Jim Kern describes himself as “a one-trick pony who pitched ten years in the major leagues.” But he knew what he was doing, on the mound an off. He enjoyed the game, and played hard. However, he was not consumed by baseball, and in retirement, this avid outdoorsman is happy as can be.

You signed on Labor Day 1967 with Cleveland. Was that after summer ball?

I actually had played junior-varsity baseball as a junior in high school. I could throw the ball hard, but I had very little control. Out of high school, I was probably their second or third pitcher.

the ball hard, but I had very little control. Out of high school, I was probably their second or third pitcher.

Then in American Legion, we had an amazing team that year out of Midland [Michigan], a little town of 25,000. At second base was Terry Collins, who played as high as AAA with the Dodgers, and later was a manager; a righthanded pitcher named Dick Lang, who played for the Angels; another pitcher named Brian Sullivan, who pitched as high as AA in the Cleveland chain. We won the state championship.

I signed for $1,000 as a free agent after that.

The problem was, I could throw I the 90s, but when I was 14 I was 6’4” and 158 pounds, so I never had the muscle mass to really control the length of the lever arm.

You certainly paid your dues in the minors.

Spent four years in A ball; two years in AA; two winters playing in Mexico; and one year in AAA.

But playing in winter ball was a turning point in your career.

Really, things started to come together in the summer of 1972. I was 3-11 with Elmira in AA, and I went to winter ball. Jim Campanis and Dave Augustine recommended me when they needed a pitcher.

I went 8-3 and came back the next year, got assigned to AA in San Antonio. I was 12-7 that year, then in Oklahoma City the next year I was 17-7 with a team that was 10 games under .500. I broke the American Association record for strikeouts with 220 in in 189 innings, and strikeouts in a game with 19 in my last start against Denver.

What was it about winter ball that made the difference for you?

It’s a different scenario when you go play winter ball. In a chain like Cleveland, you have a reputation – after four or five years in the minors, they kind of think they know what you have, and work accordingly.

In winter ball, its balls to the wall. It’s very simple: you produce or you go home. And they want innings, they want games, and they put you in a position where it’s do-or-die.

I really lifted myself in that position. You weren’t coddled at all. By the next year in San Antonio, I just seemed to have more confidence, and I started out well, and got viewed differently.

But there were still bumps in the road for you; you almost quit the game in 1974.

In ’74 they were getting ready to send me back to AA, and I was 24 or 25. I had a wife and a son. And I told them, ‘It’s real simple. I am not going back to AA.’ I had an associate’s degree in biology and chemistry, chemical-engineering major, and I flat told them, ‘I’m not going back to AA; I’m going home.’

So they told me they would give me six weeks in AAA, to see what I would do, and I ended up knocking them dead in AAA that year.

You were 17-7/2.52. But it wasn’t a physical thing, or learning other pitches? It was confidence?

It was more confidence. Sure, I gained some weight, and that helped my control; but I had a manager, Red Davis — an old gentleman who believed in me.

In the middle of the season, the minor-league pitching instructor for Cleveland came into town, and Red pulled me aside and said, ‘listen to him. He’s going to give you suggestions, because he’s going to try to take credit for some of your success.’

He said, ‘take what you can use, and leave the rest. Be congenial. Don’t [irritate him]. But do what you’re doing. Don’t change a damn thing.’ So this was Red Davis’ attitude, and how he treated me.

It helped a lot.

How were you treated differently with Red Davis?

He let me run the way I wanted to run: instead of sprints, I ran foul lines — 25 or so a day — to build up stamina. I had 14 complete games that year in 25 starts, and I had 24 decisions in 25 starts.

It was a matter of people approaching me differently, and giving me the opportunity. I was 6-1 or 7-1 going into June, and that built confidence in the manager, so I got more ability to run my life, and my conditioning, the way I thought I should.

Oklahoma City was a good year. Things went right, and you build confidence down the way. I was simply blowing people away at that point. I did well in the AAA All-Star game, which gave me even more confidence going into the second half of the season.

At the end of 1974, you were called up to the Indians. You got into four games,  with three starts. You sort of got your feet wet in the big leagues.

with three starts. You sort of got your feet wet in the big leagues.

I went to the major leagues and got beat by Mike Cuellar in my debut – my only complete game in the major leagues. Cuellar beat me 1-0. That was the fourth game of five consecutive shutouts that Baltimore had that September.

In 1975, you made the Indians — but as a reliever.

Dennis Eckersley and I made the team together. He was a complete pitcher at age 20.

Then they made the big trade for about five people [Gaylord Perry to Texas for Jim Bibby, Jackie Brown, Rick Waits, and $100,000; June 13, 1975] and they told me they had to send me down, because I had an option left. I was really miffed about that.

I went to Oklahoma City, and I had a poor attitude. They called me back up, and I pitched six innings in Boston. I managed to stretch a ligament in my rotator cuff, so that pretty much trashed the rest of that season.

You got a jump on the 1976 season.

Going into spring training – abbreviated because of a strike—I had gone to California in January, where my in-laws lived, and I had been pitching with a high-school team, throwing batting practice and kind of an assistant coach. So by the time I got to spring training, I had probably thrown 40 innings of BP and squad games for this high-school team, so I was well into the end of April in a normal season.

I wasn’t supposed to make the team, because they thought my arm was trash, but in spring I think I pitched 26 innings and gave up one run. So Frank Robinson took me with the team because I was out of options—if they send me down, they lose me.

I was the tenth man on the pitching staff. I was the mop-up man. I had a very resilient arm. I pitched as many as 8-9 days in a row and I could get ready in the bullpen quickly, so I filled a niche.

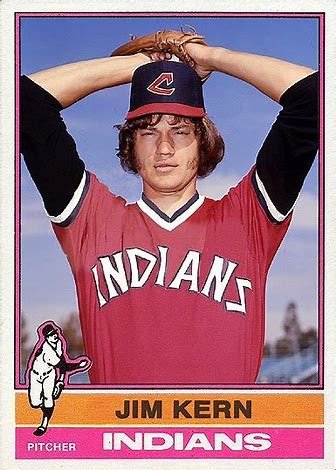

Your role expanded as the season went along.

I started the season in long relief, and I did well. By midseason, I was setup man for Dave LaRoche, who was the short man; and by the end of the season, I was pitching as much short relief as he was.

I ended up 10-7 with 15 saves and a 2.26 ERA, and I had impressed Frank Robinson enough that they traded Dave LaRoche, gave me a three-year contract, and made me short man at that point.

Were you OK with that load? That was pretty much the end of your starting.

After seven years in the minor leagues, any way you can stay in the big leagues is what you’re going to do. It was a situation where I knew I was kind of out of my class, really, in the level of athleticism of the players. I was in the bottom 10 percent of major-league players that way.

So what is your plus? Well, I could throw as hard as anybody.

I became much more successful when I admitted to myself, “you’re a horse***t pitcher. But you’re an awesome thrower.

It was the attitude that “you’re never going to be a good pitcher, but you’re as good a thrower as the world’s ever seen, so go with what you’ve got.

So we kind of developed the “emu attitude.” Fritz Peterson and Pat Dobson gave me  that nickname in Cleveland. They were doing a crossword puzzle. I walked by, and I’m 6’5” and 180 – an emu: the world’s largest nonflying bird.

that nickname in Cleveland. They were doing a crossword puzzle. I walked by, and I’m 6’5” and 180 – an emu: the world’s largest nonflying bird.

And so you stop and think about it: I’m here, and I’m doing well. How do I stay here?

And so your plusses are, you throw the ball hard; you’re inherently wild; so let’s use this to our advantage, instead of fighting yourself on the mound.

So I would stand on the mound and scream at myself. I really wanted the hitters to think I was nuts. Here’s this 6’5” guy who looks like Ichabod Crane, yelling at himself. He throws in the upper 90s, with minimal control, and he doesn’t give a [crap].

Consequently, it got a one-trick pony ten years in the major leagues.

They were never going to give me a chance to be a pitcher Like Frank Tanana, when he hurt his arm and could no longer throw the primo gas. It was a matter of thinking your way through it, instead of fighting to be something they were never going to let you be.

Go with what they will let you be, and do the most you can with it.

A reliever who threw as hard as you did was tough on hitters.

When you had starters throwing sinkers and sliders in the upper 80s for 7-8 innings, and then you brought in this guy who could throw in the upper 90s, the hitters were not able to turn the dial up, once around the batting order. So you had that shock effect, which became very effective.

Is it true that for three years, Frank Robinson wouldn’t let you throw anything except fastballs?

That is correct. It’s interesting when everyone knows what’s coming, and it became ‘see if you can hit it.’ It does make you learn how to drag your arm; throw two-seamers and four-seamers; make the ball move in different situations.

What was your approach, then?

I threw for the middle of the plate, as hard as I could. When things didn’t go well, I didn’t back off; I threw harder. I threw a four-seam fastball and aimed for the middle of the plate, until I got 0-2 or 1-2; then I played with the corners. When I got to 2-2, it was aiming for the middle of the plate again.

I could throw a two-seamer that would sail in to righthanders; I could throw a two-seamer that I could get to sink a little and go away from the righthanders; and then I threw a four-seamer over the top and put enough backspin that it would take off 6-7 feet in front of the plate.

I struck out a whole lot of batters throwing the ball waist-high, and by the time they swung at it, it was chest-high. [Rangers catcher Jim] Sundberg said my fastball gave people the impression that six feet in front of the plate, it accelerated; it just tied people up.

But it wasn’t just power.

Another thing I did was to look at the situation. Everybody in the league was making a living on the outside half of the plate; get them to hit to the big part of the field. My philosophy was, it took milliseconds more to get the bat head around to hit an inside pitch than an outside pitch.

My game is speed and beating you. — On his approach to hitters

My game is speed and beating you. So I have a better chance of beating you — maybe just by milliseconds, but I will still have a better chance — on the inside half of the plate. The hitters were looking outside. So until you hurt me inside, you didn’t see a pitch outside.

Gaylord Perry taught me that you only have one rule when you pitch inside: if you miss, you miss off the plate; don’t miss over the plate.

So I ended up thumping a lot of people.

I think I hit Don Baylor 11 times, and I guarantee, half of them were strikes. He loved the ball away, and he would stand on top of the plate, lean over it, and basically try to intimidate you into throwing the ball away.

But you were not intimidated, and you continued to pitch inside.

I had just spent six years in the Marine Corps Reserve, so the idea of getting into a fight didn’t bother me at all.

My attitude was, ‘come on out to the mound after I hit you. We’ll get this over with, and eventually you’re going to have to get back in the batter’s box — and let’s see who gets tired of this silly-ass game first.’

I made a living on the inside half of the plate, when nobody else did. I had a lot of people afraid of that inside pitch.

My philosophy was that the talent at the major-league level was so close, that If you could get an edge – shatter their confidence by a couple percentage points — you had an edge. And the psychological benefit was me acting crazy.

After the 1978 season, Jim was traded to the Texas Rangers, where he had his best season in 1979. Read all about his 1979 season here.

The Rangers had big problems in the second half of that 1979 season – losing 30 of 40 games at one point. This happened several times to Rangers teams, and it’s been said that perhaps the extreme Texas summer heat was a factor in these second-half fades.

I don’t think the heat had anything to do with it. It’s harder for visitors to come in and play a three-game series in that heat instead of being acclimated to it.

I think a lot of it is psychological. When you’ve had trouble in the past, and then you start to struggle, then you start to look at it. Perception is reality. When you expect bad things to happen, you have a much greater chance they’re going to happen than if you don’t expect it.

[In 1979] we found a way to lose every night. But then, we were really struggling and trying too hard. Everyone was playing outside the envelope and attempting to do more than they should have been doing, so it’s self-defeating. Kind of like a stone rolling downhill, or a snowball that just gets bigger and bigger and bigger. ‘What can happen tonight?’ I think that psychological problem is what kills you more than anything else.

The Yankees believe they’re gonna win. If they’re 20 runs down in the eighth, they still believe they can win. I think that’s what makes them so successful: they expect to be successful.

You suffered a hyperextended elbow spring training 1980.

I threw a pitch, and the bottom half of my arm went numb. I tried to pitch with it for a while.

I tried to adjust my arm slot so it hurt less, and by doing that I managed to impact three vertebrae in my neck. From the years of being tall and skinny, and all the throwing, the muscle definition and even the bones in my right shoulder are considerably larger than my left.

And so what I managed to do is, I overbuilt the right side so much that it was actually pulling the spinal column away from the left side, and locking up vertebrae.

About the end of April, when I extended the left arm and elbow and pulled it through, it felt like it felt like someone was trying to tear the trap [trapezius muscle] off my left shoulder. I tried to pitch with that for about six weeks and flat stunk, and I finally went on the disabled list.

It took me the better part of a year to rebuild the left side to be able to take the beating the right side was giving it.

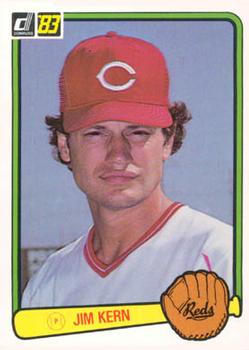

After the 1981 season, you were traded to the Mets, but you never played for them – you went to Cincinnati instead.

I had a great year [in 1981] and [Rangers GM] Eddie Robinson traded me that winter just to make a trade, so I went to New York – was with them for a month and never even talked to their front office. I guarantee they were just prepping for the George Foster trade; getting the people Cincinnati wanted to make that trade, and I was traded to Cincinnati.

The 1982 season was a disaster for Cincinnati – the only time a Reds team lost 100 or more games. It was a mess for you, too.

I had a good year there. I was setup man for Tommy Hume, who was the short man, but I think I pitched 25 consecutive scoreless innings in July and early August, and it was evident – the following year was going to be the last year of a five-year contract, and I told them I wanted to renegotiate.

They said, ‘no way, until after the season,’ and I said ‘fine, I start growing my beard today.’ [The Reds had a strict no-facial-hair policy.] Six weeks later, I got traded to the Chicago White Sox.

You must have felt like you escaped when you got traded from the Reds.

It was just a matter that I was going to put pressure on them: If you want to play your silly game, go ahead – play your silly game.

I had a Nike contract at the time, and so I wore those shoes and made five grand a year, which was big money at that time with Nike. And Cincinnati said ‘No, it’s gotta be black-on-black.’ And it was like, ‘bulls**t!’ I was player rep at the time, and so at that point we started a suit against Cincinnati, which I’m sure helped me get traded, but eventually [Reds executive Dick] Wagner lost.

It was all of that situation.

What a mess – it seemed so dysfunctional.

Big time. Big time.

How was your time in Chicago?

Hell, I even started there. I got into the seventh inning as a starter in September for Tony La Russa.

I went to spring training the next year, and I was having a lot of elbow trouble – where the tendons attach inside your elbow. Their doctor shot me up with cortisone and said, ‘go ahead and throw – you can’t hurt it.’ Well, I tore the flexors and the pronators completely off the elbow. They had to go in and operate, and put everything back together. Then they released me without even looking at me, when I was still rehabbing.

From that point on, it was the mercenary state of my career – I was modeling uniforms. And I looked good in all of them, man [laughs].

Did you have to change your motion?

After I destroyed the elbow, it was very simple:

I had eight years and 156 days of big-league time. Ten years was maximum pension benefits. So I needed a year and 16 days on a big-league roster to hit maximum pension.

What I would do is, I would pitch all winter, go to spring training with someone on a minor-league contract, and when I hit spring training, I was as good as I was going to get after pitching all winter. The hitters hadn’t done a damn thing all winter, so I looked good against them n spring training.

Then when the kids got up to speed about the first of May, I wasn’t getting any better, and they caught me and they hammered me. And I would get released in June.

OK, now I have, let’s say, nine years and 30 days; I need 137 days. So, the same scenario. I would pitch all winter, go to a team on a minor-league contract in the spring, and make the team. About the middle of June, I got released.

OK, now maybe I need another 27 days. So I did the same scenario, made the Cleveland team, worked my ass off, gave them their money’s worth, but the kids caught up to me by June, and I retired with 10 years and five days of major-league time.

And that was it?

They offered me a minor-league coaching job when they released me, I’m sure that was to recover some of the salary they were paying me – but by the same token, my love in life was hunting and fishing, not baseball. I enjoyed playing baseball, but to go back into the minor leagues and be a coach, and hope somebody you played for got a major-league job, and riding buses – that wasn’t gonna happen.

Hunting and fishing, and the outdoors — that’s how you have made your living since you left baseball.

The last 32 years. I started a company in 1987 called Emu Outfitting. We started renting Texas hunting licenses here. Only 1 percent of Texas land is public, so if you want to hunt, you lease hunting rights on a ranch.

What I would do is go and lease the hunting rights on a 50,000-acre ranch, say for $4 an acre. Then I would split it up into 5,000- or 10,000-acre sections, then release it to groups of hunters for 6-7-8 dollars an acre, and that’s how I made my money.

Then we started running guided hunts in Idaho and Montana, and then I started booking peacock bass fishing trips in the Amazon. I managed hunting and fishing lodges in Alaska for 6-8 years, where we would have a staff of 15 people and run 12-20 guests a week, fishing from mid-June until end of September. From the end of September until the end of October, I would guide brown-bear hunts, moose hunts, and caribou hunts.

I’m doing what I love: the outdoors. My wife used to accuse me of playing baseball simply to facilitate my hunting and fishing.

My earliest memory, when I was about three years old, is of my father putting me on his shoulders, carrying me out on the artificial piers in Lake Michigan, tying me to the pier, and fishing all day — then carrying me back at night.

Are you still running Emu Outfitting now?

Yes. We do some Alaska bookings, but mostly we do peacock bass fishing in the  Amazon. I have been to the Amazon 35 times.

Amazon. I have been to the Amazon 35 times.

[For more information, check out peacock–bass-fishing.com or emuoutfitting.com.]

Are you satisfied with your baseball career?

I actually felt bad when I was in the minor leagues, because my goal never was to play major-league baseball; I originally signed a contract because it put me through a year of junior college.

When you had these kids who were getting released, and their whole life was oriented around making the major leagues, their whole life ended. And I felt guilty because I was still there, and that wasn’t my dream.

It’s like a high-school baseball team with money. — On playing in the big leagues

Things worked out; playing major-league baseball is a thrill and a lifestyle that you just can’t describe. Unbelievable. I tell people it’s like a high-school baseball team with money. So that part of your life is something you wouldn’t trade.

But I wouldn’t trade my experience in Parris Island Marine Corps boot camp, either. Not that you wanted to do it again, but it was an awesome experience.

You are a true outdoorsman.

Hunting and fishing, I just love going where no man has ever been before. In the middle of the Amazon; Alaska, 180 air miles from the nearest road; fishing in close proximity to 1,000-pound brown bears; guiding people where you have three or four brown bears within 50 yards, who are fishing with you. Flying, looking at the volcanoes, the glaciers – unbelievable.

My Lord, the life has been awesome! — Jim Kern

No, I didn’t make the money they make today – I made $325,000 one year after being a three-time All-star – but my Lord, the life has been awesome!

I just enjoy life, and every facet of it.

As long as you are able?

Oh yeah. I have five stents in my heart, and my idea of a perfect way to die is to be fly-fishing and fall over into the stream, dead. Go as hard as you can, as long as you can.

That’s good advice for pitchers and outdoorsmen, isn’t it?

Absolutely!