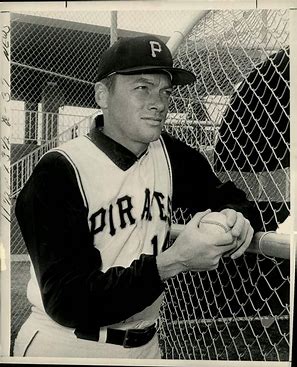

Larry Dierker was a fabulous pitcher for Houston from 1964-1976. He also had a long, successful run as a broadcaster for the team — and to the surprise of the baseball world, he went from the broadcast booth to the dugout as the Astros’ manager. In five years, his teams won four division titles — the most sustained success the Houston franchise had to that point.

You have an entire chapter in your book This Ain’t Brain Surgery about  Opening Day – from Little League forward. Why was that day so special for you?

Opening Day – from Little League forward. Why was that day so special for you?

In Little League, it was something. In high school, it was something. You had waited during the offseason for the chance to start playing again. There was a different emotion and feeling prior to the game and before the first pitch.

After that, you don’t have any sense of something beginning. It’s a process. Even as a broadcaster, Opening Day was special.

Your first Opening Day start in the big leagues was in 1968 against Hall-of- Famer Jim Bunning. And you told him ‘good luck, after tomorrow.’ How did he react to that?

Famer Jim Bunning. And you told him ‘good luck, after tomorrow.’ How did he react to that?

I think he understood. He was a veteran guy and I was just a young kid.

PITCHING

You signed right out of high school, and you were in the majors at age 17 in 1964. That’s rare.

The most difficult thing for coaches, managers, and general-managers is to project a pitcher’s career before he’s 24-25 years old. A lot of guys develop things maybe halfway through their career; others get a sore arm and never get it back.

GMs have a philosophy that you can trade for hitters and get free-agent hitters, but it’s better to develop your own pitchers, because of their variability from year to year.

In the 1960s, I don’t think college programs were as good as they are now. I think baseball people probably trust the colleges to do the same thing they would have, instead of spending money bringing a guy through the minor leagues.

You were largely self-taught as a pitcher.

I don’t remember anyone showing me how to throw a curve ball or a changeup. I didn’t even have them all the way through high school – just a fastball and a curve ball. I think maybe I just had a sense of how it should spin – seeing someone else throw one and seeing how it spun. I might have learned it from throwing baseball cards.

Is it true that you need three pitches to succeed as a starter in the big leagues?

Yes. Exceptions are someone who has a cutter. Guys who have that, since it’s their natural fastball, they can throw it to both sides of the plate and when you can do that, you can maybe add a changeup, maybe a breaking ball.

But most of the time, you need three pitches. With enough movement on the fastball, he doesn’t really need very much else. Jerry Reuss and Dave Dravecky come to mind.

Was your slider self-taught, too?

Real early on – within the first week or ten days of rookie league in Cocoa. They asked, ‘do you throw a slider?’ I said, ‘No, I heard of it, but I don’t know how to throw it.’ ‘It’s easy, throw it like a spiral in football.’ So I did that, and within ten minutes I had a slider. It was easy. How did I not know about that? Why didn’t I think of trying that?

For me, it was just thinking about how the ball should spin, and trying to make it spin that way. I learned everything but a knuckleball that way. I never even came close with the knuckleball.

I did have a screwball at the end of my career. It worked OK against a few left-handed pull-hitters.

A lot of times, it’s just experimenting with different grips. Other times, pitching coaches will suggest a certain grip.

I wish I would have known how to throw a circle change. My modified slip-pitch wasn’t all that much. Once in a while it would really help me, but most of the time I didn’t throw it often. Had I known the circle change, I probably would have had a better changeup. Mostly a “show” pitch.

How valuable is it to have a game plan for facing a given lineup?

I think there’s a number of starting pitchers who go out to the mound in the first inning with a plan for each hitter. More than half. I wanted to see how I feel in the bullpen, and then see if your sinker is sinking – get a feel for what you’ve got and emphasize the pitches that seem to be the best for you on that day.

Tom Seaver said that with good control, you can pitch hard in and soft away; throw hard when you are ahead in the count and slow when you’re behind. You could pitch everyone that way if you have command.

And if you have a complicated plan, you might clutter your mind instead of having a natural feel for what you have and what you want to do.

I probably would not have responded well if I had to take a sign from a catcher that told me I had to step off or throw to first, if I was in the mode that I wanted to make my next pitch.

Sometimes I just wanted to pitch. — Larry Dierker

The Dodgers were a difficult team for you to face — particularly at home. Can you put your finger on why they gave you so much trouble?

They always had good starting pitchers, and it was a good pitcher’s park in terms of the ball staying in the park. Usually I just got outpitched.

How much of an effect did injuries have on your career?

Everybody, sooner or later, will play with pain – chronic pain.

The first time I felt pain was in 1971, in my elbow. I was shut down in August and September. My elbow didn’t feel normal until Christmas. The next year, I was fine until I started having shoulder pain, and that became chronic.

Sometimes I maybe took a painkiller before the game. But I had a lot of games with no pain.

The last couple of years, the shoulder was like a pin cushion: cortisone shot after cortisone shot. Painkillers every single start. Hot stuff.

I don’t think I should have been pitching when my arm was that sore, but there was a sort of unwritten rule or ethic that if you could make your start, you made it. I was disabled a couple of times, but mostly found a way to manage it.

And how did you ‘manage it’?

I changed my arm slot over time. I started out throwing directly overhand, and at the end it was almost sidearm. You just try to find a slot where you can throw and it doesn’t hurt.

If you get a sharp pain, it’s usually when you make a transition – the first action of going forward – you get a sharp pain. You lose command. If you can find a slot where it doesn’t hurt, you have a lot better chance to make good pitches.

90 percent of players get released — they don’t retire. They get every dollar out of baseball. Usually they are released because of injury – an injury that prevents them from being a major-leaguer.

I don’t think they are necessarily doing young pitchers, or a team, a favor by protecting them. Most of the best pitchers when I played didn’t get up to the big leagues at 18, like I did – maybe age 20 or 21. They all came up in their early 20s, and most were not finished at 31 like I was. They were pitching 250 innings a year like I was, but they pitched longer.

It’s not a one-size-fits-all; some arms can take more throwing than others. I’m pretty sure there’s no way for doctors to test or guess by the way a guy’s arm is built how much of a load it can take.

Guys in my generation would have been really [irritated] to be taken out of a game after six or seven innings and 100 pitches — Larry Dierker

Guys in my generation would have been really [irritated] to be taken out of a game after six or seven innings and 100 pitches, if it was still tied or they didn’t trust the bullpen. Now they don’t even think twice; back then they wouldn’t have accepted that so easily.

After a couple of early near-misses, you threw a no-hitter near the end of your career, in 1976. I remember it because of your emotional reaction after the last out.

It meant more to me, because I didn’t think — it never occurred to me that I would pitch a no-hitter at that juncture, because of the shape my arm was in. (See the full story of the no-hitter here.)

I really felt blessed to have that happen, because after coming close a couple of times, then being all worn-out when it happened, it was like a gift from God, the way I saw it.

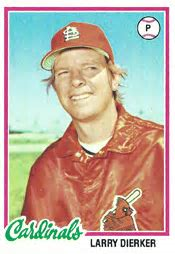

You went to the Cardinals in 1977; things did not go well.

In spring training, I fell when I was running in the outfield and broke a bone in my  left leg. When we broke camp, I still had a cast on it. My arm was bothering me a lot, and I was sensitive that they had traded for me and expected me to win a lot of games.

left leg. When we broke camp, I still had a cast on it. My arm was bothering me a lot, and I was sensitive that they had traded for me and expected me to win a lot of games.

I was kind of happy in a way when I broke my leg, because I got a reprieve and I was going to have another month or six weeks to try to get my arm right. But when I was finally able to run and play, my arm wasn’t any better.

I made a few starts there, but not very many, and they wanted to send me to AAA. Vern Rapp was the manager, and he said to pitch a couple of games there and be ready. I said, ‘Vern, I’m ready to pitch in the big leagues now. Pitching in the minors isn’t going to help. If I can’t pitch here, I can’t pitch anywhere.’

I worked the rest of the year to try to get my arm better. The next spring, it was good enough to pitch, but it was still bothering me and every time I pitched, I got hit. I was really tired of the pain and really tired of the failure.

So finally, Bing Devine called me in told me he was releasing me. He was apologetic, and he thought at my age, someone would surely pick me up. He offered to make a few calls, but I said, ‘Bing, I think I’m at the end. It’s been two years trying to get my shoulder to where I can get people out, and I haven’t been able to. I don’t really want to go through it anymore.’

BROADCASTING

What did you do after you were released?

I had been going to college for a semester each year, and my major was English. I needed four semesters of foreign language and some English courses to complete my degree. I didn’t want to teach school, and I didn’t think I could make a living writing. I had gone to real-estate school, and by the time I was finished pitching, I had a broker’s license. And I did that for about a year.

I also applied for a writing position at Houston City Magazine. I asked them if I could  do a sports column, and they agreed, After two or three columns, it was close to spring training, so my next idea was to go to the Astros’ marketing director – they were terrible at that time, and in bankruptcy. The team was being run by GE Credit and Ford Motor Credit – and do a column on ‘how do you sell a bad team? How do you get people to buy tickets? How do you get people to come out and watch these guys?’

do a sports column, and they agreed, After two or three columns, it was close to spring training, so my next idea was to go to the Astros’ marketing director – they were terrible at that time, and in bankruptcy. The team was being run by GE Credit and Ford Motor Credit – and do a column on ‘how do you sell a bad team? How do you get people to buy tickets? How do you get people to come out and watch these guys?’

During the course of that conversation, the marketing director asked me about ticket sales, and so I said I would be willing to do that if I could get a shot at broadcasting. So they gave me road TV games – they didn’t televise any home games at the time – and they were going to go from four or five road games to 45-50.

So I got a part-time broadcasting job to go along with the ticket-sales job, and that’s what I did for about two years. Then they wanted me to get on radio when I wasn’t on TV. Once I got a full slate of games, I talked my way out of ticket sales, and all I did was broadcast after that.

How difficult was the transition out of baseball as a player?

What made everything easier was that I had a job that I was going to get paid for. I didn’t make any money in real estate, so it was a no-brainer to take the job with the Astros and have a salary.

Could you bring something different to a broadcast? Did you see the game differently?

Maybe a little. I think it helped that I had gone to college. I took three speech classes in college, and majoring in English, I had a better vocabulary than practically anyone else they could have hired. And I was lucky enough to have a decent voice for it.

I think I have qualifications beyond just being a former player; any former player can bring insight to a broadcast, but they can’t all speak in complete sentences, and they don’t all have good voices. So I had some advantages going in. After that, it was like pitching: learn a little more about how to do it better, year by year.

You created a series of podcasts that were different and successful. How did that come about?

The podcasts were a stroke of genius and a little luck. It developed out of my antipathy for doing a pregame interview. The main guy — Gene Elston or Milo Hamilton — would interview the manager, and I would interview somebody, and another announcer would do the third one.

I got tired of interviewing the same guys every time, and having them give me the same answers. So I just thought ‘there’s gotta be a better way to spend three minutes than listen to this same stuff over and over again.’

To augment the broadcasts, I kept a file of ‘things that happened on this day in baseball.’

I had the idea, and I was already writing a column for the Chronicle, so I went to the Chronicle and asked them if they would sponsor [the podcast], and they listened to a couple of sample shows.

The Astros got a sponsor; I got paid for doing it; and I ended up with about 500 of those shows.

MANAGING

You didn’t expect to get the job as the Astros’ field manager.

That was a total surprise. I was a little irritated, to tell you the truth. I had had my arm in a cast, and I was looking forward to the end of the season, so I could get the cast off and just float in a canoe and stick my arm in the water to see how it feels for my arm to feel cool for a change.

But after about a day of that, [President of Baseball Operations] Tal Smith called me into the office, and he said it was very important.

He started asking me about the team: what should we do over the winter? What should we do about this guy? I didn’t think anything of it, because he had done this at other times after I played. About 30-40 minutes in, he said, ‘you have a good grasp; maybe you should be the manager.’

I just laughed; I thought he was joking.

Then, when I saw the GM there, I started getting suspicious. Next thing you know, I see the owner out there, and that’s when I realized that they were going to talk to me about managing the team.

No one had gone from the booth to managing after never having managed at all. At the press conference, the GM said, ‘the Astros have relieved Terry Collins of his duties, and the next manager is here in this room.’ Of course, no one expected it to be me. When they brought me up, everyone was smiling and surprised, and it was quite a scene.

Were there any surprises when you took over?

I didn’t anticipate that there would be as much pressure as there was. When I was in the booth, I was basically doing the same thing: ‘let’s see what the manger does.’ As a broadcaster, when it was likely time to do or not do something, I would lay out what the options were; so I felt like I had already managed.

Being in the dugout, it was a whole lot different.

Did you feel extra pressure because of your long standing with the team?

No, the opposite. Most people who had been Astros fans were curious as to how it would turn out, but they didn’t see why I couldn’t do it. They were hopeful.

But everywhere else, the press would write about how insane the Astros were: ‘this will never work; it’s a grandstand play.’ There was no affirmation, or anything positive anywhere except in Houston – but where it was important was Houston, and I felt people were with me there.

Did that dissipate over time?

Yes. I didn’t mind. I didn’t mind doing interviews. I was probably an easy option, because I could give complete answers. Otherwise it’ s like Daryl Kile after he pitched his no-hitter; you have to ask a million questions, because the guy’s not talkative.

So you could sell the game as well as manage the game?

Yes, I was completely prepared to sell the game. I knew the marketing, because I had been in the meetings. Most broadcasters read the copy, but they are not that familiar with what they are trying to sell.

Four of your five seasons as manager were successful. Is it fair to characterize you as a manager who was old-school, yet had innovative ideas?

In a lot of cases, I had ideas that I thought would improve our chances, but I had trouble selling those ideas to the players.

The hit-and-run was a deadball-era play. The game had developed into a power game going into the steroid era. It was more high-scoring. I was happy to see teams bunt in the first inning with a man on. I will take an out and face the number-three hitter; pitching with an open base was a luxury when I was pitching.

The whole idea to me on defense is to make all the runs earned. Be focused, and be stingy. Don’t make stupid mistakes.

Did you emphasize fundamentals more than other managers?

I probably didn’t emphasize them as much—really a lot of those on offense would go back to deadball era strategies. I had everybody that was fast enough to steal had a green light unless they got a ‘don’t steal’ sign. For instance, if a left-handed pull-hitter was up with a runner on first, I wanted the batter to have that big hole to hit through; don’t try to steal.

I didn’t have anybody bunt until the eighth inning, unless it was the pitcher – or if it looked like one run could change the game.

I probably talked more about defensive fundamentals.

For instance?

I didn’t try to do anything extra to get the double play. I had to keep getting [second-baseman Craig] Biggio to play closer to first; he wanted to cheat toward second for the double play. I wanted him to get to balls that were pulled by a left-handed hitter, and just get the force at second. But I had trouble convincing him of that.

One idea I added in spring training was that if you thought a guy might be running, and you would ordinarily pitch out, pitch in – up-and-in – and the hitter would have to get out of the way and the catcher would be in position to throw.

If the guy wasn’t running, you would at least move the guy back, and they wouldn’t necessarily know you were doing it for the purpose of throwing out a runner; they would just think it was an up-and-in pitch, which at least may have some positive effect on getting the guy out.

When I tried that, the pitchers were unable to execute the pitch with any control.

I was used to doing that when I pitched – it wasn’t a completely wasted pitch if I threw six inches inside and shoulder-high.

In general, did they play essentially the way you wanted them to play?

Yes, for the most part. With them playing hard and having good focus and making smart plays, that kind of set the tone. The only indication I had that we were more efficient in some ways than other teams was that two or three times around the batting cage, a player form another team would come up to me and say, ‘I’m going to be a free agent, and I like the way you play – let the GM know.’

Greatest compliment we could get.

One of your hallmarks as a manager was your approach to the role of the starting pitcher.

You’re getting paid for winning games; you’re not getting punished for losing games. The more innings pitched, the better chance you have of getting the win yourself, and not a no-decision.

You could get the loss, too. If you keep getting the L, you won’t be in the rotation.

But if you are good enough to be in there for 6-7 innings and 100 pitches — even if you are a little bit tired — if they have only scored one run off you, they are frustrated, and they would rather see a relief pitcher come in, because they haven’t had any success against you.

I would rather have them stare the loss in the face and say, ‘the heck with that – I’m going for the win.’ –– Larry Dierker, on starting pitchers

Your teams struggled on offense in the postseason. Was anything different, that you could tell? Or was it just good pitching?

Initially it could have been that some first-year guys who hadn’t been in postseason got a little tense or were trying too hard, but you have to give the pitcher credit too. We faced some guys at their best, but we faced an awful lot of good pitching – and at other times during the season, we hit them. We could have won, but we didn’t.

There’s ebb and flow of the offense for any team – for a week or so, you can’t score runs, then you break out – a whole team could have a streak. We hit them before, but we didn’t in the playoffs.

After five years and four division titles, you were let go. Did you feel that you had done as much as you could?

At that point, the managing wasn’t enough; for some guys, being a major-league manager is enough. But for me, I didn’t love it that much. I really liked the strategic part of getting the best lineup, being prepared for matchups, managing the pitching during the game, and everything that happened from first pitch to last.

What I wasn’t that thrilled about was coming to the ballpark at 1:00 for a night game because three or four guys were already out there. After the first game of a series, I pretty well had my cheat sheet – all the things you need to know to make the substitutions and moves. A third of the way through the season, the numbers speak for themselves.

But being the manager, I felt that it was important for me to be out there when the players were there. Because so many came out early, I had to come out early.

How you manage your time in life is pretty important. I felt like I was wasting time – it wasn’t helping us win. It was just ‘being there to be there’ because you’re in a leadership position. In 2000 [when the Astros finished 72-90] I didn’t like having to answer the questions about being fired day after day.

There were just a lot of things I just wasn’t that wild about. I thought, ‘this is not the ideal job for me.’ I didn’t like to have to do discipline. I also didn’t like it when I had to answer to the owner or GM why I did certain things.

Did you want to manage again?

I didn’t really try to get other managing jobs after I was fired. I did call on two: the Phillies and the Red Sox. My feeling was if I was going to do it again, it needed to be somewhere where they had a great, long tradition of baseball and one of the great, historic franchises.

I did get an inquiry from the Royals, and I said no.

What’s the most-important thing you learned as a big-league manager?

I learned during those five years that I wasn’t born to be a manager. I was capable of being a manager, but I enjoyed pitching, I enjoyed writing, and I enjoyed broadcasting. In all of those pursuits, I don’t have a boss, no one looking over my shoulder, and I’m not responsible for anybody. That’s what I learned from it; I learned about myself.

I may have had good ideas; I may have been able to strategically do a good job managing the game on the field; but it wasn’t a perfect fit for my personality.

So after a couple of days, when they wanted me to resign, I thought, ‘I have all this time off, and they have to pay me all next year. This way, I could go out on top.’ I accepted it pretty readily after a few days.

What motivated you to write your book, This Ain’t Brain Surgery?

I wasn’t sure if I could do it; all I had done was write columns. But I met with Simon and Schuster, and they said, ‘you’ve done a lot of things – pitched, broadcast, managed. That’s three chapters. Then there’s spring training, and umpires, and the rest. Just write an essay on each one, put them in whatever order you want, and you’ll have a book.

LARRY DIERKER TODAY – AND TOMORROW

How is life for Larry Dierker these days?

It seems to be getting a little better.

What happened in my life was that my wife got cancer. She fought it for about a year and a half, and she passed away in December 2017. That occupied all of my time.

I had a couple of years where I was emotionally spent, and I knew I couldn’t go on that way. I wanted to get back in the booth, but the Astros didn’t want me in the booth. After a couple of years, I gave up on that.

That probably was the start of me being out of sorts, because I was clearly the most-qualified, capable, and most-popular person they could have put in the booth; but the new ownership wanted a fresh start and younger mentality, and they just weren’t ready to consider that, so that kind of got me a little depressed.

In general, I am feeling better; a little more like myself again. But I still think there’s an even better feeling that lies ahead.

As long as I can do work that I’m satisfied with, there’s intrinsic value — even if there isn’t monetary value. It’s not so much about trying to make money; it’s about doing something that will have value in an ongoing way.

I feel good about what I’m doing. I’m not working for a boss, and I’m not responsible for anybody.

And you are working on a new book?

It’s tentatively called ‘The Big Boys’ Bathroom Book of Baseball.’ We’re going to serialize it, a chapter at a time, then put it out as an ebook.

What’s it about?

In addition to keeping a notebook on ‘this day in baseball,’ I started collecting quotes about the game from baseball and nonbaseball people—Woody Allen talking about baseball, for instance. I thought a book of quotes would be a lot of fun for baseball fans. You could read it like a magazine – open it in the front, middle, or back — and read it.

I left probably 80 percent of the quotes the way they were; the other 20 percent, I added my own stuff. If was succinct, I wouldn’t have to expand on that.

For instance, Terry Pendleton talked about how he loved fielding, and how it was ‘like dancing with the ball.’

I dedicated the book to Casey Stengel and Yogi Berra. And there will be chapters on fielding, hitting, umpires, cities and ballparks, and The Great Ones.

We’ll put a chapter on the site and leave it there for three weeks or a month, then put up another one. When we have gone through the whole thing, we will put it all together into an ebook.