I was doing OK; I wasn’t fabulous or anything.

But there were a lot of guys there like myself – Paul Lindblad, Dick Pole, maybe Tom House. The manager [Darrell Johnson] goes, “Fookie, we’re going with all the young players, and all the young pitchers. We may get our ass handed to us more nights than not.”

And they released all of us: Lindblad, Dick Pole — there were five or six of us. So we all left.

The Astros: insurance policy, and the end of the line

Larry Hardy, my buddy from Arlington who I played winter ball with and owned a batting range with in later years, called me up and says, “Fookie, I can get you a job here with the Astros.” Larry was a AAA player-coach. Still pitched a little bit when they needed pitching.

So I said, “OK, I’ll try that.” And he called me the next day and said, “come on over.” So I got in my truck and drove to Cocoa, where the Astros trained. I ended up living about five miles from that place, years later.

I was there for about ten days, went to their camp, and went to AAA with them. The reason they kept me was, Joe Sambito was their new closer, and he was a rookie. They didn’t now how he was gonna work out. So I was with them for probably three or four weeks. Fished a little bit. Pitched OK, but about a month later, the manager calls me into his office again [laughs]. The manager was Jim Beauchamp – good guy. An old Atlanta Braves guy.

He said, “well, Fookie, here are my instructions to you from the office: Joe’s actually doing a pretty good job in the big leagues. You were brought in here for an insurance policy, if something happened to Joe, or Joe didn’t perform. They feel like he’s gonna be OK, so we’re gonna let you go. It wasn’t my idea; it was theirs.”

I said, “I understand.” I wanted to say, “I’ve heard that a lot the last couple of years,” but I didn’t.

So I went home and I said, “that’s enough of this shit.” I pretty much said, “I’m done. I’m not gonna play anymore.” I got tired of all that crap.

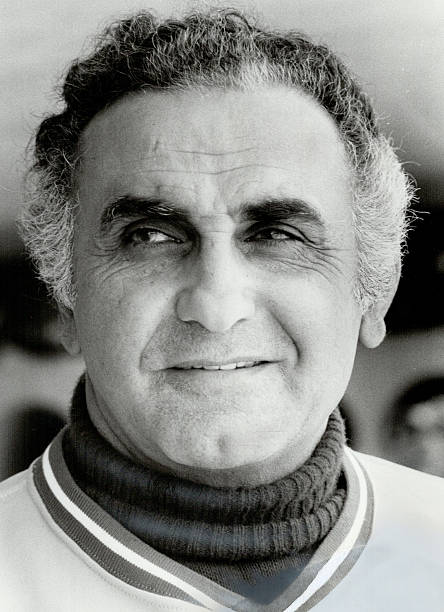

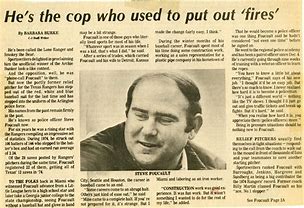

Police Academy

So I sat around for a little while. My ex-wife had become friends with this police lieutenant and his wife. Really nice people, and we had dinner with them one night, and the guy said, “why don’t you go to the police academy, and become a cop? It’s a great job, with great benefits. I know it’s not quite what you’re used to.”

So I thought, “OK,” and that’s how I ended up going to the police academy. I was the  vice-president of the class, and all that stuff. It was a lot of fun, it really was.

vice-president of the class, and all that stuff. It was a lot of fun, it really was.

There were about 40 people in our class, and maybe ten from Arlington. It was called the North Texas Congress of Governments Police Academy, or something like that. Probably ten cities had future policemen at the Academy. I think it lasted about six months.

I was a cop for five years; it was a fun job.

Finding the Range

JH: What led to the end of the police work?

F: Larry Hardy wanted to open up an indoor batting range in Euless, Texas. He wanted me to become his partner, though I was still a cop. Things weren’t going so great at home, either, at the time.

So I ended up putting up some money, and we opened the batting range. I tried to do both jobs at the same time, but it ended up being way too much. I couldn’t do both, so I had to make a decision. Larry was giving some lessons up there in the wintertime, and we built an indoor mound and stuff. Had softball cages and baseball batting cages.

I watched Larry a lot, and learned from him about pitching mechanics and things like that; I knew how to pitch, but not how to teach it; I was never taught anything.

So I ended up quitting the police department, and I ran the batting range. I was there most of the time, but we did have a couple of young kids who worked there for us, because it got busy a lot of times.

That lasted a couple of years, and then it got to where it became pretty seasonal, and Larry decided it was time to pull the plug on that. So that became history, and actually some guy from Carrollton bought it from us. They had to tear all of the equipment down, and put it on a big tractor-trailer and move it to Carrollton.

But when the guy bought it, he wanted me to come to Carrollton and help them get started. Teach some lessons there, and stuff like that. I didn’t have to do it, but meantime I had gotten divorced, and so I was single and had an apartment. I met a guy there, Jerry, and became really good friends with him. He said, “Why don’t you come over and live in my house? Let me talk to my wife.” So he talked to his wife, and she said, “OK, for a few months,” so I lived there for a while. It was five minutes from the batting cages.

Jerry had become like a father to two young boys, maybe 10 and 12, who were really good players. He would bring them there almost every day. I was teaching these kids for free, because they were friends of Jerry’s.

After that, I became security director at the Arlington Sheraton for a year. I did baseball lessons, and eventually my buddy Larry came into play again.

Back in the game with the Brewers

Larry called and said, “Fookie, I’ve got a friend who’s involved with the Brewers’ minor- league system as Field Coordinator. I’m gonna talk to him and see if I can get you a job.”

league system as Field Coordinator. I’m gonna talk to him and see if I can get you a job.”

So my phone rings one day, and it’s this guy he was talking about: Bob Humphreys. We talked, and I got a job on the phone right there!

I had a couple of months left before I had to go to Arizona for spring training, and that’s how I met Krenchicki, was through this job. Then I got another call, and Humphreys said, “Fookie, something’s happened. You’re not going to Rookie League; you’re going to Beloit, Wisconsin. You’ll be going to a full-season, Class A team. Instead of making $15,000, you’ll make $28,000.”

Almost doubled my salary, and I hadn’t done anything!

I’m thinking, this is awesome! And Krenchicki was the manager at Beloit, so I became Wayne Krenchicki’s pitching coach.

JH: A match made in heaven!

F: Unbelievable!

JH: How did the working relationship between the two of you evolve? Did you have to kind of feel each other out on that?

F: No, because we had that connection from when he went to school at Miami, and I grew up in Miami. Remember, I had thrown batting practice to him many years earlier. So we did know each other, but we didn’t really know each other. So we got along great. We had a hell of a time together.

After three years, they decided we were having too much fun, I guess, and we were too good with the players. So they fired us. Called us into the office again! [laughs]

JH: Did they ever say specifically what the issue was, or “we’re going in another direction?”

F: No. “We’re going in another direction.” But that’s not the direction I’m going!

1995-1996: Back with the Rangers

So we were both looking for jobs at that time, and I sent out resumés, and the Rangers hired me to be a pitching coach. So I’m going to spring training with the Rangers in 1995. I got married on March 3, 1995, and the next day we drove across Florida to spring training.

JH: Some honeymoon!

F: Yeah! My wife was still working down in Miami Beach at the time. After we got married, she worked through that summer, or part of it anyhow. She eventually retired and moved to Port Charlotte for the rest of the summer (I was working in Rookie League there).

The next year, I was with Bump Wills in the New York-Penn league. We packed up the little Honda Civic and drove to Poughkeepsie, New York, to be with Bump Wills. Finished that year out, and the next year I was with Butch Wynegar in Port Charlotte in the Florida State League.

“We’re not gonna bring you back.”

The farm director, Reid Nichols, came to town in August, and called me in for a meeting. Here we go again!

“Fookie, I want to talk to you about next year. We’re not gonna bring you back. The pitchers aren’t doing what they’re supposed to be doing.”

We were at a huge conference table; 15 chairs on each side. Not one time in our conversation did he ever look at me. No eye contact. I was looking at him, but he wasn’t looking at me.

I said, “Reid, I’m not sure who you’re getting your information from, but that’s a bowl of you-know-what. I’m here at this ballpark, when it’s almost 100 degrees, every day, at noon. I’m running, and lifting weights, and all my pitchers are here by 1:00. And they’re doing their work, because I’m done with mine, and I’m watching them. I know what they do and what they don’t do.”

“Well, I’m just telling you the information that I got.” And he goes, “You’re not coming back next year. You need to write all of your reports. If you don’t write all of your reports, you’re not gonna get your last paycheck.”

Now I’m fuming. I’m seriously pissed. I’m gonna do the reports; I don’t want to miss a paycheck. And they fired Steve Luebber, too, the same time they did me. And he was the pitching coordinator.

And the reason we got fired was, Dan Kolb was one of my pitchers. And the year before, he was Pitcher of the Year in the entire minor leagues, maybe. He was just fabulous. So he comes to me in 1997, and he pitches like garbage. He can’t throw the ball over the plate; he’s not doing anything. This went on the whole year.

And so one of my other pitchers – who will remain nameless – when I made the announcement after Reid told me that day, and I told my pitchers I wasn’t coming back – one guy walked up to me, my favorite pitcher on the staff, and goes, “I know why you got fired. Dan Kolb’s pitching like shit.”

I said, “it could be. But probably not.” And I knew it was the reason, but I never acknowledged that fact to the pitchers; that’s not the way you’re supposed to do things.

And he said, “I know it is.”

I said, “OK, whatever you say.”

So I finished that out, and Krenchicki got a job in the Atlantic League, so he and I got hooked up again, in Lehigh Valley. We were together for the next 13 years, on five different teams. And we were very successful.

JH: Did your experience as a coach in Organized Ball help you when you got to independent ball, or did you have to adjust your approach to deal with independent players, who have a different agenda than Organized Ball players?

F: Well, the players we got were in the same boat as I was: they weren’t wanted by anybody.

JH: They had been released, and were looking for another chance?

F: Right. They weren’t given the chance, and most of them really took to coaching; they wanted to get better. I’m sure I helped some of them, and some I probably didn’t. But that’s the way it is with everything.

You do your best to help everybody.

But the independent thing is, you didn’t have the #1 draft picks, and the guys you had to baby and pamper and all that crap. Those are the guys who were the most pains-in-the-asses. They already think they know everything anyhow, so they really don’t want to listen a whole lot. [Or] They listen but they don’t really hear what you’re saying.

JH: Do you think you were the same type of pitching coach, as far as how you worked with the players, in independent ball? Did you evolve how you taught pitchers, and how you worked with them?

F: Kind of, yeah. You learn as a player learns, from your experiences. And the longer you coach, if you’re willing to listen to other people, what they do – that’s why I still watch baseball games today. I learn something almost every time I watch a baseball game. And that’s what the game is about. But a lot of kids today don’t watch baseball games on TV, so they don’t learn; they don’t know anything about the game.

You can coach until you’re blue in the face, but until they’re on the field and they hear and see what it’s supposed to look like, it’s a struggle for them.

JH: I heard [San Antonio Spurs coach] Gregg Popovich say, “the players have to allow you to coach them. If they don’t, it doesn’t matter.” Would you describe yourself as a “feel” guy, or a “mechanics” guy, a size-up-the-situation kind of guy?

F: I was not a guy who was gonna sit down with a pitcher every inning and talk about every pitch they threw, and “why did you do this?” and “why did you do that?” They learn through experience – the mistakes that they make. And if they don’t correct those mistakes, they’re not going to get any better.

So when a guy threw in the bullpen, and I was the pitching coach, I watched him every time he threw; they didn’t throw in the bullpen without me being there. I just wanted to watch them – what they did – all of the time. Because if they did something different, and they were having a hard time, now I knew what it was, because I watched them pitch every day.

Throwing in the bullpen is where you develop your habits – good or bad.

A lot of guys can do what you tell them in the bullpen, but they can’t do it on the mound, because there’s too much pressure and too much going on. They’re thinking too much, and they’re not able to do what they did in the bullpen. And that takes a long time to develop.

JH: So you were basically looking for keys to that pitcher – his delivery?

F: Yeah. What he did all the time.

JH: And when you see him stray from that, that’s when you’re going to the mound, or talking to him and saying, “hey, I see this or that”?

F: Right.

“Do you know you’re doing this?”

“No, sir. I don’t know I’m doing that.”

JH: Did you find consistent problems – issues – with those young pitchers in independent ball? Did they tend to make the same kinds of mistakes, because they either weren’t coached right or didn’t develop correctly?

F: They were all different, because they’ve all had different coaches in different organizations who stressed different things.

Some guys, it doesn’t matter who coaches them; they’re gonna get to the big leagues. You could put your little sister out there as the pitching coach, and that guy’s gonna get to the big leagues, because he has ability other people don’t have.

Then you have a guy who was a 50th-round draft pick, or a free agent. He wasn’t really great in college, or whatever, and he has that Eureka! moment, where something happens. All of a sudden you’re saying, “who’s that guy?” He just becomes a good pitcher. Strange how that happens.

Disaster in Evansville and success in Long Island: There “Otter” be a law

In 2009, the Krenchicki-Foucault tandem’s next stop was in Evansville, Indiana with the Otters in the independent Frontier League. It did not go well. It was a step down, talentwise, from the Atlantic League, and my friends were saddled with ownership that was essentially clueless about how to operate a winning club. After a little more than 1-1/2 seasons, they parted ways. That was Krenchicki’s final stop as a manager, but Fookie still had some baseball left in him, so he went to the Long Island Ducks of the Atlantic League for several seasons.

JH: So you finish up your “glorious” time at Evansville, and head to Long Island. You had a lot of success there. Was it just a better situation? And you were even better as a pitching coach? How did those Long Island years work out?

pitching coach? How did those Long Island years work out?

F: They ended up being terrific! Kevin Baez was the manager; they had just named him the manager when I got there. He had never managed before, anywhere. He had been a base coach and a player-coach for a few years. Then they fired the manager and promoted him, so they wanted to hire an experienced pitching coach, because he had never done that. The hardest thing a manager has to do is to manage his pitching staff, and I was available.

Long Island was great because Kevin said, “Fookie, the pitching staff is yours. Do whatever you want to do with them. I’ll take the pitchers out of the game; you tell me when to take them out, and why.”

I said, “OK, I’ll do that for a couple of months, but you’re the manager. You need to learn how to do that yourself. The first few months, I’ll do it and tell you why. After that, you’re doing it. If I keep doing it, you’ll never learn how to do it yourself.”

So we were pretty good, and after a couple of months, he started [making the changes]. But he would still ask me, “did I do the right thing?” And I told him:

If you think you did the right thing, you did the right thing. All you gotta do is please yourself. Don’t let what happens – if a guy [messes] it up – change your decision, because you did what you thought was right at the time. It doesn’t always turn out right. That’s why you’re the manager, and you get paid. If you make the wrong decisions too often, that’s why managers get fired.

It turned out good, and we did have good players in Long Island. Long Island has a lot of money, and they always had good players. We didn’t get to keep them all the time, because they got picked up by organizations, but we always had good players.

We had several players who had played in the big leagues for 8-10 years, who wanted to keep playing. The people in Long Island liked the big-name players, because they brought people into the ballpark.

JH: Butts in seats!

F: Yeah! I had known Buddy Harrelson [ex-MLB player and a coach/owner with the Ducks], because I had coached in the Atlantic League for so long. He let me stay at his house when I coached there. He wouldn’t even let me pay him rent. But he loved Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, so I made sure he had plenty of that every night. He would come back after a game, sit in his recliner, pop on SportsCenter, and eat a pint of Ben & Jerry’s. Every night!

JH: Long Island “worked” for several years for you. But what happened? You finally just got tired of it all?

F: I got tired of sitting on that hard-ass bus! Every road trip from Long Island was pretty – not real far, but it took a long time to get there, because you had to go through the city to get anywhere, except for Bridgeport; we rode a ferry there.

And I said to myself, “I’ll be 65 a month after this season ends. I think I’ve had enough.” And I’m perfectly good with that.

JH: No regrets?

F: No regrets at all. None.

JH: Don’t miss the game?

F: Not particularly, no. I watch a lot of games.

JH: Satisfied with your own playing career?

[a long pause]

JH: You probably wish it could have been longer, I guess.

F: Yeah. My goal was ten years, but I didn’t make it because of my shoulder injury. And that’s fine.

JH: Did you ever get the shoulder fixed?

F: No. But it still works; I threw batting practice for 25 years. It doesn’t affect me physically; I can do anything I want to. My knees, though are another story [laughs].

Thanks to Steve for taking the time to do this interview, and for many years of great memories — on and off the field.