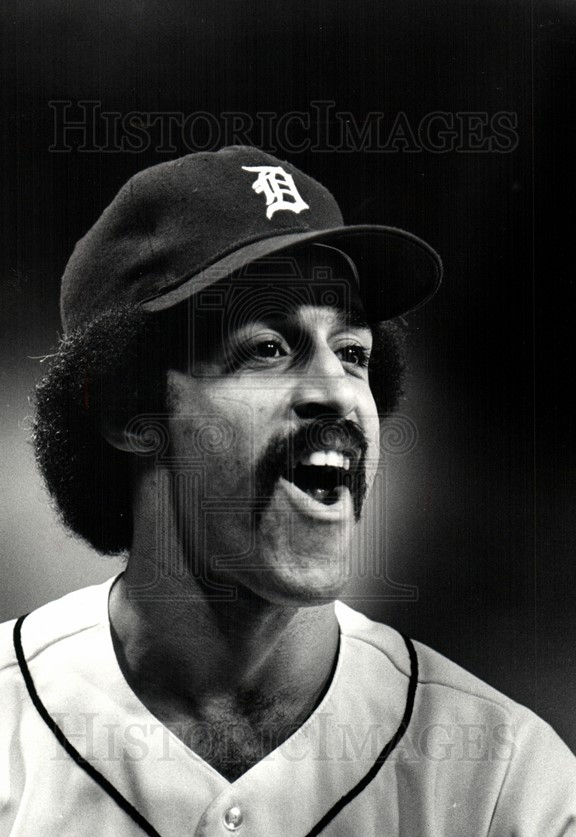

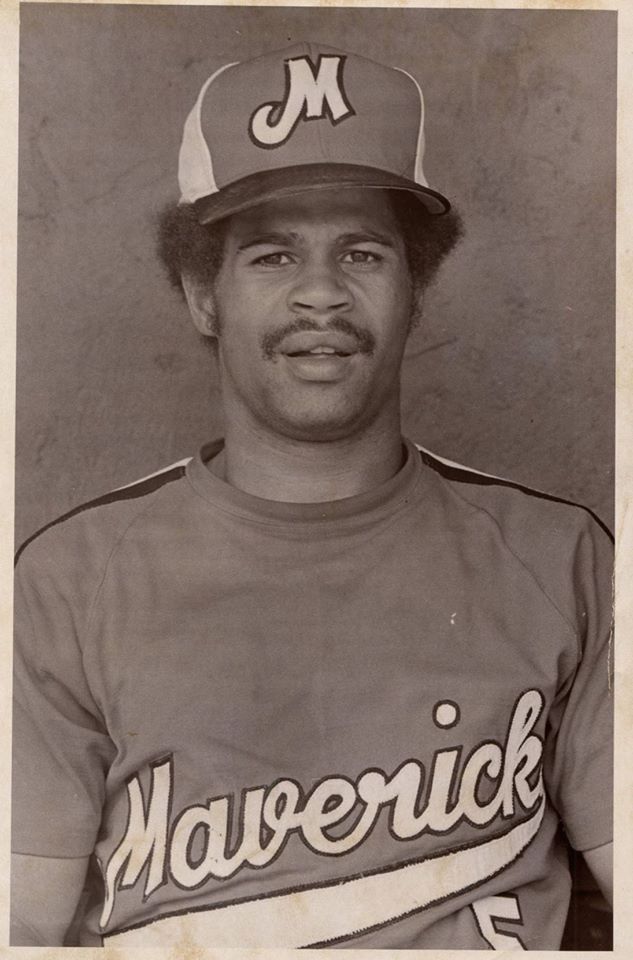

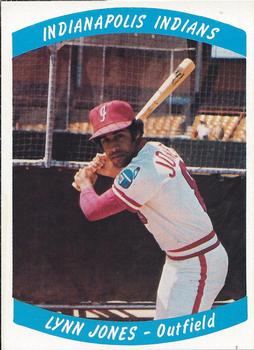

Lynn Jones was a tenth-round draft pick of the Reds in 1974. He was a key member of the 1975 Eugene Emeralds championship team, and he later won World Series rings with Kansas City as a player and the Red Sox as a coach. He played in the big leagues from 1979-1986, and would have had a longer big-league career had he not been “blocked” by the talent in the Reds’ organization during the mid-1970s.

1975 Eugene Emeralds championship team, and he later won World Series rings with Kansas City as a player and the Red Sox as a coach. He played in the big leagues from 1979-1986, and would have had a longer big-league career had he not been “blocked” by the talent in the Reds’ organization during the mid-1970s.

Still, he was great fondness for his time in the Reds’ organization, and particularly for Eugene manager Greg Riddoch.

Excerpted from my book The Little Red Wagon: The 1975 Eugene Emeralds.

Lynn Jones I live north of Pittsburgh, and we’re 350 people. And do you know the movie Sandlot? We lived it. We lived that.

We didn’t have a movie theater. We didn’t have a swimming pool. We played Wiffle ball nine hours a day, and when we were through playing Wiffle ball, we’d put our uniforms on and went and played Little League, Bantam League, Babe Ruth, Legion. That’s what we did.

And my Dad was our coach for Little League and Bantam League and Babe Ruth and Legion. And we had the baseball field right beside our house. So we turned the field around and played Wiffle ball from second base out. So we had a fence, and that’s what we did. And when we were done playing that, we were going down to the creek, and fish and swim and come back.

And, you know, this was every day: we lived Sandlot.

Jim Haught Was baseball always your game? Did you play other sports as well?

LJ Actually, I went to school to play basketball. I was a guard, and I went to school down at Thiel College.

JH How did baseball figure into that, if you were hooping all the time?

LJ I played soccer in the fall, and soccer was something you played to get in shape to play basketball. And once basketball was over, you could go into baseball, because it’s not like now, where coaches and parents, they want you to specialize in one sport; we played all the sports back then. And so if you could play two sports, three sports, you did — as long as you could maintain your grades.

JH Were you scouted heavily?

LJ No. As a matter of fact, I didn’t know whether I was going to be scouted. I went down and played in the summer college league because I didn’t want to work. I didn’t want to have to go through working another job in a factory. So I went down there and my brother hooked me up with my team, and we just played. But you know, with limited at-bats, I didn’t think I was really being scouted.

Elmer Gray is the one who signed me, and scouted me. So he must have also followed me, and followed my playing up at Thiel, and saw me up there.

For the amount of playing time that I got, between there and playing only 16 games or 18 games a year in at Thiel College because of the weather, and getting drafted — I think it was in the 11th round — that’s not bad.

JH Tenth round in 1974. And your signing bonus was probably a yearbook and a plane ticket?

LJ I had to negotiate up from $500 to $1,000.

JH Hey, you did pretty good, for those days, for a 10th-round pick! [laughter]

LJ I remember we were all sitting, our first day at rookie league in Billings, Montana. I met Steve Henderson, Danny Norman Mike Grace, Donny Lau. Mike LaCoss, I think he was a number-two pick. [#3]

We were all in a room, and Steve Reed was the number-one pick. And he made a statement — because he was the number-one pick — he said, man, I’ll probably be in the big leagues in a couple of years. And we looked at him and it was like, really? You haven’t even been out on the field yet! And he already made the statement he was probably going to be in the big leagues in a couple of years – and he never did make it.

JH The highway to the big leagues is littered with a lot of bodies on the way.

LJ [laughs] Boy, you’re not kidding.

Lynn’s route to the 1975 Emeralds was affected by full rosters and player movement – and bonus money. It was common for minor-league players to receive bonus money when they advanced a level and stayed there for 90 days.

LJ In 1974, I was in Seattle; in 1975, I went to AA, but I went as a shortstop.

I had, that winter before, gone to Instructional League. The last three weeks, they realized that they were short an infielder up there in AA. And so they said, well, let’s see if Lynn can do that. So the last couple of weeks of Instructional League, I moved to shortstop. We had already had three outfielders that they really liked: Steve Henderson, Danny Norman, and Donny Lyle. And we had Rick Colzie.

So they knew that they were loaded in at the Tampa level. So they move me to shortstop. Shortstop was a disaster in AA. I was way over my head. So before I got my 90-day bonus, which I think was $1,000 or something like that, I was like, days before that, they sent me to Eugene. They couldn’t send me to Tampa, because that outfield was full. So they sent me back to Greg’s team.

The Tampa Tarpons were part of the Florida State League — considered to be more advanced than the Northwest League, of which the Eugene Emeralds were a member.

JH I did kind of wonder about that, because when you see A and AA in the same season, you think — and you’ve had a decent-enough 1974 season — you think, okay, did he start there? Did he finish there? Which way did that go?

At least it wasn’t one of those deals — I’ve heard of guys getting sent out at 89 days, just to keep from paying them the 90-day bonus, and that kind of stuff.

LJ Yeah!

JH Was it hard to be a guy who hit .440 in college, and then struggled in AA? Was that tough to deal with?

LJ No, not really.

JH I mean, that’s slow-pitch-softball kind of numbers.

LJ But you gotta remember too, we didn’t play that many games. You know, back then I think we had a 16-, 18-game schedule. And most of them were doubleheaders.

What made it a little bit easier for me was, I went away to a summer college league. And my brother preceded me going down to the Shenandoah Valley League. And so when I went down there, it was a little easier because I got a little bit of experience, but when I went down there, the manager wanted me to be a pitcher. But I didn’t want to pitch.

So during that whole summer, I pitched a little bit, but I only got 35 at-bats down there during that time. I think I hit .335 or something like that during those 35 at-bats, but that’s all I got. I started once we had we had Division I players on our team; they had to go back to school for orientation and whatever, and they had to leave early. So that left outfield positions open during the championship game.

And we had a reunion two years ago. I didn’t even know what I had done. I didn’t remember what I’d done, but the guys are telling me, Oh yeah, you made a couple of great catches. You went four-for-five in a couple of games, and we won the championship. I didn’t even remember what championship. But that was a long time ago.

Lynn was promoted to AA Three Rivers for 1975. But he was miscast as a shortstop — and he knew it.

JH So you started 1975 at Three Rivers as a shortstop, and then they sent you back to Eugene, and you were an outfielder there?

LJ Yes. Now I went back as an outfielder, and I had to — just at that point, you don’t really know where your career’s at. But I went back, and the good thing that I knew is, I was already familiar with Greg and had a decent year in Seattle with Greg. And it was — I was comfortable. Disappointed because I didn’t go to Tampa, but that was understood.

And here’s one of the things about going to Eugene: My career goes from Seattle — now I’m in the Northwest League in Eugene. Now, I remember from playing in Seattle, when I went to Eugene, I didn’t hit well in Eugene. And so I’m thinking, on the plane going there, what am I going to do? I’m going to Eugene. I know I don’t hit well in Eugene.

And there’s a reason why I didn’t hit well in Eugene: There’s a street light right behind the pitcher, beyond the fence —

JH Oh, no! [laughter]

LJ — that just, it gets in my head. And whenever a pitcher is out there and his release of the ball, it’s right out of that light. Now that light is a mile away, but so is my brain. It’s in my head. So I’m seeing the light, and not the ball. And so my first day there, I’m thinking, okay, I gotta get this done, or else I’m going to have a bad year.

So I have a bad first day. The second day, we go to batting practice and I’m thinking, okay, I’ve got the solution. There’s a batter’s eye out there, and that streetlight is between the batter’s eye and the fence. There’s probably a three-foot gap there.

So what I did was, I went and got a piece of plywood and I tacked the plywood up on the back of the batter’s eye, so that that streetlight was blocked out. The first night, when we played after I nailed that plywood up there, I missed it; I had it over too far.

So the next day, when I got to the ballpark, I got there early, took that piece of plywood down and moved it over, and I got the spot. The rest is history.

I went on and had a great year in Eugene, and it was because I got that street light out.

JH What jumps out at me, looking at that year, is 14 home runs. That’s way more than you hit in any other season. And 77 runs batted in, in A-ball. I mean, holy cow, that’s a lot of runs batted in.

LJ I didn’t do anything different than when I was in Seattle, though. My first couple of games, I think I hit two home runs in my first doubleheader, or something like that. But I was off to a good start. Then there was a couple of scouts: Rex and — what were their names? Two brothers?

JH The Bowens? Joe and Rex?

LJ Bowen! Well, one of them was telling me to move my hands and do this, you know, when he was watching me for batting practice. So what do I know? I’m moving my hands down to a lower position and all of a sudden I wasn’t hitting as well as I was supposed to.

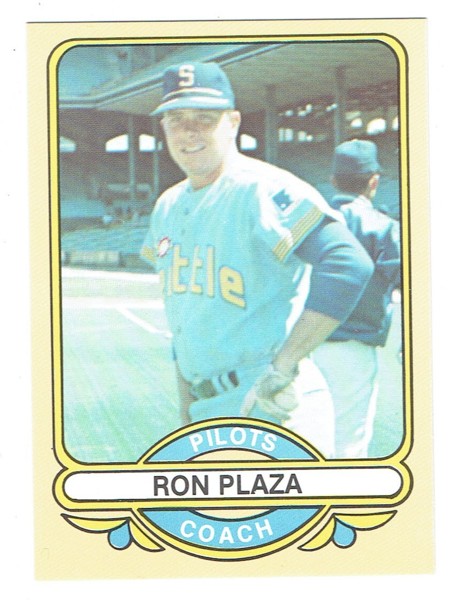

Well, Ron Plaza, he came in — and Ron didn’t forget anything. He knew players, and had a photographic memory. He knew exactly the way players were supposed to be. And as soon as he saw me, he said, What are you doing? You’ve changed. And I said, well, I changed because Rex told me to move my hands, and get them lower. And you know what he did? He turned right around and went right in to the clubhouse, and went to the office somewhere, and made a phone call back to the office. And he was hot. I had changed, and Ron knew that. When I went back to AA, I was just overmatched at that point. And the pitching was pretty good in AA.

When I came back to Eugene, let me tell you what, it was easy. Once I got that light fixed and the difference in the pitching was — just totally different.

Coming out early for extra work, as many Eugene players did, gave Lynn’s career a boost.

LJ And I found something out about myself, but it wasn’t without a lot of work from Greg. Because Greg, well, he used to — I don’t know how he did this:

Greg used to pitch – when we were at home, he used to throw 45 minutes of early work to us. And we had such a good team and a good relationship with everybody, everybody showed up early. So Greg would throw 45 minutes of early batting practice. And the whole key with Greg was to try to hit the ball off the L-screen and that was — we had to hit the ball off the — line drive off the L-screen, and he made a game of it.

And so everybody was willing to come out and work early, because we were having fun. And he was making us go up the middle, and keeping our weight distributed right in our approach up the middle. And we were doing it, having fun, not really understanding what he was supposed to be doing with this.

I mean, you could explain it, but when you’re young kids, you really don’t get it. And he made it fun. I mean, he made it fun. Then, you know what? An hour later, he’s back at it again, throwing batting practice. I don’t know how he did it.

JH He told me he used to have to have two sessions. There were something like 35 guys on the roster, and only 25 could be active for a given game. So he would get a bunch of early work done, and then the guys who were active for that day, he’d throw to them, and they would do all the stuff. Cause he didn’t have any help coachingwise, either.

LJ I think we may have had a pitching coach; I’m not sure. [Joe Verbanic] It was a relief when Scotty Breeden came in, because Scotty could take over throwing. And Scotty was like a machine, too; he could throw for hours on end.

But Greg was phenomenal — and he taught us to have fun. I mean, just flat out have fun playing the game. And when you did that, you learned how to play the game from each other, because you would talk baseball. You would sit around after the game and chit-chat and talk. I don’t know whether we were allowed beer in the clubhouse at that time. They don’t even have it at the major-league level now. But it used to be where we could sit around and talk, and that was a big thing.

the game. And when you did that, you learned how to play the game from each other, because you would talk baseball. You would sit around after the game and chit-chat and talk. I don’t know whether we were allowed beer in the clubhouse at that time. They don’t even have it at the major-league level now. But it used to be where we could sit around and talk, and that was a big thing.

JH Do you think that he was especially suited to work with young players? It seems that way.

LJ Oh yeah! No doubt. It helped that he was a schoolteacher. His communication skills were better than the average baseball coach. And I think he knew how to touch and reach back and touch people. And I’m sure some of us are oblivious to other people’s problems, but I think he could see that; he could understand things a little bit better than most, and he could put everything into perspective.

I thought he was — for me, I thought for the longest time, “why are you here?” Because he’s such a great communicator, and he was a great coach, and could teach. Why is he still here? Well, it’s because he was a schoolteacher, and he only had so many months [before he had to return to teaching school].

But still, as later days went on, obviously when he went to San Diego, at least he got a reward out of it.

JH He got a payoff for all those years in A-ball.

LJ Yes!

JH But is it possible, that he was better suited to work with younger players, moreso than the veterans who might not buy into this program?

LJ Well, I think that Cincinnati knew where he belonged, and he did belong there. He gave us a passion. He gave me a passion for the game that I still remember to this day. To me, I think I had really two really good managers that I really had a lot of respect for: Greg was one, and Dick Howser was the other.

JH How was Greg as a bench coach and running a game and that sort of thing? What’s your take on how he did there?

LJ Well, he never embarrassed anybody. I don’t remember him ever yelling at anybody. He communicated with people instead of — he didn’t force the issue; he sat down and explained issues. And that was what we needed at that time.

JH From what I understand, he had the opposite approach of a guy like Ron Plaza, who – it seems that opinions on Ron seem to be really polarized. The guys either loved him or just couldn’t stand him.

seems that opinions on Ron seem to be really polarized. The guys either loved him or just couldn’t stand him.

LJ [laughs] You got that right! I actually — you know what? With Ron, you were afraid of Ron, but you had great respect for him. And when Ron — you had to understand his looks, you had to listen to his words and you would understand where he was coming from; because Ron didn’t have to say much, because he was direct and to the point.

And Ron would — he always had his aviator glasses. But you could see him — when he started batting his eyes behind his aviators, you knew you were in trouble. He was gonna chew your ass out. And you’re going, oh, no! I said the wrong thing!

He’d ask you a question, and you’d think you’re smart enough to — and he knew the answer. He knew what the answer was going to be. And you’re trying to match wits with him. And as soon as you open your mouth, they’re going, ahhhh! And his eyes started batting, and it’s Oh, frick, that’s the wrong answer! I shouldn’t have said that!

And I learned that when we were in Instructional League, and he asked me a question, and I knew what the answer was. So I told him, this is what I did. It was something about going after a ball in the correct way. And I knew the answer, and I said, yeah, that’s the way I did it, and wrong answer. I didn’t do it that way. And I knew I didn’t do it that way. And he started batting his eyes and started chewing me out. And I said, I am never going to answer another question from him. I’m just going to sit there until he tells me what to do.

Plaza spent many seasons as a roving instructor for Cincinnati farm teams.

LJ Well, with Ron, every time he’d come into town, you’d look for Ron. You would, Ron, am I doing this right? Am I doing this? Cause you knew he knew what he was talking about, and this is the way it’s supposed to be done. If he told you, that’s the right way. That’s the Cincinnati Reds Way. And so as you got older, you wanted him around. You wanted his advice.

When I was in AAA and I was doing well, he came in and it was the last day — he was there for a week — and I said, Ron, what’s wrong? Are you mad at me? He said, no, why would I be mad at ya? I said, you haven’t talked me for a whole week. He said, you haven’t done anything wrong. Just keep doing what you’re doing. I’ll let you know when you do something wrong, and you just keep doing what you’re doing. And at that point I said, okay, I totally ‘got’ Ron at this point.

So when I made it to the major leagues, Ron was the first-base coach for the Oakland Athletics. I never wanted to see and get acknowledgement from anybody more than Ron Plaza. And he was happy to see me because, you know what? I was a guy that I think, with all the guys that were in my draft that was supposed to make it, I was a borderline guy. And he was genuinely happy to see me. And I was never so happy to see him and say, I made it. I’m here and I’m here partially because of you.

JH You must’ve felt a real feeling of vindication and satisfaction from that.

LJ Oh, absolutely! Absolutely. He was my guy that if he said you’re doing good at the major-league level, then I got the okay — the seal of approval.

JH And you mentioned The Cincinnati Way; the Reds were sort of well-known at that time for things like teaching the same relays and cutoffs and things all the way through the organization. So if a guy got moved up or down they would know how things were to be done.

LJ That was it! That was the whole premise of their organization was — I teach from the, if I sent a Rookie League guy to AAA, it’s the same thing; the process is the same. And you know what? To this day I teach — I volunteer down at my alma mater, Thiel College, and to this day, I teach the same exact thing.

JH Well, it seems to work!

LJ Yeah. The teaching techniques, for some reason — outfield play, throwing a baseball — have changed. And I don’t think guys’ arms are what they used to be, or whatever, but that whole — what process is better? Well, I’ll tell you what, there’s the old staple was the Cincinnati Reds’ fundamental way of playing baseball. It’s still the foundation of what I’ve taught.

JH I grew up on Reds baseball, and the reason that I just revere those 1960s-70s teams is how they played: so fundamentally sound and all that. And I was primarily an outfielder. And when I see outfield play today, I look at what in the world is going on? and where are the arms? Where are the fundamentals? Can anybody throw out anybody at the plate anymore? I mean, seriously!

LJ When you’re only 90 feet in the outfield grass, and you can’t throw a ball accurately to home, there’s something wrong. And it’s technique. It’s fundamentals. It’s mechanics. And we had — we were taught — all of those things. And it was simplicity.

If I was gonna do it, the AAA guy was gonna do it. If the rookie guy was going to do it, you knew, guess what? This — and we all knew that. Now it was a matter of, they’ve given you the tools; now you take it to the field and see if you can get it done, okay?

The 1975 Emeralds formed a special brotherhood that’s rare in professional sports.

JH You mentioned also on the 1975 team, how many of the players came out for early work. You guys seem to have this extraordinary bond, beyond just being a good team. How do you account for how that team came together, and the fact that they’re still having reunions, and everybody’s still in contact after all this time?

LJ Well, winning has a lot to do with it. That winning experience, I think makes it that much more memorable. And sharing that winning part of your life, that winning year. A lot of people don’t get an opportunity to experience that. That’s a big deal. For a lot of people it’s a – hey, I’ve gone on and got to the top, but yet I still remember vividly a lot of the things that happened at that level.

JH There’s quite a number of the players who say that was either their most-memorable year in baseball, or their favorite year in baseball, regardless of how far they got. Even the guys who made the big leagues still point back to 1975 and say you know, that was a real key time in my career.

LJ And I agree with that. For me it was a pivotal — it was a reload for me. Where you have doubt. You had success, and then you have doubt, because when I went to AA, I was overmatched, and you doubt yourself. That reconfirmed when I went back to Eugene, and putting the work in and being able to relax and enjoy baseball like I did before I even signed.

That was a total restart for me, and where I think my career started on the upswing. Even though I had to go back through AA again, I knew I could do it. It was a matter of getting my head around it all.

Lynn’s Eugene teammate John Harrison: LOVE Lynn! An incredible athlete! He was Seattle’s best player in 1974. He just stood out. With Eugene, he was our Roberto Clemente. Love him like a brother!

JH It sounds like you got your bearings and got your feet under you, so to speak, and then you realized you had the ability to do it; it was a matter, then, of applying it and going forward?

LJ Yeah. Because I thought I was given the right tools. And sometimes you don’t realize what you’ve been given, until you have to struggle a little bit and you go, well, where am I going from here? Let’s start with the basics. Okay, this is what I need to get done. Know there’s a means to an end.

And so once you realize that, and realize where you’re at in the whole system — it’s a sense of reality on where you fit in the grand scheme of everything. And that kinda gives you a starting point on what you have to do to get to the next point; get to the next level.

Where’s your success coming from? Well, you hope that what you get from the organization is what you need. And I think, Cincinnati gave it to you; now it’s a matter of you getting the opportunity. And once you get the opportunity, can you kick the door open?

I think I did that twice when I was with Cincinnati. I did it in Eugene, and then I did it the next time in AAA; especially in AAA because AAA for me, I was going to — that was going to be my last year. That was my “major leagues.” I had already figured out that I was looking for jobs, and I had a family friend who was in the Boys’ Club, and I was looking at all the different cities, hoping that I could get a job in the Boys’ Club.

So toward the end of the season, when I was starting out in AAA, I thought, well, let me fly. If I can fly to those different cities, that’s my major leagues. And I get to fly to play baseball. And lo and behold, with Ray Knight getting hurt, the rest is history. And that’s luck. That’s being in the right place, the right time, and being able to get your foot in the door; kick it open and don’t let them shut the door.

JH But you were prepared for that to happen as well, though. I mean, you got to AA, and that was kind of a wakeup call. But when that happened at AAA, you had to have been ready for that, or you wouldn’t have produced at that level.

LJ Exactly. And you know what? It’s a matter of being able to focus. And that year I found my focus. When I was in AAA, I was trying to find a way of focusing and staying focused. My brother Darryl was two years ahead of me, and he was playing in the Yankees organization. He’d signed two years before. And so he was my sounding board whenever I needed to talk to somebody, because he was a really good hitter. And of course, everybody wants to hit. So he’s my sounding board on everything.

So what I did was, I found a Thunderbird hook rug. And it had short pieces of yarn, and you hook the yarn into this plastic grid. It’s color-coordinated and you hook them and you end up with a Thunderbird shag-carpet rug, sort of. And it’s only like two feet by three feet. Every night, I would hook this rug for a half-hour, you know, 10 minutes, whatever. I would hook it. And it takes a while to hook this rug, now. All season long.

I’m focused in; I’m playing great. I hook my rug, I lock in, I think about baseball before I go to bed, wake up, do the same thing. Over and over and over. Never did finish it, though, and I didn’t know what happened to it. I came home and then I went to the Dominican Republic, winter ball. The rug got put away, and I never saw it until this year. I was uncovering some boxes and lo and behold, I found that rug. And I gave it to my middle daughter. I gave it to her, and I told her the story about that rug. So I said, this rug is for you to finish.

JH You have an heirloom now.

LJ Yeah, exactly.

And more about Greg Riddoch and his influence:

LJ I keep wanting to go back to Greg!

We were such a good team in 1975. And during that time, I think we hit .300 as a team. And every time we had clear skies, the Moon would come up over the over the left-field fence — big, big Moon come up over the mountain.

And whenever that Moon got up over the mountain, we kicked ass. We would just — that team had no chance. And it got to the point where, when that big Moon would come up over that — start rising — you could hear the fans go, here comes the Moon! Here comes the Moon! And sure enough, we’d just start wailing away, and whacking away.

So we’re playing the Dodgers, and the Dodgers were a real young team. They lost 25 games in a row at one point. They were reaching a record, or whatever. And I don’t know whether they had stopped the streak or not, [they had not] but it was during the first or second inning when they hit, they scored like eight or nine runs, and we were booting the ball; we looked like The Bad News Bears out there.

We were kicking everybody’s butt, and here’s this young team and they were just beating our brains in. And we came off of the field, and the fans are booing us. We’re looking that bad. We’re expecting Greg to yell at us, because we were that bad. And our heads are down; we’re kind of ashamed. And Greg’s not where he usually is. He’s not in the right corner of the bench, waiting for us to get in, and for him to say something.

So we get in, and you look down at the other end of the dugout, and Greg is down there and he has a sanitary sock wrapped around his neck, and he’s hanging from a hook.

And it was — we just looked down there and we saw him and he goes, you guys stink! And he’s hanging there with his tongue out, and we’re laughing now, because it’s funny.

We went out that same inning and scored 10 runs, and the game was over. It was over. Talk about turning it around in an instant, with a joke! And that is probably my most memorable thing that I can remember from Greg that hit home: Relax. You got this. Get back to doing what you’re doing. And that’s exactly what we did that inning. And we turned the whole game around, and he did it with just — down at the end of the dugout with a sock around his neck.

JH Well, that’s one way of making a point. I mean, after it gets to a certain point, yelling isn’t gonna do any good anyway.

LJ No, he knew we were just — it was just of those odd games, you know, where we just stunk. And at that time, the Dodgers, of course, this was their rookie A-ball team from Bellingham, and they had 16-year-olds. They’re 16, 17, 18 years old, and they weren’t supposed to be beating us. And they didn’t.

Not that night, they didn’t. But after losing the first 25 games of the season, Bellingham did win its first game – beating Eugene 5-1 on July 12. They finished 17-61.

JH A funny thing here: part of my research for this book was digging up as many game stories and box scores as I could from that 1975 season. And I think I just found the one you’re talking about. It says, “down by nine, Ems win by five.”

LJ [laughs] There it is! That’s it!

JH Down by nine runs, and then had an 11-run inning of your own. But wait a minute, it says here, though: The bottom of the sixth thing, Tommy Watkins popped out to center field, but then Lynn Jones walked. Obviously you keyed the rally!

JH Lynn Jones walked, as did John Harrison. Marlon Styles lined a single to right-center, Mickey Duval pinch hit a single; Harrison advanced the third on the relay. Styles went to third on an error, scored on a wild pitch. George McPherson walked. Bill Bird forced him out. Barry Moss tripled. All of a sudden it’s 9-5, and it goes on and on and on. I mean, it’s unbelievable.

LJ You know, that might’ve been one of my most memorable innings and games. And you know, the way it came about — and of course, that’s the rest of the story on how that inning started. It started before the inning got started, before the first pitch of that inning. And Greg started it.

JH That’s August 6, 1975.

LJ Well, hey, I’m not lying. [laughs]

JH There you go!

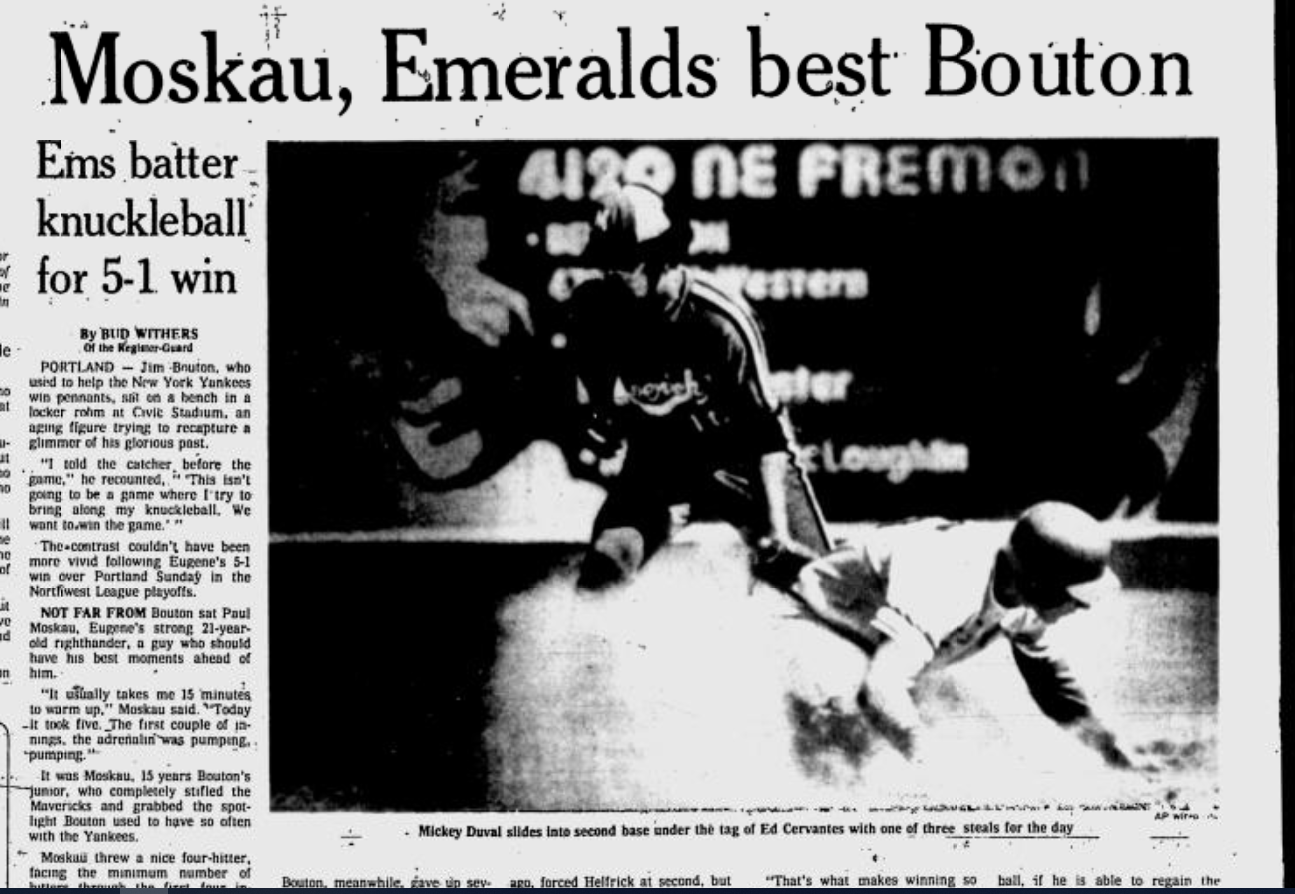

During the first game of the 1975 Northwest League playoffs against Portland and ex-Yankee Jim Bouton, Lynn had a tape-measure home run that all of the Eugene players still talk about.

LJ And you know, I hit a home run off of Jim Bouton during the playoff. And I don’t know how,  whether I broke that bat later in the game, but anyways, I still have that bat. John Harrison had that bat for probably 15, 20 years, and he sent it to me and he said, hey, I want you to have this. This is the bat you hit the home run off Jim Bouton. And I still got it.

whether I broke that bat later in the game, but anyways, I still have that bat. John Harrison had that bat for probably 15, 20 years, and he sent it to me and he said, hey, I want you to have this. This is the bat you hit the home run off Jim Bouton. And I still got it.

JH Nice! What was your thoughts on playing Portland in those days? I’ve seen that documentary on them [The Battered Bastards of Baseball] and I know Greg was not too enamored with the Mavs.

LJ No! We hated playing them because they were cocky, they were brash, and they were all older players. My goodness. They had Reggie Thomas.

JH He was the star of the team, supposedly.

LJ Well, he was a centerfielder. He had AAA experience, and he could steal bases, he could do a lot of things. But our pitching was a whole lot better than his hitting. And they had T-Bone Jones — I think the Phillies picked him up the following year, because I played against him.

And no, I did not like playing there because it was more — it was like playing probably in like the Dodgers when they’d played in the LA Coliseum. You know, it was a football field, and so it was not shaped in the right shape, but it had the Jantzen Swimwear lady [signage] out there.

They were in the other division. So we knew for quite a while that we were going to play them in the championship. And of course, we were pretty confident and they never, during the season — if we had played them, I don’t think Jim Bouton, they didn’t want him to pitch against us. They wanted to wait until we had met them for the championship.

And he had no chance.

JH Did you hit a knuckleball off him for the home run?

LJ I don’t even remember. All I know is, we beat him up good. We were young kids. We didn’t know any better. We didn’t treat him with any respect, that was for sure.

But we didn’t like their owner, Bing Russell. Of course, everything was about the Mavericks and Bing and the whole bit. And they kind of dismissed us as being younger kids, and they were going to kick our butts. And that wasn’t the case.

JH They never did win a championship, all the years they were there.

LJ And when we were up in Boston [as a base coach for the Red Sox], I was close friends with Ron Jackson. And Papa Jack, he knew Kurt Russell when he was with the California Angels. He had run into him and he’d come in the clubhouse, and so he knew him, so Papa Jack invited him back to our coaches’ room. So we talked about Portland—the Mavs — because he had played a couple of years with them.

JH When I look at your career and I think of how things were back then, wasn’t there a lot of thought that a typical progression would be two seasons at each level?

LJ Well, yeah, that’s pretty typical, but it really all depended on how stacked your organization was. And of course, we only had to go by what we were in. I mean, our organization was stacked, and especially the AAA level. So there was space for us at the AA level, and it’s like when we were – when, that following year, after 1975, I went back to AA as an outfielder.

And so we had Steve Henderson, Danny Norman, and myself and Rick Colzie, until he got sent out. He got sent out and I can’t remember who else, but anyway, we were there — I knew I was there [in AA] for at least two years, but Danny Norman and Steve Henderson, they were higher up the list as far as prospects go. They were big; they were faster. They were potential home-run hitters. And I understood that. So getting the opportunity to play was gonna take me two years in AA.

And I’ll tell you what: AA was hard. I thought the pitching was very, very good. And I didn’t think I was going to ever get out of AA.

JH As I remember in those days, the Eastern League had a reputation as being real tough on hitters, and that the breaking ball was a lot better there, but it was a real –

LJ Oh, the sliders were nasty there. I mean, it was so hard. The pitching was just — the pitching was better in AA than it was in AAA. They threw hard, and the fields weren’t lit up like AAA. And they had good sliders.

JH The thing about the AA slider is — something that I’ve heard about the Eastern League in those days, quite a number of times — they said, boy, that was the real pivoting point. If you could get past the Eastern League, then you — and I’ve heard a lot of horror stories about playing in Three Rivers — if you could get past there, if you could survive Three Rivers, you could go all the way.

LJ Yup. Yup. I truly believe that.

What we used to do, we’d look in The Sporting News. They used to give an account of the hitters — hitting statistics of all the players. And once you got to AA or AAA, they pretty much named the top 100 hitters, or whatever it was. Over in the Pacific Coast League, everybody’s hitting .343. And it’s like, well, wait a minute. Are these guys that much better? Why are they hitting better?

Our lead guy — our number-one hitter in the whole Eastern League — may have been at .310.

JH Yeah. You didn’t have Albuquerque to hit in, either!

LJ Oh, no, no. And that’s where the Dodgers were.

JH The Dukes!

But you did manage to survive AA. I mean, it took a while, and really, when you talk about Henderson and Norman, I guess the Seaver trade sort of gave them a better chance, and unlocked the pipeline for some of the rest of you guys, didn’t it?

LJ Absolutely. It did. No doubt. I mean, it threw space above me. Now they went, I think that first year they were in, which probably would have been 1976, 1977, I can’t remember. It must have been 1977.

JH Yeah, the Seaver trade was June, 1977.

LJ They got traded in 1977 and with Pat Zachry, Santo Alcala, and —

JH Alcala went to the Expos; Doug Flynn went to the Mets.

LJ Doug Flynn, yes.

JH Yeah, The Glue, as he refers to himself. But no, it was Henderson and Norman and Zachry and Flynn, I think was who it was.

LJ What they ended up having to do was they had to fill some spots up, and of course, we had Champ Summers, who they sent down. And we didn’t know, nobody knew, how old Champ Summers was.

JH [laughs]

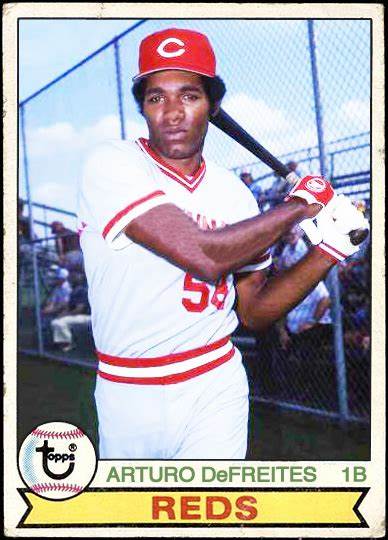

LJ Back then, I don’t think they really cared about what the birth certificate said, as long as you could hit. And when they sent Champ down, there just — maybe he wasn’t playing well up there and maybe defensively, he wasn’t the guy they were looking for. So when they sent him down to us, down in AAA, my goodness, what a phenomenal year he had. I mean, there was no stopping him. And then Arturo DeFreites, I think he hit .328 and had 28 home runs or something like that. He had a bunch of home runs, but we had — that team was loaded, loaded.

JH What happened with DeFreites? He never really seemed to make it.

LJ No, he didn’t. And then, I think I ran into him. He was scouting, I think he scouted for a long time. But he did not make it. I don’t think he went back to the majors after he went up after us in 1979, I don’t think, unless he was back and forth a few times.

JH He just never either got a full shot or merited a full shot, whatever you want to say. But he was kind of on the Indianapolis shuttle.

LJ Right.

JH And never really — one of those guys you think, geez, what would he do if he got 250 at-bats? But there was never a chance to find out.

LJ You know what? It’s the luck of the draw sometimes. You never know if you’re going to get that shot. And for a lot of people, that’s just the way it is. I’m sure there’s a lot of guys that are like that.

Lynn had more thoughts about his manager at Eugene:

LJ Getting back to Greg: Greg was one of those — as far as getting — understanding players: with Greg, he understood. We always had fun, with guys telling jokes. Guys goofing off. He would let you go. There was discipline there, but when it came to having fun, he would let guys have their fun. And I think it was Robbie Williams, he was a pitcher. And he was a relief pitcher. And Robbie got caught out, and he was married, and he got caught out after curfew. And back then it was matter of going to a bar and, he missed curfew and it was $25.

And Greg knew he couldn’t pay — he couldn’t pay $25. His whole paycheck went home, and we weren’t making that much money to begin with, where I think we were only making maybe, let’s see, $500, I think. So he may have been making — it was his first year, so he may have been making $500 a month. And so his paycheck’s going to his family or his wife, and she knows where every penny is at, so he couldn’t pay.

So we go into Portland and we go for early batting practice. So we’re sitting on the AstroTurf there early. We get out there early, because Robbie has to pay his fine. So we have a bunch of guys out there. Robbie has to — his fine is, he has to entertain us for an hour. That’s his fine. And you know what, he told jokes for a whole hour, and he had us in stitches. It was hilarious. It was the funniest thing.

What a great — to me, that was understanding of how you get around things and you build good rapport with your players, with your coaching staff. And instead of paying the money, he had to pay in jokes. And he delivered, too. He absolutely delivered.

JH Wow! Did you or do you still take some of the things you learned from Greg into your own coaching, whether it’s major-league or college level, in your own coaching career?

LJ Yeah, yeah. Have a basic understanding of where the person is from. What his background is as far as baseball experience; his understanding of the game, how it needs to be explained. Listening is one of the big things. Don’t just command what you’re teaching, but make it understandable; make it comprehensible to the individual. And I thought Greg was phenomenal with that. And he could do it in a fun way and you end up, you found out that you did a lot of work and made a lot of progress, and yet still had fun doing it. It was never a chore.

It was never a chore with Greg to work, and put the extra work in.

In 1978, Lynn was at AAA Indianapolis. He hit .328 with 62 RBI in 126 games, but was not called up by Cincinnati – even when the rosters expanded in September.

JH You’re still working your way up in 1978. You hit .328 in a full season of AAA, and don’t even get called up at the end of the year?

Now, listen: I remember the 1978 Reds, and they were no great shakes. I can’t see how a guy who .328 in AAA, he doesn’t get a callup. What is up with that?

LJ Well, here was the thing: Since I wasn’t on the 40-man roster, they weren’t going to make a spot for me. At the time, we had — oh my goodness, let’s see: Harry Spilman, Ron Oester, Mike Grace, Champ Summers, maybe Arturo DeFreites went up then. Maybe Dan Dumoulin. And I think Angel Torres may have gone up.

spot for me. At the time, we had — oh my goodness, let’s see: Harry Spilman, Ron Oester, Mike Grace, Champ Summers, maybe Arturo DeFreites went up then. Maybe Dan Dumoulin. And I think Angel Torres may have gone up.

For one, we were in the midst of a playoff with Omaha, which was Kansas City. And they had told everybody before we started the playoff, who was going up. Well, now, think about back then, when guys weren’t making a whole lot of money; you think you really wanted to play the AAA playoff, when you could be making major-league money, even for those 30 days or whatever they wanted?

There were guys that wanted to get there — even if they were going to sit the bench. Cause we had some guys, like Champ Summers, who had been there [in the big leagues]. He wanted to get back in a hurry. He couldn’t care less about the playoff. And he had a great year. I think he hit .376 [.368, 34 HR, 124 RBI].

We had a phenomenal team. But you know, that was one of the reasons why I didn’t get called up. During that time, they had already had — they were gonna add right there alone, maybe seven or eight guys to the roster. And back then, I don’t think you did that a whole lot — add that many guys.

JH Yeah, they didn’t. I mean, it’s surprising to me: You were not on the 40-man then, so they would’ve had to clear a spot for you on the 40-man to call you up?

LJ Yeah, probably. And then when it came time to protect me, we had three guys that were younger guys: Eddie Milner, Paul Householder, and a couple other guys, and they protected them. I happened to be down in the Dominican Republic then, when I found out that they didn’t put me on the roster, and that made me eligible to be drafted. Of course, I didn’t know that at the time.

But I actually called up [Reds farm-system director] Chief Bender, and he accepted a collect call from me from the Dominican Republic. And that is extremely rare, because if you knew Chief Bender, we had to fight for every nickel and dime from him.

And as soon as he got on the phone, he goes, well, you know, Lynn, I generally don’t accept collect calls, but since it’s you, I guess I’ll talk to you. And he allowed me to air my grievances, and then that was it. And at that point I ended up being drafted by the Tigers, and the rest is history.

When I was in AAA, I went there just to play defense. I think I had just received the Silver Glove, minor-league Silver Glove, which they don’t give out anymore, from Rawlings. I’m leaving AA and Roy Majtyka, who was my manager in AA the year before, said, I’m going to take you with me. And hey, it didn’t matter to me. I had a great spring. And I go and I make the team. He told me he took me there because I could play defense. We had Ed Armbrister, Champ Summers, John Valle, and Arturo deFreites, and they weren’t great outfielders. So I knew I was going to get a chance to play, at least during the last part of the game.

I had signed a contract with the Reds, and I made a deal with Chief Bender: if I made the AAA team and I was doing well, he’d give me a $100-a-month raise, retroactive. Now, we’re talking about a $100 raise. And so he agreed to it. So a month after the season starts, Ray Knight gets hurt.

So Ray Knight gets hurt at the big-league level. They wanted to take [Mike] Grace, who was our third-baseman, and take him to the big leagues. He was our number-two pick in my draft year, and was on the 40-man roster. They wanted to get him to the big leagues. He’s going to go there, and he’s going to sit the bench. So he leaves. All along, I think what they really wanted to do was take Harry Spilman and move Harry to third base.

So while Grace is gone, they move Harry to third base, bring Arturo DeFreites in to play first base. They move Ed Armbrister to left field, put me in center field. The rest is history. By the time Grace gets back in four weeks, six weeks, or whatever it was, they can’t get me out of the lineup. I’m as hot as you could be in the leadoff spot. And I’m starting the rest of the year.

And when Chief Bender came after that month-and-a-half, and I was already off to a good start, he came in and I’m expecting to talk to him about that $100 retroactive raise. And he came and went and hadn’t talked to me. I called him up again and said, Hey, Chief, do you remember our deal? And he goes, no, I don’t remember that deal.

JH Oh!

LJ And I said, Oh, we had a deal. We had a deal for a $100 raise, retroactive. And so I explained it all to him. He goes, well, if you explained it like that, I guess I made a deal with you. So he gave it to me. But that’s how hard we had to work for a raise.

JH That was a convenient lapse of memory, wasn’t it?

LJ Oh, yeah! But you know what? I loved Chief Bender. You knew what to expect out of him.

And there’s other stories where we’d send contracts back and the whole bit, and, you know, he just was tight with the money.

JH I guess a lot of guys in those days had clauses in there where if you moved up a level and stayed X number of days, you got a bump up — 100 bucks a month, or whatever.

LJ Oh yeah. It was a bonus clause. And every level you’d go up, and you had to stay for 90 days. If you didn’t stay for 90 days, then it goes back. And that’s what happened to me.

And when we were coming up, in every level, you didn’t move up unless your offensive numbers – if you didn’t hit .300, most of the time you weren’t moving. And especially if that guy in front of you was hitting .300 at the next level, you aren’t moving; or hit home runs or whatever, you weren’t moving. You had to outshine that guy ahead of you in that position, or else you weren’t moving; you’re going to stay [at the same level].

And we looked at that through the whole system. Because back then, I mean, that was when Youngblood, Griffey, Tommy Spencer, those three guys were in AAA, and they weren’t moving. And when you’re in AA or you’re in a high-A or whatever, and you’re looking at it and going, these guys are hitting .300, and they’re not making the big-league team. Where are we going?

JH A guy can hit .328 and not move, if you know what I mean!

LJ Yeah, yeah.

JH Hit .328 and not even be on the 40-man! You hit .328 now, they couldn’t get you up to the big leagues fast enough.

LJ You couldn’t get there fast enough. Exactly. Yep.

After five years in the Cincinnati organization, Lynn was selected by the Tigers in the Rule 5 draft, which is designed to give players a chance to avoid being “stuck” in the minors without a legitimate chance to play in the big leagues.

LJ And you know, the one who gave me my job, really, was Les Moss. And I had played against Les Moss when I was in AAA with Indianapolis and Les was the manager for Evansville. And I just had a phenomenal year against Evansville. And I guess when it came right down to the draft — the major-league draft — Les and the scouting department were instrumental in getting me [to Detroit].

A quick story on how well I was doing against Evansville:

I remember having a conversation with Bruce Kimm — Mark Fidrych’s kind of “personal catcher.” But he was in spring training during that time. And he asked me, do you remember when I called time out, and I had to go into the clubhouse and fix my shin guard? And I said, yeah, I remember that. And I did. And he goes, well, I called time out, said my shin guard was busted. I had to go change it. So he ran through the dugout, up into the clubhouse, and he came back like a minute later or whatever.

And he said, do you know why I went up there?

No, I don’t.

I went up there because you were hitting us so well, I forgot what we were throwing you, and how we could get you out. So I had to go upstairs and look in the book to see what we were throwing you.

Then he came back and I thought, now there’s a compliment, right there!

JH That’s pretty clever. But if they’re having that much trouble getting you out and they’ve tried everything else, better go back to basics and see what you can do.

LJ I always did well against them, and they had guys that could throw really great changeups and good sliders. And they had a guy, a pitching coach [John] Grodzicki, and Grod was phenomenal teaching pitchers how to throw a changeup — but it didn’t matter to me. That was just one of those teams I got.

When Detroit drafted me and I went to spring training for the first time in 1979 with Les as the manager, from day one when I went into spring-training camp, Les Moss pulled me aside and he said, I don’t want you to worry about a thing. You are going to be my fourth outfielder. That’s a pretty good vote of confidence coming from your manager.

JH For a rookie!

LJ And never having been at a spring training, major-league camp, that was a shot of confidence that I needed, and I had a good spring. So Les was my guy.

JH So you’re Detroit’s Rookie of the Year in 1979, but I see here you spent part of the 1980 season in AAA: 34 games. What happened there?

LJ I had a knee injury.

JH OK, because there’s only 30 games at the big-league level, and 34 in AAA. So were you try to rehab from that?

LJ Yes, yes. I had a swelling in my knee and I had articular cartilage damage in that next spring. And when I went there, my knee kept swelling up and I’d get it drained. And finally I went up to Lansing. When the season started, I may have started a few games. And then I can’t remember whether I played first and then went to the disabled list or whatever.

But I ended up, I think Lanny Johnson was the surgeon, and he was one of the first guys to do arthroscopic surgery on athletes. And he repaired my knee without doing the big slice and the zipper and the whole bit. And then I took I think nine weeks of rehab. And when I came back, I think I went to AAA then, and rehabbed, and then came back and played. I can’t remember the sequence — whether I had played, I think I had played a few games to start the season.

When I went to AAA, I knew I was going to get called back up in September, but my roommate was Mark Fidrych.

JH Oh, man! [laughs]

LJ Yeah. When I came back, he goes, hey, why don’t you just room with me, so you don’t have to get an apartment? Oh yeah. He took me in.

JH How was that experience? [laughs]

LJ He was a good, down-to-earth guy. High energy. Loved him. Just such a sincere individual; fun-loving and yet tragic because he was basically doing total rehab during that time. And it was sad that he couldn’t be his old self.

JH I always got the impression that the Tigers brought him back too soon.

LJ Oh, they did. They probably did. Cause I know that I saw, I have it on my recorder. ESPN did a story on him, and that was one of the hypotheses or rumors that they brought him back too soon. And I forget who said — one of the players or Freehan, maybe Rusty Staub — and Rusty said that he thought they brought him back too soon. Should’ve just given him a year off.

JH Somebody said at the time, one of the doctors said that you won’t really know if his surgery was fully successful right away; it’s gonna take him pitching a while to see if he does anything to his motion or anything happens. And sure enough, he came back and [got] a torn rotator cuff, and they couldn’t figure it out.

And I don’t like the idea that people dismiss him as a one-year wonder. He’s a fluke. No, he got hurt. If he hadn’t been hurt – I realize you could say that about a lot of guys. Hey, I’ve torn both rotator cuffs, so I know a little bit about that, but don’t act like he was some freak show; that guy could pitch!

LJ I’m telling you what, he was phenomenal. And he could throw 91, 92, 93 on the knees, with movement. And a phenomenal slider. He was he was the real deal, and he wasn’t — I don’t think he was a fly-by-night. He got hurt. And what a shame, because he was the salt of the earth. He was.

JH Now, what I remember about you as a player is: number 35, fast little guy, outfielder. Big glasses. Big mustache. Didn’t get to play a whole lot, for reasons that escaped me. Got a couple of World Series rings; one as a player and one as a coach. Is that a fair statement for how your career went?

LJ Yup.

JH Taking my memories and your stats and looking at them, you think, why didn’t this guy get a better chance?

LJ Well, I could tell you why! [laughs]

JH Please do!

LJ Well, Sparky Anderson was the reason why.

Sparky Anderson managed the Reds when Lynn was drafted by Cincinnati in 1974; he later managed the Tigers when Lynn played there, after Les Moss was fired in June 1979.

But it’s not that I have anything against Sparky Anderson. You’d have thought, since I came from  the organization that he led, I would’ve gotten more of an opportunity. But Sparky — hey, I was around for five years, and I was around longer than a lot of players that may have been, in some cases, better than me; but they didn’t fall into Sparky’s ideas of what he wanted out of his team.

the organization that he led, I would’ve gotten more of an opportunity. But Sparky — hey, I was around for five years, and I was around longer than a lot of players that may have been, in some cases, better than me; but they didn’t fall into Sparky’s ideas of what he wanted out of his team.

I know that I was well-liked over there, but I also felt that — and looking from Sparky’s vantage point — that I fit more into the extra-player mold and not the everyday player. And that was his thought. He was the manager, and when it’s his way or the highway, you go with his way. Because I saw a lot of people hit the highway!

JH Your stats sure show, and my memory is, of like a fourth or fifth outfielder. Because you played all the spots. I mean, it wasn’t like you were locked in as, okay, you’re the second right-fielder or whatever.

LJ I’ll tell you what: you know that old line, baseball been berry, berry good to me? Well, it has. It has been very good to me. It has been a struggle at times, but you know what? I’ve had a very good life with baseball. It’s provided me and my family a living all these years.

And I was able to be in the major leagues. I was able to play there, coach there, got interviews for major-league manager jobs. And I can’t say enough — and yet I still like going back to the minor leagues. I had opportunities to go back and coach at the major-league level, but that’s not — that wasn’t my gig. I had teaching more on my mind, and giving back what I knew about the game and how to teach it.

And it all stems back from Cincinnati. It all goes back to Cincinnati.

Lynn Jones is a volunteer coach at his alma mater, Thiel College.