Eric Soderholm was a first-round draft pick of the Minnesota Twins in 1968. He spent five seasons with the Twins, then signed as a free agent with the Chicago White Sox, where he was part of the famed South Side Hit Men team in 1977. He later played for the Rangers and Yankees before the last in a series of knee injuries ended his career. He was a childhood friend and teammate of my friend Steve Foucault (interview here) and that led to this interview.

As has been known to happen at The Haught Corner, we had so much to talk about that the interview had to be split. Part I deals with Eric’s playing career, and Part II will be about life after baseball, his spiritual journey, and SoderWorld, his wellness center (www.SoderWorld.com).

JH: You played in the big leagues from 1971 to 1980, and I lived in Arlington [Texas] from 1970 to 1980, so there’s a little bit of a parallel.

ES: You’re familiar with my era, then.

JH: Oh yeah! The South Side Hit Men, the Twins, the whole thing. What I remember most about you is tinted shades, bad knees, and a lot of power. Is that a fair capsule summary?

JH: Oh yeah! The South Side Hit Men, the Twins, the whole thing. What I remember most about you is tinted shades, bad knees, and a lot of power. Is that a fair capsule summary?

ES: I would say you hit the nail right on the head!

JH: I guess you and Fookie have a connection that goes way back to when you were both kids in Florida.

ES: Yes. We were playing Little league ball together, and against each other, throughout that time. He was a year behind me, I think. He played third base and I was playing shortstop, and so we developed a nice little friendship. And then we both ended up going to New South Georgia Junior College, which was a very small school, but known for their baseball; they had won the state championship several years in a row in Georgia.

Eric was a good player, but not a premium prospect in high school. I asked him how that came to be.

ES: I was a fairly little guy in high school. I’d just hit little dinky line drives and stuff. There were some scouts who came around, but there was nobody jumping to sign me, or any colleges coming after me. But my [high-school] baseball coach knew the coach at South Georgia, and got me hooked into there with a work-study kind of scholarship program.

And I guess I fell in love with Georgia grits or something; all of a sudden, when I hit college, I started filling out. I started maturing and developing, and the body started getting bigger — and it wasn’t with steroids or anything. It was just naturally getting bigger. So in junior college, all of those line drives were going to the warning track.

I had a couple of real good years in junior college, and I ended up being the Minnesota Twins’ number-one draft choice in 1968.

JH: Up until that time, you were, you were still playing short. Were you the classic playing-short-and-hitting-third kind of guy that good teams have?

ES: Yes.

JH: Did you play other spots besides short? Did you pitch or anything on days when you didn’t play short, or how did that work?

ES: No, I was just always at shortstop, it seemed like. And when I got signed and I moved along to the minor leagues, and I got even bigger, they felt that I would be best suited at third base. They were talking about moving [Harmon] Killebrew to first base, and I was that number-one draft choice, so you can see how I could have been buried in the minor leagues forever, if Killebrew would have stayed at third. But his knees were starting to bother him later in his career, and the Twins wanted to move him to first base. That’s when I got my opportunity to come on up to the big leagues.

JH: When did you make the switch to third base?

ES: After my second or third year in the minors. I just felt comfortable on that side of the infield. Eventually Texas tried me a couple of times at second base and first base, but I always felt uncomfortable, for some reason, on that side of the field. I was way more comfortable at third and short.

Third base was perfect for me, because I wasn’t completely healthy through most of my career, with the cortisone shots and stuff. At third base, you can kind of hide [laughs]. You know, a step and a dive! But you can’t hide in left field, let’s say, if you can’t run down a ball.

JH: You didn’t really have an issue going from short to third? I mean, a lot of shortstops have balked at making that move, because they’ve been at short all their lives.

ES: No. It actually came kind of natural for me. I was on the same side of the infield; I just had to react quicker.

ES: Now, you got Richie “call me Dick” Allen coming up to the plate. And he’s always wailin’ that 38-ounce log, and I was like, Whoa! I think I’ll move back and play a little left field here! [laughs]

JH: Pitch him away, please! I don’t want him to pull that ball at me!

ES: A lot of times, if they hit really hard balls by you, they’d give [the batter] a base hit. Or at shortstop, if the ball went by you a little bit left or right, they might even give you an error.

But I just was always comfortable on that side of the infield, and I had a pretty good arm; I could get it over there pretty good. So it all worked out well. Third base seemed to be my spot.

JH: So it didn’t hurt your ego, moving from short to third?

ES: No, I didn’t even know what ego was back then! For me, it was just trying to do the best I could, and like [Cubs manager] Joe Maddon says, try not to screw up.

Making the Big Leagues: early struggles

JH: In 1971, you got called up the first time, after hitting .275 in AAA, and you got 93 games in 1972, but then you’re back in the minors for the full season, just about, in 1973. What happened there? I see that you hit .188. Were they just saying, “look, your bat’s not ready”?

ES: Quite honestly, I was a little overmatched when I first got up there. I mean, you hit a buck-eighty-eight, you’re not doing too well. But I did pop in a couple of homers, and I showed some potential. But you’re either ready for something, or you’re not.

a buck-eighty-eight, you’re not doing too well. But I did pop in a couple of homers, and I showed some potential. But you’re either ready for something, or you’re not.

I was still intimidated walking into the locker room and seeing Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Tony Oliva — all these stars. Oh, God! Am I good enough to play with these guys now? You have that negative, Do I put my pants on the same way as these guys? attitude. That’s the kind of mentality I had that year, and that showed — obviously — with me hitting .188.

JH: What did it take to overcome that? Was there a moment or an at-bat or a game where you said, hey, I’m going to be okay now?

ES: I don’t think so. I went down to Tacoma the next season, and I wasn’t doing too well. I think I was hitting around .240. But then Killebrew, his knees were really bothering him bad, and so they said, even though Soderholm couldn’t hit his weight last year, we gotta move Killebrew to first; let’s give him another crack at it.

And I think, when I got that second crack at something, now you come in with a little bit [of] okay, I know what this is about, now. You just kind of instantly mature a little bit. You start to feel like you put your pants on the same way as everybody else.

And it did help that Calvin Griffith paid for a guy from a company called Success Motivation. He gave all the Twins players the option of taking this course where you need to set goals. It’s funny: the first thing he made us do was write down 10 or 15 things that you wanted to accomplish in your lifetime. Then we sealed them up in an envelope and he said “sometime in the future — not now, it’s going to take a little while — sometime in the future, look back and check and see where you’re at, and how you’re doing with those things that you just set out the intention, the desire to do.”

Even though I didn’t understand what he was talking about, he was talking about energy back then, but it was not used in those terms. And now I get what he’s talking about, because you’re creating your reality. So if I put out positive vibes, I’ve got a really good chance to get much more positive things happening in front of me. If I’m putting out the negative vibes, obviously, what do you expect to be out there?

So I learned to start thinking better, even back then, through the training from this course that Calvin Griffith paid for. I began to think differently, and it was very helpful.

You start to get a little confidence, and boom! I can do [it] here. I can play here. I can play with these guys. So again, see how we’re creating our own reality. That’s what I know now, and that’s what I teach now.

JH: And you went from hitting .188 to .297. So obviously you turned a pretty big corner there, and you were off to the races after that. Even though the Twins didn’t exactly see fit to compensate you very fairly — making 14 grand a year!

ES: That was the notorious story with Calvin Griffith. They said he squeezed nickels

like, he squeezed the buffalo’s ass, or something like that. I forget what the saying was, but everybody knew he was just so tight.

My first year, $14,000 was the minimum salary, and I got paid the minimum salary. And then my second year, I hit .276, I believe, and I’m still making the minimum salary. And I went in to see him the third year — this is before agents and everything – I’m thinking $25,000 or $26,000, a $10,000 raise.

And you’d have thought I shot him!

Honest to God, he reaches in the drawer, and –-

JH: This is when he pulls out the stat sheet and reads your sins?

ES: Yeah! He gave me ten reasons why I should be making the minimum salary! I said, “You gotta be kidding me!” And I held out for two weeks.

Finally, I got a call from his secretary: “Mr. Griffith has changed his mind. He’s gonna give you a raise.” So I’m all excited, thinking I’m going to get 25 grand. He pushes the contract at me, and it’s for 16 grand. A $2,000 raise.

And he says, “If you don’t take this, you can go sell fish in Miami. We don’t need you.”

I mean, that’s how it was back then. This was before free agency. And then, of course, everything just completely flip-flopped and went on the players’ side of things. Then you got the owners fighting each other, battling each other, outbidding each other to try to get the player they think will help them win a championship. A lot of times they were wrong on that, but they were bidding against each other, and all of a sudden, the salaries started to skyrocket. So I was in that first free-agency pool, with Reggie Jackson and I can’t remember who else.

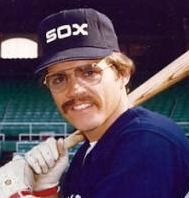

Free agency and the South Side Hit Men

ES: The White Sox drafted me, and Bill Veeck offered me $55,000. I was at $25,000 with the Twins, after five years in the big leagues!

JH: And he took a big chance on you, considering your knee injury and you hadn’t played in 1976.

ES: Bill Veeck was a fan of the underdog. He loved to give people second chances, and he loved to entertain people at the park. And whether we won or lost — I mean, obviously, he wanted to win — he wanted the fans to get their money’s worth. You know, he had trapeze artists out there; he’d have all kinds of shows going on. It was a three-ring circus out there. But I loved the guy.

JH: He did you a solid, for sure.

ES: He did me a solid favor, man. He invested in me, took a chance on me, and I actually told him one time – he was in the hospital for emphysema and a bad back. And when I signed with the Sox, I went to see him.

I walked into the room, and there he was, with his wooden leg propped up on a pillow, with an ashtray in the wooden leg! And the first thing that comes to my mind is, oh my God, no wonder he’s in for emphysema! Seems like, if you had to build an ashtray in your wooden leg, you’ve got a big problem.

We talked, and I told him I was so glad I signed with them. He said, “we’re so glad to have you, because you can play multiple positions. And you’re gonna be a solid utility player.”

ES: And I said, “Mr. Veeck, don’t be surprised if I’m your everyday third-baseman, and have a big year for you.” He said, “If you do that, come see me again in a year. I’ll take good care of you.”

JH: And he did!

ES: He took very good care of me at $55,000. He increased my pay by 30 grand, and he didn’t even know if I was gonna be able to play, when I had that shaky knee! And sure enough, I go out and hit .280 with 25 homers.

And when we came back from New York, there was a note in my locker at the end of the season: “Come see me. Bill Veeck.” I go up there and I see him, and he’s got a two-year contract for me for $300,000. He remembered telling me in the hospital that he would take care of me if I was his everyday third-baseman.

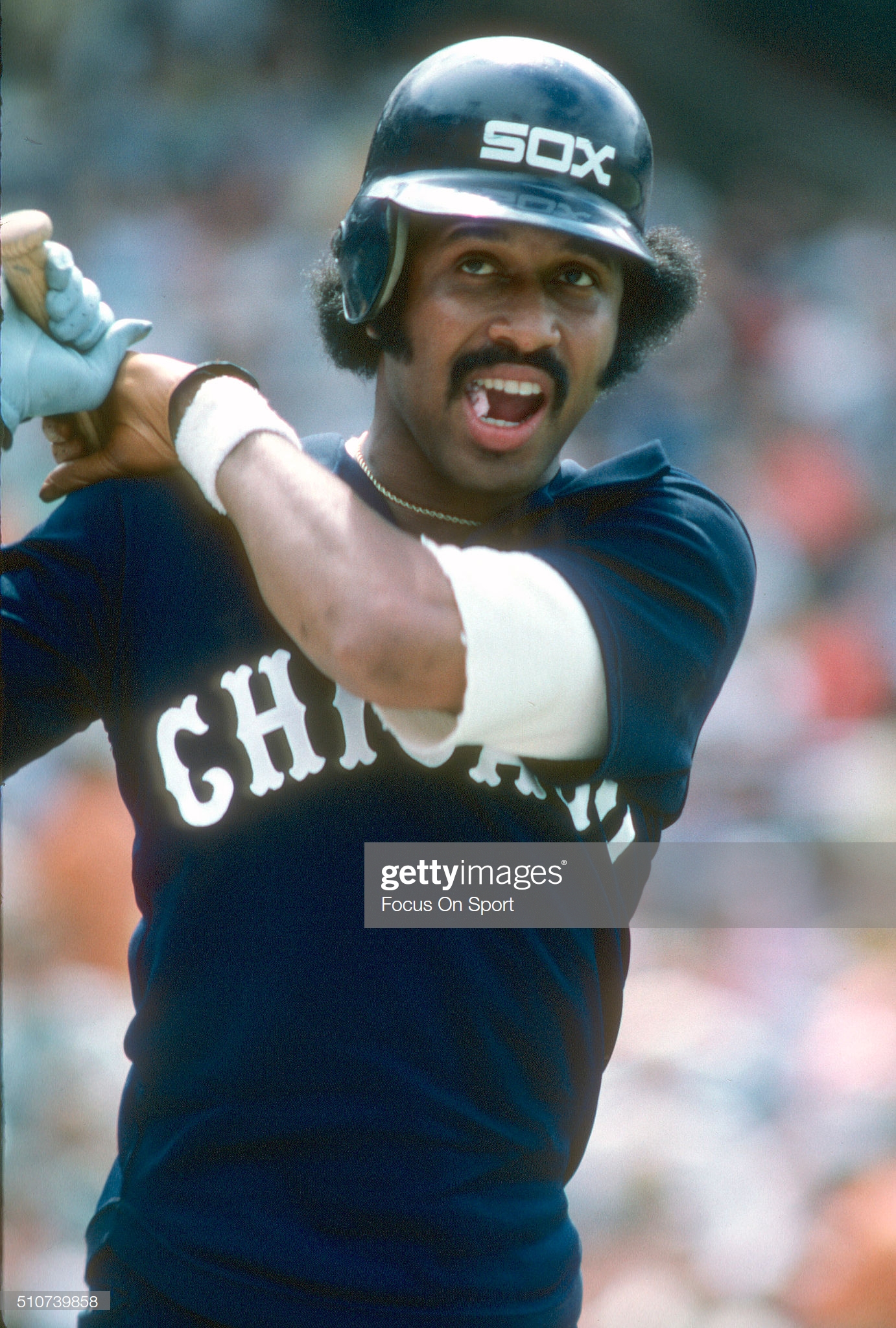

Unfortunately, I signed it and then Richie Zisk and Oscar Gamble, who were a big part of the South Side Hit Men, they took off for greener pastures and kind of left me hanging. It was really bad, because I was hoping that the team would stay together, because if we could’ve gotten another pitcher — I mean, Steve Stone was throwing well, and Wilbur Wood was pretty steady — if we could’ve gotten another decent pitcher, who knows? We might have won.

JH: I hadn’t realized what happened that year until I went back and looked at the roster. I had forgotten, for instance, that that was Zisk’s only year in Chicago; he came to Texas after that. And you’ve got Lamar Johnson and Chet Lemon and all these guys and jeez, no wonder there was a record for home runs. But then I look at the ERAs, and I’m seeing 5.1 and 4.5. And in those days, that wasn’t gonna cut it.

to Texas after that. And you’ve got Lamar Johnson and Chet Lemon and all these guys and jeez, no wonder there was a record for home runs. But then I look at the ERAs, and I’m seeing 5.1 and 4.5. And in those days, that wasn’t gonna cut it.

ES: And Wilbur Wood throwing both games of a doubleheader with his knuckleball! It would have been interesting, if we’d had any kind of pitching.

The South Side Hit Men were fun to watch, but they cooled off down the stretch, and Kansas City won the division title in 1977.

JH: It just couldn’t hold up down the stretch? And the Royals went past?

ES: Well, we went 15-15 in our last 30 games. It wasn’t like we folded, but Kansas City went 24-6 or some crazy thing. I mean, they got really, really hot — especially after the big four-game weekend series we had with them.

We kinda did the “Na-na-na-na, hey hey, goodbye!” thing, and the tipping of the hat, and that was taboo! That wasn’t ever done in baseball before, to the extent that the South Side Hit Men were taking curtain calls and bowing and tipping their caps.

And so [the Royals’] Hal McRae hit a home run and literally walked around the bases, mimicking the tipping of the hat. And he was trying to make us look like we were hillbillies or something.

But after that point, we just kind of got flat. I mean, we didn’t choke, but we just didn’t have the same zip that we had earlier in the season. But to have a five-game lead in late August, when you were 100:1 in Las Vegas, that was pretty exciting.

JH: I tell you what: it was a lot of fun watching that team. I loved watching you guys, because it looked like every game was like a street fight, and I would not normally have been one who would go for Nancy Faust up there on the organ doing that [“Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye”]. But I thought that was absolutely hilarious. It was against my nature, but oh my God, that was funny.

ES: Yeah, it’s funny because I know even today, and it’s what, 40, 42 years later —

JH: Well, it was original. Nobody else was doing that.

ES: And you’d be surprised how many people come up to me and say, “that was one of the most exciting, fun baseball seasons I have ever experienced.” And that does make me feel pretty good. It was a magical kind of year, for sure.

JH: Before you signed with Chicago, were other teams keeping an eye on your rehab? I know that Nautilus thing was a big deal: that you were working with them and they were gonna promote your comeback. But that was so new then.

ES: I had a deal with Nautilus that if they would rehab my knee — Calvin Griffith wanted me to rehab the need at the place where the guy did the surgery, and who I thought screwed it up. I didn’t think he did a good job on my knee, removing the meniscus and cutting it in half; it still left it very weak and vulnerable in there. And [Griffith] wanted me to rehab it there.

Nautilus found out about it and said, “look, we’ll rehab you for free, if you allow us to use your name and stuff. And if you come back, we’re gonna promote Nautilus,” which was very new on the market. Dick Butkus and myself were the celebrities, or so-called celebrities, who were helping to get Nautilus on the map. And so they rehabbed me almost daily to the point where some days I was just throwing up, I was working so hard.

ES: It was just a powerful experience to realize how strong I could get without steroids and stuff by really pushing myself. And I had never pushed myself to that level.

Sure enough, I came back, felt great. I had a great year, and Nautilus flew me in the wintertime, all over these different conventions. I was there kind of their spokesperson, along with Dick Butkus, about the value of weight training and hypnosis, which was taboo back then.

I was wanting to let everybody know the benefits of training hard, and I was using a friend of mine, Harvey Misel, who was a hypnotist out of Minnesota. I was staying in a positive frame of mind, through his help.

It’s mind, body, and spirit. You need the combination of all three to become the best player you can be. I wish I’d have learned all that back then; I would have been a better player if I knew then what I know now. Wisdom comes with age.

JH: Were there other teams following you while you were doing your rehab, that might have given you an offer? Or was it pretty much the Sox?

ES: I was drafted by four teams; Kansas City was one of them. I admired Kansas City’s team, too. George Brett was one of my favorite players to watch play. Texas, Chicago, Kansas City. I don’t remember the fourth team, but Bill Veeck was obviously the one that pursued me with the most vigor.

JH: You would’ve had a hard time in Kansas City with Brett at third; that would’ve been a tough fit.

ES: And in New York, Graig Nettles was there. So what are you gonna do? Although I did end up going to New York [in 1980], and I DHed for them for a while. But Nettles had a lock on that position, for sure.

1978: Slow start and a wakeup call

JH: You talked about some of the guys leaving after 1977, and that I’ve read also where you really struggled in the first part of 1978 until you were able to turn it around later. You ended up with fairly decent numbers, but apparently it was quite a struggle early on.

ES: Yeah, it was a horrible struggle to come off a year where you win the Comeback Player of the Year Award, and you’re on the fried-chicken circuit. All winter I’m out three nights a week speaking, signing autographs, and I let myself kind of get out of shape.

We were just talking about how hard I pushed myself with Nautilus to be in shape, and now I’ve experienced the fame. So now all of a sudden it’s hard to stay as motivated as you were, to stay there. You get kinda get lazy, I think. “Oh, it’s no problem. I can go rush through this, and no problem.” But you find that you can’t, if you don’t have that level of intensity and that desire.

JH: And you got shin splints, right?

ES: Yeah! I went to spring training out of shape; figured I could get in shape in spring training. Third day of spring training, I got these terrible shin splints on both legs. I missed a big portion of spring training, just trying to get well and for them to heal. Because I had such a good season the year before, they obviously gave me the job at third. And so I started, and I wasn’t ready. I opened up the season and was not ready, Kinda like the first year with the Twins.

I just mentally wasn’t ready, but I struggled through and I got about a third of the way through the season, and I’m hitting, like, .204 with four dingers. It’s just not going well. And I had some very bleak moments. Was very depressed.

But the thing that woke me up was an appearance at the Illinois Masonic Hospital. I had promised I’d go down there and sign autographs for these kids who were dying of cancer or leukemia. I went down there, and boy, to see these kids smile, with these circles under their eyes, just by signing an autograph, they seemed so upbeat.

And then they took me into the basement where the kids were in wheelchairs and they put me in a wheelchair, and I played a wheelchair basketball game with these kids. And was over, I just unbuckled the safety belt and got right up.

Then it hit me that none of the kids I was with could do that; they were gonna be confined to their wheelchairs for the rest of their lives. It was like I got gobsmacked: WAKE UP!

I went to the park that night, and I didn’t change anything except my attitude; I was grateful for the opportunity. Any of those kids I saw would have paid anything to be in my shoes. And here I was, sulking. They woke me up.

I even hit a home run that day, and I started to turn it around. And I went from .204 and brought it all the way up for that up to .258, which — raising your parents 55-60 points, you’re doing some hitting.

JH: Especially when the season’s half over.

ES: And I went from four home runs to 20. I had 16 home runs the second half of that season. I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for those kids who really woke me up that day.

season. I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for those kids who really woke me up that day.

JH: And it had gotten so bad, I understand, that at one point, you actually had an anxiety attack against the Red Sox in the batter’s box.

ES: I was standing in the batter’s box, and all of a sudden my knees are shaking, and my hand started shaking. I thought, God, can anybody see this? It was like I was outside my body: can anybody see my hands shaking or my knee shaking? I was having an anxiety attack. It was a mild one, but nonetheless, an anxiety attack.

I didn’t even swing the bat. I struck out, and boy, you get booed by a bunch of people, it’s not a pleasant thing.

JH: I’m sure it wasn’t; that’s gotta be tough.

ES: No fun. But I had contemplated — you know, I was very depressed, and you think bad thoughts when you’re depressed. And I just I had a lot of bad thoughts running through my mind, and [was] trying to figure out how I could hurt myself or something and get out of the lineup and stuff, and then boom! that appearance showed up, and it completely woke me up. And that’s just incredible.

JH: You mentioned Dr. Misel, the hypnotist. When did he start playing a role in your career?

ES: Probably 1973 or 1974.

JH: So that was earlier.

ES: Yeah, it was earlier. And then I hurt my knee, and he helped me. I knew him very well during my career with the White Sox. He even came when I was with the Yankees, while we were in the playoffs — he flew to New York. And you know, we worked with hypnosis before those playoff games. I went one for six; I didn’t do all that great, but I felt good. I mean, I really felt good. I just missed some pitches from, like, Paul Splittorff that I usually would hit out of the park.

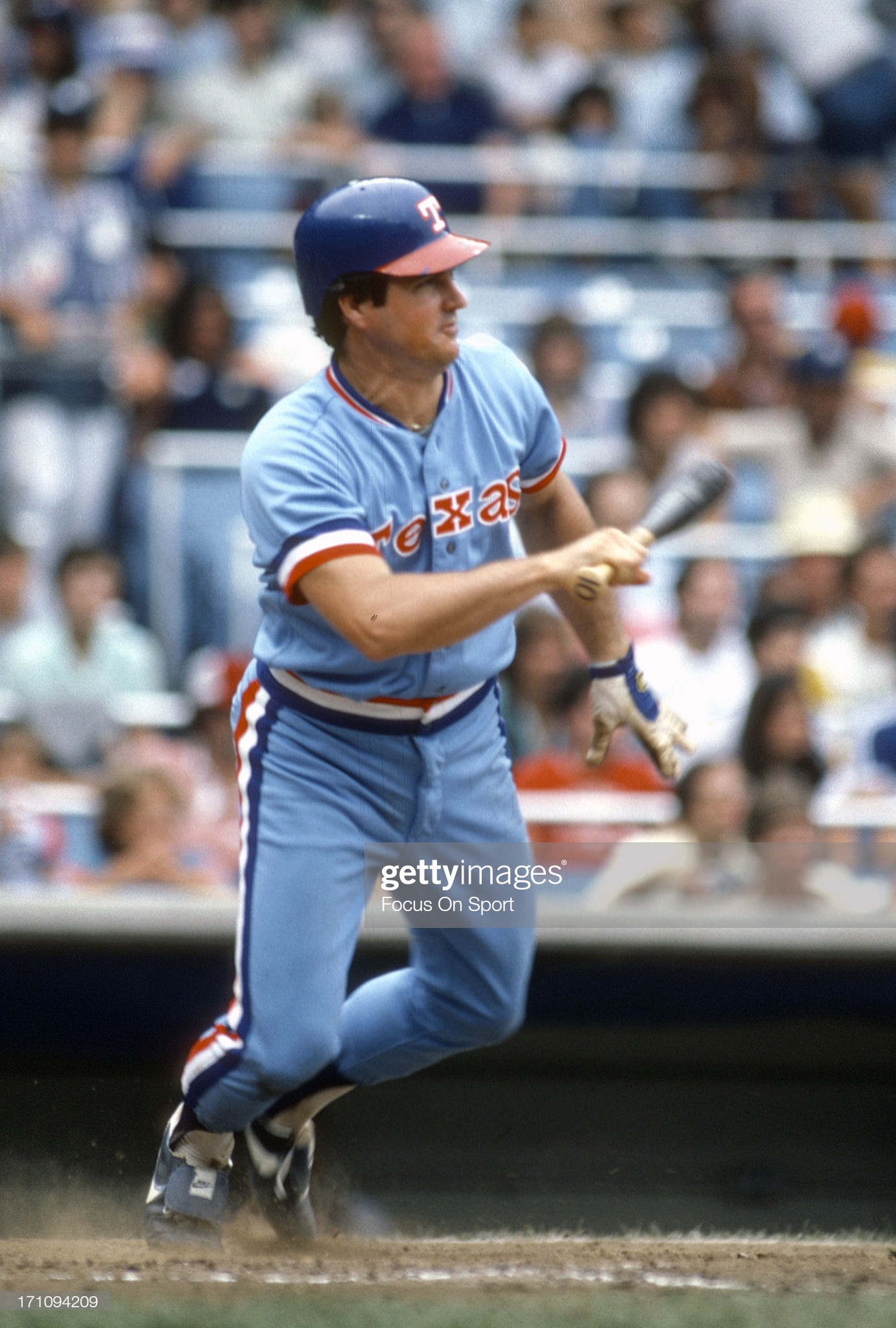

1979: Traded to Texas

JH: I had forgotten that you were traded to Texas in 1979, basically for Ed Farmer.

ES: We swapped houses! I went down and lived in his house. He came and lived in my house, and we just didn’t pay each other rent.

JH: But it was only a half-season, right?

ES: About a third of the season.

It was painful to go, because I really felt comfortable in Chicago, and the fans seemed to like me. It’s just that Bill [Veeck] just didn’t have money to make up for the loss of Richie Zisk and Oscar Gamble. To go from that kind of peak season to the next year, you’re losing 92 games, it’s quite a downer. And it was really fun going to the park every day in 1977; couldn’t wait to go. In 1978, just a year later, it was hard to go to the park; we just didn’t have anything going.

the loss of Richie Zisk and Oscar Gamble. To go from that kind of peak season to the next year, you’re losing 92 games, it’s quite a downer. And it was really fun going to the park every day in 1977; couldn’t wait to go. In 1978, just a year later, it was hard to go to the park; we just didn’t have anything going.

He brought in Ron Blomberg. Bobby Bonds when he was in the twilight of his career. You just can’t make up for the loss of 60-some home runs from Zisk and Gamble with Blomberg and Bobby Bonds; it just wasn’t gonna happen. And we didn’t have strong pitching anyways, so it was just so difficult that year. Wow.

JH: But just the one part of a season with Texas, and then you moved on again to the Yankees?

ES: Yeah. Texas offered me a three-year deal to stay there, and I was going to take it. It was decent dough, but my wife just couldn’t stand the heat.

was decent dough, but my wife just couldn’t stand the heat.

When I got there on that [Texas] trade, it was the first day of like 16 straight days over 100 degrees. And I lost seven pounds that first week I played there. And in the backyard of Ed Farmer’s house, it was a desert kind of thing; there were scorpions and bugs and everything. And my wife hates bugs! She just didn’t ever like Texas for some reason, and so we turned down the three-year deal. And when I turned that down, they just traded me to the Yankees.

The Yankees gave me a one-year deal for about $225,000, and that’s the most I ever made. And then the next year I hurt my knee in a freak accident in a charity soccer game, and my career was over.

I got one big year with the Yankees of $225K, but most of my years – the first five or six — were $25,000 or less. But it’s all relative, and it worked work well for me and my wife.

JH: The guy I always think about in Texas, trying to deal with that heat, was [Rangers catcher] Jim Sundberg. I mean, he’d hit August, and they were catching him every day in that heat. And his batting average would drop 50 points in the last month-and-a-half, because he was just wiped out.

ES: I have a funny story with Jim Sundberg; he was a good friend of Steve Foucault.

When I came to Texas, Steve would have me over for dinner, and Sunny and his wife would be there, and we developed a little bit of a friendship — a buddy kind of thing.

He came up to me the last game of the season one time and said, “Sod, I got a favor to ask of you. I’m hitting .249, and you know how bad hitting .249 looks on a bubblegum card, compared to hitting .250?” And I kinda laughed and said, “yeah, I kind of see that. But what’s that got to do with me?”

He said, “I already talked to [manager Pat] Corrales. He’s gonna lead me off. I’m going to lay down a bunt, and you just play back and let me get my base hit. And I’ll have my .250 batting average, and he’s gonna pull me out of the game.”

I said, “well, that’s pretty nice, Sunny, but what’s in it for me?”

He said, “I tell you what: if you hear me say, “Sod,” it’s gonna be a breaking ball from Fergie Jenkins.” And Fergie Jenkins has the nastiest breaking ball you’ve ever seen in your life; I had trouble hitting that sucker.

So Sunny comes up for the first at-bat, and I’m playing short left field! He lays down this bunt, and it’s just beautiful. It’s right down the chalk line, so I can have no play on it anyway. It rolls all the way to the base and hits a little pebble or something that throws it to the left a little bit and it misses the corner of the bag.

So now I can’t play that far back; I played somewhat in. He still tries to bunt, and he pops it up!

Now I come up to bat, and I said, “one-for-two and you still get there.” He says, “yeah.” And he said, “All right, Sod,” so I knew a breaking ball was coming. And I launched it into the left-field seats for a home run!

So he comes up the second time, and I’m playing back. And sure enough, he tries to bunt, and bunts it right back to the pitcher instead of third base. So he’s oh-for-two and I come up, and he still said, “Sod,” and I hit a line drive into center field for a base hit, and I’m two-for-two.

He eventually goes one-for-three, and with that many at-bats, it’s questionable whether it will raise his average enough. So he tries it again, and he fails. So I came up again, and I hear nothing from behind the plate. I looked back at him and he says, “the deal’s off, man! I can’t hit .250; the deal’s off! You’re killing me!”

1980: A final knee injury

JH: Your last year was 1980 with the Yankees; they lost to the Royals in the playoffs, and all that. And then you hurt your knee trying to score on your “personal buddy” [and former White Sox broadcaster] Jim Piersall in a soccer game, and tore a couple of ligaments?

ES: Well, I had a revenge thing going with him. He called me out one night. I was on first base in a 0-0 game in the ninth inning, and he screamed at [manager] Bob Lemon, “I can’t believe he’s not pinch-running for Soderholm! It takes three base hits to score him from first.” He said this on the air, and so of course my phone lines lit up like Christmas trees, with everybody telling me, “did you hear what Piersall said?”

So I confronted him the next day at the batter’s box, and I said, “Jimmy, come on. I know I’ve had knee surgery, but I don’t clog up the bases.” He goes, “shit, I can beat you!” And I go, “what? You’re a fifty-year-old guy who’s had a heart attack. How are you going to be me?” He says, “I want to race you for $100. Let’s go. Make it $1,000.”

The reporters are all around, eating this up; they love that kind of controversy. And I said, “a thousand? I don’t have a thousand on me, Jimmy, but let’s go down to the warning track and race, right now.” He says, “oh, no, no. We’re going to time ourselves around the bases, because when you got to turn left on your bad knee, that’s where I’m gonna make up ground.”

And I said, “fine. We’ll time it around the bases. Come to the park early tomorrow; I’ll bring my thousand. You bring yours, and we’re racing.” And so I get to the park with my thousand dollars, and there’s a note in my locker from Bill Veeck: Come see me before you put on your uniform. I go up to his office and he sees me, and I go, “Mr. Veeck, is this about the Jimmy Piersall race?” Because it was in the paper that next day.

And Bill says, “Yes, it is about that, and I’m putting a stop to it.” And I said, “why? He says, “well, if you beat him, they’re gonna say you beat a fifty-year-old guy with a heart attack. Big deal. If he happens to be faster than you, don’t you realize he’s on the mic all game long? He’ll tear you a new ass and run your ass out of town!

“And the third thing is, what happens if you pull a muscle trying to beat him in a race? Now I’m [screwed]!”

And I said, “Mr. Veeck, I am so sorry that I didn’t even think about that. I apologize. We’ll call the race off.” Which we did. But we had this little antsy kind of a revenge thing. It was just an uncomfortable thing whenever I saw him.

Fast-forward four years. I’m now with the Yankees. We went to the playoffs, had the best team, but we lost. But next year, I know we’re going to go to the World Series, because we got a dynamite team.

I’m in top physical shape, I get a phone call, and I was asked to be in a charity soccer game. I’m a sucker for charity games. I was a little bit late; the teams had already been picked. And the goaltender on the opposing team was Jimmy Piersall! And I thought, “I wish they could just give me the ball, right in front of the goal. And I’m gonna drill this bastard!”

JH: [laughs hysterically]

ES: The universe gave me my wish: here comes the ball. Somebody kicked it to me; I’m less than 10 feet away from it. I’m going to drill him! And I look up before I go to kick the ball. I see his eyes getting wide as saucers, because he knows he’s about to get drilled.

I took my eye off the ball, and when I went to kick it, I hit the top half of the ball, lost my balance, and went down and tore my anterior cruciate ligament — right in front of Jimmy Piersall. It ended up ending my career over a charity soccer game, trying to get revenge against him.

The Buddhists have a very interesting saying: if you’re going to hang on to the energy of revenge, you might as well build two graves: one for them, but also one for you. I lived that.

JH: You dug your own grave there.

ES: Yup, I did. It doesn’t pay to try to get revenge. That’s the moral of that story.

JH: But the Yankees held onto you through 1981? Or did you spend 1981 rehabbing?

ES: I was trying rehab and come back from it again. But I think George Steinbrenner just got fed up with not knowing if I was going to go play or not. It was just like it was in 1976, so they gave me my pink slip.

Then Dallas Green gave me an opportunity to try out with the Cubs in spring training, and I went, but it was very evident within about two, three weeks that my knees were not going to hold up. There was so much pain in them, and I was tired of taking cortisone shots to kill the pain. So I just decided to hang it up. And I got into the baseball-camp business right away; the only thing I knew how to do was baseball.

JH: That’s a shame, that it ended that way.

ES: But you know, I just had a blast! I had a great career, for being on bad knees. Nine-and-a-half years. Could I have gone longer with good knees? I think so, but I can’t look back and say what if? I’m just very thankful for that time I had, and it really opened up a lot of doors for me in the business world.

So I’m very thankful for my time — and quite frankly, the pension I make. I make more with my pension each year than I did my first five years in the big leagues! [laughs]

In Part II we will look at Eric’s life after his playing days, including his legacy project, SoderWorld.