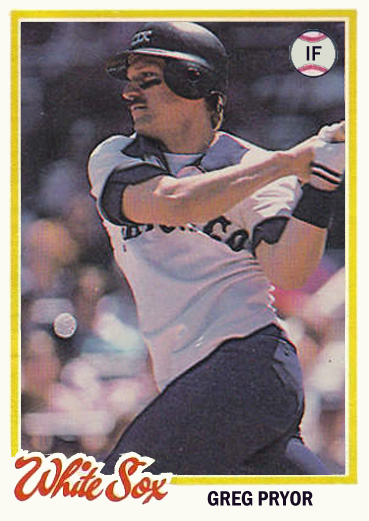

Greg Pryor was only with the Texas Rangers for a short time in 1976, but I remember him from the days of watching games from the bleachers at Arlington Stadium ($2 a seat and a buck to park!). Greg went on to bigger things with the White Sox and Royals, and he was part of the Royals’ first World Series-winning team in 1985.

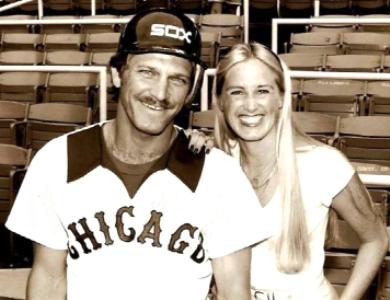

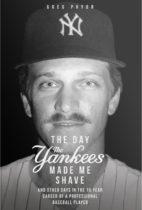

These days, Greg and his wife Michelle operate Life Priority Health and Nutrition, Inc., a  nutritional-supplement firm (lifepriority.com) and his first book, The Day The Yankees Made Me Shave, will be published in October 2018 (preorder at thedaytheyankeesmademeshave.com).

nutritional-supplement firm (lifepriority.com) and his first book, The Day The Yankees Made Me Shave, will be published in October 2018 (preorder at thedaytheyankeesmademeshave.com).

You’re from Marietta, Ohio, and your father encouraged you and your brother to play all sports. When you were in Little League, he even built mounds for the two of you, so you could learn how to pitch?

Mom and Dad grew up in West Virginia. He moved us to Akron, Ohio in 1956 or 1957, teaching school and coaching. He built mounds and plates for us. He would get home from school and have us start pitching on our personal mounds. I pitched in Little League and high school, until I gave up pitching for hitting.

And you were a second-baseman in high school?

Yes, I was small: 5’7” and maybe 140 pounds. Too small to play football, and too short to play basketball. But I was good enough to play second base on my high-school team, and in college.

Second base wasn’t your first choice, though.

I always wanted to play shortstop. Then when I signed professionally, I got the chance to play short, and I played there some in the big leagues. Short was always my love; I enjoyed the other infield positions, but I always loved playing big-league baseball at shortstop.

Having started as a pitcher, you probably had a good-enough arm to play short, didn’t you?

I don’t know. The high-school coach told me, ‘I can’t have you pitching and playing second base; you’re going to have to choose one of them.’ He made me into a second-baseman my junior year, because I could hit a little bit. I really don’t know how I would have done as a pitcher, but I’m so glad that he forced me to choose, because I wanted to play baseball every day.

I would have made a huge mistake if I had tried to be a pitcher.

I really didn’t get a good arm for professional baseball until [Rangers manager] Billy Martin came to Instructional League in 1973. He was telling me how to turn double plays at second base. He says, ‘Pryor, you gotta get a stronger arm.’ So if Billy Martin was telling me that, I went out and got a stronger arm, because to play shortstop in the big leagues you have to have that. And eventually I did have a real good arm.

The stereotype of a second-baseman in those days was a shortstop who didn’t have a strong arm.

It’s more even than that; I was really a below-average infielder most of my life. I think the college coach didn’t want me to play short because I wasn’t that good defensively. My second full season in the minors, I made about 50 errors in A ball, so obviously I wasn’t that good of a fielder. I don’t remember how many of those errors were fielding and how many were on throws, but an error is an error.

In college, I think they were trying to hide me over there.

You suffered a serious shoulder injury in summer ball. What happened?

I was playing second base in summer baseball for Harrisonburg, Virginia. My brother was a pitcher on the team. He got the general manager to let me play on that team after my freshman year of college at Florida Southern.

I was playing second base and my brother was pitching, and there was a ground ball to my left. I dove for it, and my left shoulder dislocated. The large bone that goes into your shoulder came completely out. I went to the hospital, and the doctor popped it back into place.

Three weeks after it happened, I went back for a checkup, and my shoulder was numb. And the doctor looked at me and shook his head. I asked what was wrong, and he said, ‘son, you tore all the nerves in your shoulder, and you have a dead shoulder. There’s no muscle contraction, because the nerves control the muscles, and you’re going to have to put your arm in a sling or tuck it into your pants for the rest of your life. It’s just a dead shoulder right now.’

It shook me to my core; one of the worst bits of news I had ever had. I wondered how I was going to play golf. Golf was my love; baseball was something to get by.

But your shoulder did recover – at least, to a point.

I went back to Orlando and started doing what I could to help my left shoulder. I brushed my teeth left-handed; I started eating left-handed. It wasn’t easy, but luckily for me, some of the nerves started to heal. I lost a couple muscles in my shoulder because they died, but in the big picture, it was a small problem for me.

It didn’t really heal 100 percent; it’s never been a great shoulder, and that’s one of the reasons I made so many errors in 1973, because I just didn’t have the coordination with it. I worked and worked and worked and caught thousands of ground balls, and eventually I got the knack for catching ground balls, to the point that my fielding became my strongest point, even though I wasn’t an easy out.

So in rehabbing, you also developed your ability to field.

Yes. It was probably the toughest thing I have ever done. When you make 50 errors in 140 games as an infielder, you’re really suspect.

Hal Keller, the Rangers’ farm director, told me over the winter after I hit .293 in 1973, ‘Pryor, we really don’t know what we’re going to do with you. Number one, you can’t field; you can’t run – you have no speed; and you have no power. But you can hit a little bit, so we don’t know what we are going to do.’

So I thought to myself, ‘I’m not fast enough to play the outfield, so where’s my future gonna be?’ Well, my future was going to be as far as my fielding took me. So I just went out and mastered the art of fielding. I worked at it.

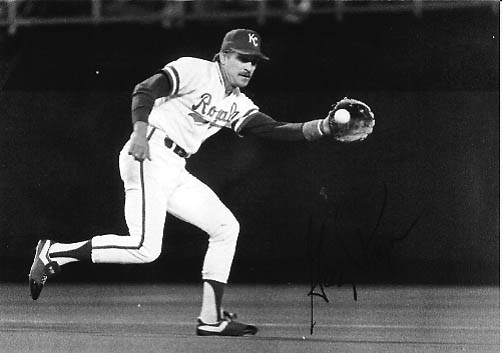

I never dove for balls much in the big leagues, because I had visions of dislocating that shoulder again, but I improved my feet quickness; I became an extremely quick-footed fielder. I could get jumps on the ball as well as anybody, and I had good range.

A number of infield instructors have told me that good hands begin with good feet.

Once you catch enough ground balls, and you miss enough of them, the game will dictate whether or not you’re good enough.

Once you catch enough ground balls, and you miss enough of them, the game will dictate whether or not you’re good enough. I got to where I wasn’t intimidated by any infield where I played; I caught 96 percent of everything hit to me, and that’s enough to keep you in the big leagues.

When you have size-13 feet, and your feet are too big and too clumsy, you really need to work on your feet. I used to open up wounds on my ankles; when I crossed over to catch a ground ball, I would catch the insides of my ankles and split the skin open.

So It was a combination of improving my feet, getting the coordination with my left arm, and improving the transfer of the ball from the glove to the hand.

The big leagues

You were called up to the Rangers in June 1976 – the last position player drafted by the Senators to make the big leagues. And you went 3-for-8. What do you remember about your debut?

I went to spring training before the 1974 and 1975 seasons, so I was kind of like a veteran of major-league spring training. I went down there and I saw these great big-league infielders close up. But in the 1975 season, I got hurt the last game of the minor-league season in Spokane.

Then I wasn’t invited to spring training in 1976, and when I asked about it, the farm director sent me all of the scouting reports on me from 1975, and they all said my tools were short and I was a AAA player at best. I was about 26 at the time, and headed back to AAA in Sacramento as the shortstop. I got kind of scared, so I got busy – really active — for about 90 days.

Bump Wills was the second baseman; Brian Doyle was the third baseman. I played short there for Rich Donnelly, and we were in Tucson in early June, and Rich called me into his office and said, ‘Pryor, I got good news and bad news. The good news is, you got called up to the big club, and suit up tomorrow night for the game. The bad news is, you are coming back here after two weeks because someone is on the DL, and when they come off, you’re coming back.’

When he told me that, it was like, ‘no big deal. I’m going to the big leagues! I’m finally going to the big leagues!’ Mind you, in February of 1976 I got all those bad scouting reports, telling me I wasn’t good enough. Four months later, I get called up.

It was such a thrill to prove them wrong, because when I got called up to Texas, I played with Jeff Burroughs and Tom Grieve, Gaylord Perry, Jim Sundberg, Mike Hargrove.

My first start was against Mark Fidrych in front of 40,000 people. Bert Blyleven had just gotten traded from the Rangers to the Twins, and I started at second base, and I was 0-4 against Fidrych. But It was a big thrill to have my first start in front of that many people.

It was the first time I had played second base in two years. [Manager] Frank Lucchesi came up to me before the game and said, ‘Pryor, when’s the last time you played second?’ And I said, ‘a couple years ago.’ And he said, ‘you can handle it, can’t you?’ And I said, ‘yes sir.’ I had no choice [laughs].

I stayed up for 19 days, and they came to me and said they were sending me back. It wasn’t upsetting to me, because they had told me I was going to get returned. But what really hurt me was that they didn’t call me up at the end of the season. That really got under my skin: ‘wait a minute. How am I not good enough to get a callup, so I can go up there and show them I can play shortstop?’

I could have been the Rangers’ shortstop, had they kept me. But no, they traded me to the Yankees.

You hit .275 at AAA in 1976, but you didn’t get called up in September. That’s not a good sign.

I wish we could go back to the Rangers and ask them why they didn’t call me up. Obviously I was good enough to play in the big leagues; look at my baseball card. Someone else saw my value.

I played four years for the White Sox, and five years for Kansas City. I was good enough to play for the Rangers. I was hurt when they didn’t call me up, and I was very hurt when they traded me to the Yankees in the spring of 1977, because I really wanted to be a major-league Texas Ranger. I wanted to show them that I could play. But that’s not the way my career went.

I just wanted a chance, and I worked so hard.

But going to the Yankees wasn’t the break you wanted and needed.

I got traded to the Yankees and Billy Martin in February of 1977, and here I am in Ft. Lauderdale with Reggie Jackson and Catfish Hunter and Thurman Munson. I’m right there, ready to make that 1977 Yankees team, and Billy Martin didn’t even act like I was alive. He gave me seven at-bats, and I went back for my third year in AAA.

I was 28, and I was desperate to get away from there, because I knew I wasn’t going to replace Graig Nettles or Willie Randolph, but at least I was a better player than Fred Stanley; I was a better player than George Zeber, who was on the 1977 team as a backup infielder; I was a better player than Brian Doyle, who played on the 1978 world-championship team. But look at the stats: I survived all of them. I played nine years.

In AAA in 1977, you hit .271 and stole 10 bases; that should have been a good barometer of whether or not you could play, given your previous years in AAA.

I’m proud to say that I was consistent, even though my fielding needed to improve along the way.

The time I spent in AAA was a damn good apprenticeship. As I look back, I’m kind of glad it happened the way it did, because I see young guys [today] who are called up, and they don’t really know how to play the position.

You can’t really call yourself a major-league infielder until you play enough games and have enough chances to show the world that you are good enough to play.

I was the kind of player that I guess you had to see me play every day to appreciate the small things of the game. I was a good baserunner; I knew where to throw the ball and when to hold the ball. That’s part of the game that I think is being lost.

When I got called up in 1976, my first road trip was to Baltimore. I was able to see an Earl-Weaver-managed team. And I was able to see Mark Belanger and Brooks Robinson.

When I saw those guys and that team – the Orioles had some great teams – people said it was because of their pitching. No, it wasn’t; It was because of their defense. They didn’t give a team an extra out. The great teams take advantage of teams that give the extra outs. When I saw those Weaver teams, I saw the reality of the big leagues: don’t give them an extra out. And that’s how I approached my job.

When the ball was hit, I wanted the damned thing. I went after it with reckless abandon.

What I did to play as long as I did, I treated every play like I was going to get my team off the field, get the pitcher off the mound, because he only has so many pitches in his arm. When the ball was hit, I wanted the damned thing. I went after it with reckless abandon. I wanted to get the guy out as soon as I could.

With that aggressive and positive approach, and the sheer volume of work you put in to improve your fielding, you can see how it could pay off.

Defense and pitching is what every major-league team wants. If you have offense, that’s great; but give me a team that catches and pitches, and I’ll show you a potential winner.

Each infield position has a different mindset to pay defense. At third base, you don’t charge as many balls as you do at short. At short, you really have to be aggressive and charge balls. At third base, the ball comes down there at 120 MPH sometimes; you can’t charge it, so you really have to change your mindset when you play all four of them. At third base, I learned how to back up on balls as well as I did charging them; you can make some plays easier by knowing when to back up real quick and get the good hop. At short, you can’t back up much.

I’m so happy that I got a chance to play all four positions.

Was learning the positioning and different angles a difficult adjustment?

Well, I played second base in college, and that’s probably the easiest position in the infield; it’s even easier than first base. When I got into pro ball, the Rangers wanted to find out if I could play short, so they put me at short in 1973, when I made the 50 errors. Still, I found out that I could play short.

When I got to the big leagues, I hadn’t played much third base, but Tony La Russa wanted me to play third, so I played it more in the big leagues. I learned how to play third when I was with the White Sox. And I learned more about playing short and second. So again, it was kind of like an apprenticeship – the art of how to play each one of them.

You can’t hide; the bench knows if you should make the play.

Did you always have soft hands, or did that develop as you took all those extra reps?

I guess they probably came hand-in-hand. When you position your feet correctly – when you don’t have to dive for balls – when I quickened my feet, it softened my hands.

You also learned about the importance of a good glove.

When I was in spring training in 1973, we played the Orioles. Brooks Robinson used to throw his glove behind his position – leave the glove on the field. One game, I was standing on the sidelines near his glove. ‘Oh, my gosh! There’s Brooks Robinson’s glove. This might be the only chance I have to put it on.” So between innings, I walked over and stuck Brooks Robinson’s glove on my hand – just to see what it was like to have a big-leaguer’s glove on my hand.

When I put that glove on – which was really, really a bad thing to do – I was getting ready for someone to yell at me. But I said ‘screw it. I’m just gonna go do it.’ So I put it on, and I never wanted to take that glove off. His glove was so beautiful! The pocket was so beautiful!

He spit-shined the outside of it black – the inside was brown — and he polished it. And he cut the laces off, right down to the nub. There was no excess leather on Brooks Robinson’s glove. When I saw that glove, I said, ‘If only I had this glove, I could be a great fielder.’

I learned that to be a great fielder, you have to find a way to keep the ball in your glove, to begin with, and you have to break in your own glove – no one else should do it.

When I got to the Yankees in 1977, I learned about gloves from Graig Nettles, because I looked at his glove when I was there, and I also looked at Fred Stanley’s glove. They had wonderful gloves, and they gave me tips on how to make my glove better, along with Don Kessinger. He was player-manager with the White Sox when I was there.

I was blessed with good hands to begin with, and that really helped my fielding.

So you had soft hands all the way through, then?

I guess you could say that I had soft hands and hard feet, at least in the minor leagues. It all developed over time and repetitions.

Did your hands relax?

You get more confident when you know you can move quick enough.

You had a defining moment early in your time with the White Sox.

In 1978, I made two errors against Baltimore in Comiskey Park, and Bob Lemon was my manager. They were easy plays, and I cost us five unearned runs. I was nervous.

After the game, he took me in and put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘look, you’re back out at shortstop tomorrow night.’ It was like, ‘OK, Pryor, you got a chance; you got a reprieve.’

So I went out there the next night, and I started telling myself mentally, ‘Greg, you proved you’re good enough. Just do what you did at AAA.’ I kind of forgot the pain of making the errors and remembered the joy of fielding a ground ball.

From that moment on – when Bob Lemon forgave me for costing us that game — had he not forgiven me, we wouldn’t be talking right now.

That was a potential career-changer.

Yes, it was! It was!

Along the way, if I didn’t have those mature, confident, trusting hands on my shoulder from a number of baseball men who could lift me up when I was in the gutter, I wouldn’t have played in the big leagues.

You were pretty successful with the White Sox, but then were you disappointed with your role, after they had wanted you to be their supersub sort of player?

The only way to get people to respect you is to be on the field – do it on the field. You  can’t do that on the bench. So in 1979, when I played more than 140 games, up toward 500 at-bats, and I was 30 years old, I was thinking that in 1980 I would be an everyday player too. The White Sox had put me in as a possible All-Star Game candidate in 1979; I was hitting more than .300 for the first three months.

can’t do that on the bench. So in 1979, when I played more than 140 games, up toward 500 at-bats, and I was 30 years old, I was thinking that in 1980 I would be an everyday player too. The White Sox had put me in as a possible All-Star Game candidate in 1979; I was hitting more than .300 for the first three months.

In 1980, the White Sox weren’t winning, and teams look at what they can and can’t change. One position they decided to change was to get Todd Cruz to play shortstop, and they wanted me to play third or be a backup infielder. I kind of got disappointed, because Tony La Russa had told me before the season that I was his shortstop. When he changed his mind, you get hurt because like I said, when you’re not on the field you can’t create more value in your game.

I didn’t take it the best way. I was a team player, but in that case I wasn’t, because I was more of a Greg Pryor player at that time.

Then I think the strike of 1981 kind of hurt everybody. I didn’t play that much, and I didn’t have a very good season. Over the winter, the White Sox decided they were going to find someone else to take my job. They traded me to Kansas City, and they got Aurelio Rodriguez from the Tigers to fill my job. And in 1983 they won the division.

So it hurt being traded, in a way, but it was a blessing in disguise, because I got to be around some wonderful All-Stars in Kansas City for five seasons.

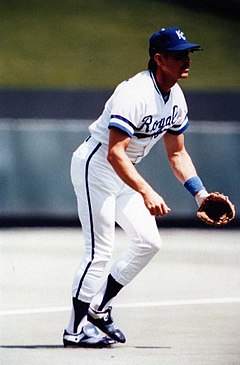

In Kansas City, you had Frank White and George Brett in the infield. Was it easier to accept being a backup there?

When I was with the White Sox, I didn’t like the Royals; I didn’t talk to them if they got on third base. I wanted to beat them.

So when I got traded to them during the last part of spring training, I was shocked initially. Tony La Russa told me I had been traded, and [Royals GM] John Schuerholz is in the next room, and he wants to meet you. I walked in and shook hands with my new boss, and said goodbye to my old boss.

The next day, I had to walk into the Royals’ clubhouse with my White Sox travel bag. I walked into this strange clubhouse, and it was the strangest feeling, being around these guys who I didn’t like. I did learn to like them eventually [laughs].

walked into this strange clubhouse, and it was the strangest feeling, being around these guys who I didn’t like. I did learn to like them eventually [laughs].

George Brett came up to me and said, ‘Greg Pryor! Did we trade for you?’

‘Yeah, last night.’

‘Oh, great! Let me ask you a question: how come you never talked to me when I was on base when you were with Chicago?’

‘George, I didn’t like you one bit.’ He started laughing.

‘Do you like me now?’

I said, ‘I’m gonna try!’

It was wonderful! I learned to love those guys.

You were on Royals teams that won divisions; you were on the 1985 team that won the whole thing. Even though you were a part-time player most of your time there, was the World Series the cherry on top of the sundae for you?

The World Series was my biggest thrill in the game, for a lot of reasons.

But in 1984, we won the division and I played in about 120 games, so my best personal feeling I had in the game was being able to play in place of George Brett and Frank White and we still won our division. I did my job, and I was an important part of all that, along with a bunch of other guys.

You get accepted by your teammates; I became one of the guys. Dan Quisenberry nicknamed me La Machine. He said, ‘you play the game like you’re a machine.’

In 1985 I didn’t play as much, but my greatest feeling as a team player was when our team beat the Cardinals. I wear my World Series ring as much as possible.

I was just lucky that a guy who had to walk on to play college ball ended up on a World Series winner. It’s a thrill that I never stop talking about.

Players can have an effect on a team, even if they’re not playing. When George Brett won his first Gold Glove, he said at the winter baseball banquet that when he was hurt in 1984, he learned more about how to play third base from me, and without that, he would not have won a Gold Glove. That meant a lot to me.

Your teammates gain confidence in you, knowing you can do the job.

My biggest test as a player was in 1984, because I was replacing George, and it was my free-agent year. I was 33 years old. Either you do it, or they will find someone else. It was a big challenge, and when you do it, and you prove you can help the team, guys like Amos Otis, Willie Wilson, Hal McRae — when they accept you, you can feel it.

It’s not always a friendship club – it’s a business – but when you do your job, the other players will accept you because you are good enough to help them win. You get into the fold by doing the job, and not by being a nice guy, let me tell you.

There are plenty of guys who are not nice guys, but who are great ballplayers.

Yes! Talk about Reggie Jackson. He didn’t care whether the players liked him or not. He didn’t care. And that’s okay. There were guys on my team – I won’t name them – but they couldn’t care less if anybody liked them or not. As long as they did the job, that’s what they wanted to do.

A general manger always wants to put the good apples with the good apples. He doesn’t want bad apples on a team, because if you get too many bad apples, it becomes like cancer, and it’s hard to have a winning team.

You played about the same number of games in 1986 as 1985, but the offense wasn’t there, and you got released at the end of spring in 1987.

They kind of told me at the end of 1986 that I wasn’t coming back. After I got released in 1987, I got a call from Tony La Russa. He was with Oakland then, and he wanted me to go to AAA Tacoma; he wanted me back. It made me feel good, because he was the only one who called me.

I was thinking about Tacoma in April. If you haven’t been to Tacoma in April, you’re lucky, because it’s freaking cold there. I was looking at going back and playing in AAA after playing in the big leagues for nine seasons.

I had just had my third daughter, and I was still under contract to the Royals, so I was going to get paid. Tony said, ‘I’ll try to call you up as soon as I can, but I need you to go to Tacoma.’ I talked to my wife about it, and I can’t imagine going back to face AAA pitching at 35 years of age. I just can’t imagine myself doing that.

So I ended up telling Tony that I didn’t have it [in my heart] to go to Tacoma, and I ended up retiring after they released me.

When you review your career and the journey you’ve had, are you okay with it, now that you’ve had some time to reflect?

I don’t look back on it too much, but I do wonder what would have happened if I had gone [to Tacoma] and gotten called up. But I didn’t, and I’m pleased with what happened in my career.

Mother Nature never stops. You’re not getting younger when you play ball. And the only way you can become a good ballplayer is to learn how to play the game inside the lines. And I really didn’t learn how to play until I was somewhat past my prime. The game is so great that it will teach you everything you want to know, if you just let it, you know?

I wish I had learned it sooner, so I could have a better baseball card, but when I do look at my card, I don’t see any embarrassments. I wish I had a higher career batting average, but I can’t complain.

And now you are an author, with your first book coming out soon.

Its 27 stories about my career – unique things that I did. Playing in The Pine Tar Game.  Playing with Bo Jackson. Disco Demolition Night. And more. Tony La Russa wrote the foreword, which is exciting for me.

Playing with Bo Jackson. Disco Demolition Night. And more. Tony La Russa wrote the foreword, which is exciting for me.

The title is based on your decision to grow a mustache, despite the Yankees’ ban on facial hair.

The mustache story is kind of like a springboard for what happened to me – when you get stuck in The System. I got fed up with it. And when you tell George Steinbrenner you’re going to grow a mustache, against the rules, you better have your stuff in order, you know?

For more details and to preorder Greg’s book, check out thedaytheyankeesmademeshave.com.