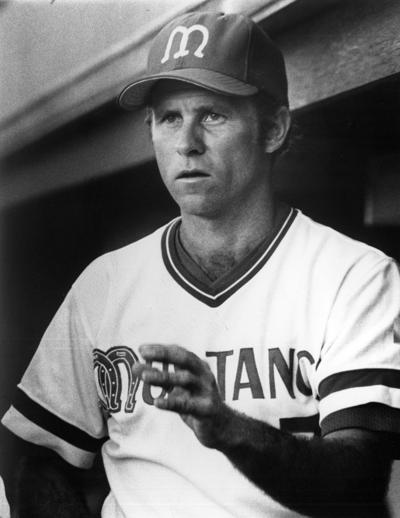

Marlon Styles receives a throw as Boise’s Mike Hunter scores on a sacrifice fly, August 28, 1975

Cincinnati native Marlon Styles Sr. was a fifth-round draft pick of the Reds in June 1973 (Aiken HS). He played four seasons in the minors (1973-1976), and was the starting catcher for the 1975 Eugene Emeralds Northwest-League-winning team.

Marlon Styles Greg Riddoch told me that you’re putting this together in book form for him, and you had contacted a bunch of the teammates to get testimony from them.

Jim Haught [laughs] Testimony! That’s pretty good. They didn’t admit to any crimes, but they gave testimony!

MS All lies, or – [laughs]

JH Everyone keeps saying, you’ve got to talk to Marlon! You got to — he’s got to talk to you, because he was so important to our team, and such a good guy and all that.

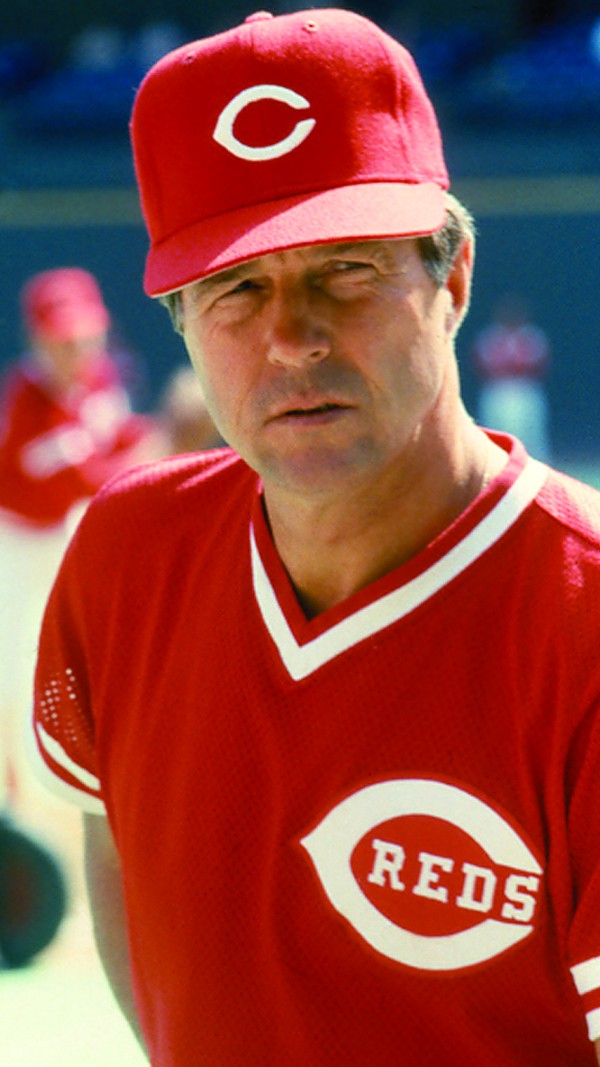

I think that there was another piece of glue on that team: our catcher, Marlon Styles –– Emeralds pitcher Paul Moskau

MS Well, I mean, it’s the best time I had in the minor leagues. Just to put that out there right away.

I was in the minor leagues for three-and-a-half years. I was drafted in 1973, and going to Eugene, I knew nothing about it other than they had zero crime in 1975. There was no crime in Eugene. And that’s what stuck out to me when they told me I was going there.

And I had a bad accident on my way there. So I had to leave my car in Florida, and my father came and got my car and drove it home. So getting there, it was kind of a — what’s the word? emergency. Because the Reds were mad at me because I had gotten this car, and they felt that I needed glasses.

So the year before that, I was in Tampa, and there’s a pitcher that had never thrown to a Black catcher before. So that night, I caught him, and I mean, I must have had six passed balls. And they booed me and booed me and booed me! And you know, it was not good.

So the next spring training, they told me that I needed to make sure I got these glasses, but instead of getting the glasses, I bought this car. [laughter]

JH A man’s gotta have priorities!

MS So on my way driving to Eugene, I wrecked my car, and Chief Bender told me that he didn’t care nothing about that car; I better get my butt to Eugene. And so that’s how I started my travels to Eugene. And didn’t know anybody, other than Tommy Watkins. [Watkins story here]

JH Because he’s another Florida guy, right?

MS Yes, yes. And some of those guys stayed in the same hotel during spring training that I knew, but getting to Eugene, I didn’t know Skip Riddoch, either. I didn’t know him. I knew of him, but I didn’t know him personally.

JH Word had gotten around already about him?

MS Yes, that he was a really good man. And I knew Mario Soto, because we were drafted the same year.

JH 1973. That was right out of high school for you, right?

MS Yes, yes. And so when we get to spring training, when we get to extended-spring, the manager, his name was Ron Plaza –

JH Uh-oh!

MS And Ron, we called him The Dragon! Because he came out to introduce himself to us, and he was in a pair of cutoff shorts, cutoff T-shirt. He’s got flip-flops on — shower shoes — and he’s got a cigarette in his hand. And so he takes a huge draw of the cigarette, and he starts talking. He looked like he was a dragon: all this smoke was coming out of his face. And I’m an 18-year-old kid, you know. I feared my father, and now I’m scared of this guy.

JH He kind of liked to instill fear in people, from what I understand.

MS Yes. And he was a very intimidating man.

JH That was part of his M.O.

MS Yes. [phone rings] This is my scouting director. Let me call you right back.

[Marlon takes the call, letting him know he has been furloughed as a Cincinnati scout, after more than 20 years. It ended with a phone call.]

Several minutes later …

MS They furloughed a bunch of us today. So this [2020] was to be my last year scouting. I’ve been scouting for the Reds for 23 years now, and all on a part-time basis. I never wanted or could be away from my kids or grandkids for a long period of time, so I never went full-time. But as all sports are doing, they’re just chopping heads now to make up some of this revenue that’s lost.

JH It seems like there’d be better places they could do it then do it with scouts, but that’s just one man’s opinion.

MS Right. And you know, there’s nothing to scout right now. So with everything being shut down — we’ve been shut down since the beginning of March when [Ohio governor Mike DeWine] said, here’s what we’re going to do. So we got the call the second week of March that we were shut down completely. But there’s nothing to scout, so everybody’s running for the hills now.

JH That’s a sad way to have to go out, isn’t it?

MS Yeah, I know. That’s what my scouting director was saying right now. He said he just wanted to call, and me and him are really, really, really good friends. I respect the hell out of him, and he’s been good to me and my family and — as the organization has for these last years. So it was just kind for him to personally call.

JH I’ve heard of guys having this done — being let go — by email and stuff like that, and just kind of get kicked to the curb, and it’s nice to at least get it in person.

MS Yeah, they called everybody personally.

JH At least, especially somebody with your amount of service time — you’ve given a lot to that organization.

MS Yeah. They’ve been — and I worked for three owners. I worked for Mrs. Schott and Mr. Lindner, and now Mr. Castellini, and it’s been a great, great run, in regard to how they treated me and my family.

JH At least you have that.

MS Yes, yes, yes.

GETTING STARTED

JH Let’s go back to the beginning and work our way back up to Ron Plaza and the rest of those guys. Kind of get a thumbnail of what got you to the point where you were dealing with Puff the Magic Dragon there.

How did you develop as a catcher? Were you always a catcher?

MS Yes. I was heavy when I was a kid. And so back then, the fat guy was the catcher. [laughter] And so I always caught, and never played anything else. Even in Little League, everything. And I got better and better and better and got skinnier and skinnier and skinnier. You know, I was 5’11”, 155 pounds out of high school.

JH You just got rid of the baby fat, then?

MS Yeah, I was really thin. Plus, I was a multisport athlete; I played basketball, football, baseball.

JH What did you play in football and basketball? Probably a guard in basketball — ?

MS I was a guard on the basketball team. Then I was quarterback on the football team.

JH Wow! Not a tall guy for a quarterback, though.

MS No!

JH Were you an option, Veer kind of guy, or –

MS No, it was strictly dropback.

JH Because you had the good arm?

MS Yeah, I threw really well.

JH Were you born with that? Did you develop that?

MS I think it was because growing up in the inner city, all we did was play baseball; that’s all we did. And all we did was throw: bottles, rocks, rubber balls. It didn’t matter what it was, we were constantly throwing something. And I truly believe that helped my arm strength.

Where I lived, the elementary school we went to had a 50-yard dash on the playground. And the talk of the town was, if you could throw the ball 50 yards, then you were superior [laughs] in regard to your peers — the little guys that we ran around with. So next thing you know, I’m probably throwing that thing 70 yards. And it got better and better and better, in regard to my arm strength.

JH But was baseball always your number-one, or did your size —

MS It was always my number-one. But some people thought maybe football was better. I had a really good sophomore year. My junior, senior year, it wasn’t too good. But baseball was always my first love; always. Because I grew up around Crosley Field. I grew up probably three minutes from Crosley Field.

JH You weren’t part of the bunch who “protected” cars down there, and all that kind of stuff, were you?

MS Yes, that was me. [laughter]

At Crosley Field in the late 1960s, it was a bit dangerous to park and walk to the games; it was a bad neighborhood. The neighborhood kids extorted money from people by offering to “protect” cars from damage, in exchange for a couple bucks. The smart person took no chances and paid up. It was one reason why the 1970 move to Riverfront Stadium was welcomed, despite the charms of the Crosley Field itself.

JH Might have paid you a time or two! I can remember that as a kid, in junior high and high school!

MS That was me! [more laughter]

JH Going down there and being offered certain services in exchange for a couple of bucks — and we were happy to pay!

MS Yes. I started parking cars when I was eight years old. And then we parked cars and then we’d catch Peanut Jim [Shelton, a legendary vendor at Crosley Field] coming down the boulevard, and then we’d go right behind the left-field screen and catch all the home-run balls that were hit during BP. And then we’d go into the trailer where the clubhouse was, cause you could just walk in there and go sit right next to Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, and shoot the crap with them. And they gave us all their cracked bats and their broken gloves and you know, we’d use them come Saturday when we played our Knothole games.

JH Nice! You weren’t hurting for equipment, at least!

MS No, never. And we always had money, so we could always buy a rubber ball. I mean, we were Sandlot before Sandlot.

JH I hear ya! Playing stoop ball and stick ball and 500, and three-flies/six grounders and all those kinds of games like that, when — as long as you can get three or four people up, you can get something going.

MS Right! We went neighborhood-to-neighborhood and street-to-street, and it was great.

Marlon got a rude awakening to baseball reality when the 1973 draft choices assembled in Florida.

MS So Plaza tells us that there were 31 people in the draft. All 31 of us were there. And he thanked us for getting there safely. And then he said, none of you will make it to the big leagues. Then he said, maybe one, and that won’t be with us. That was this opening statement. [laughs]

JH Thanks, man! A motivational speaker.

MS And so, I mean, he was right. Mario Soto was only the person that made it to the big leagues out of that draft. He was the only one to make it to the big leagues.

And I got promoted that year to Tampa. And that’s when I ran into trouble, with them thinking that my eyes were bad. And so they got me glasses, and then I went to extended-spring and I did really well there. Sparky Anderson was the Reds manager then, and he fell in love with what I was doing. And so the next spring training, my first spring training, they sent me to AAA; I worked with the AAA team. So then, after everybody got filtered down from the big-league team, I went down to the single-A level. And that’s when they sent me to Eugene.

JH Yeah, because you’re talking about — are you talking about 1974 here?

MS This is 1974.

JH Because you had a few games with Seattle, it looks like. And then —

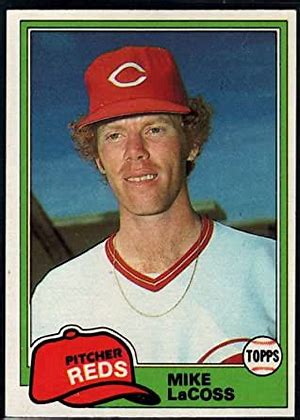

MS Well, I went to Billings first. And then I went from Billings to Seattle. When I got to Seattle,  they had three pitchers, Mike LaCoss and two other guys who — I don’t get their names right off the bat — the catchers that they drafted couldn’t handle them.

they had three pitchers, Mike LaCoss and two other guys who — I don’t get their names right off the bat — the catchers that they drafted couldn’t handle them.

So Ron Plaza came to me and he says, Hey, we got a proposition. It’s up to you whether you want to do it or not. We’re not saying that you have to do this, but we’re in a bind. These guys are really good, and we don’t have anybody that can handle them. So would you be willing to go back down to rookie ball? And I thought about it and thought about it and I told him, you know, if that’s what you want me to do, I’ll do it. So I did it.

And I regret it, you know? To this day, I regret it. I think if I would’ve just stayed on the path, it might’ve worked out a little better. But I had to go backward in order to go forward again, in order for them to — and they appreciated it; they did. They were very appreciative of that, actually.

JH But it didn’t help your career.

MS No, it did not.

JH I mean, when you just look at it here on Baseball-Reference and you see up and down, up and down, up and down. Now, I understand being a catcher in the Reds organization had to be pretty tough in those days. But still you’re in Tampa in 1973 and you’re in Tampa in 1976, and a bunch of bounces-around in between. It’s hard to say you got a fair shot anywhere, really.

MS And me not getting those glasses really, really hurt. If I had it to do over again, I’d have just gone and gotten the glasses — forego the car.

JH You couldn’t drive the car anyway. What kind of vision problem was it? Was it a depth-perception thing, or — ?

MS No, when they checked my eyes they were fine, but they didn’t want to hear that the guy just — the guy couldn’t see my fingers. And so I’m putting down a fastball and he’s throwing a breaking ball. Put down a breaking ball, he’s throwing a fastball.

Russ Nixon was our manager, and he was extremely mad at me, because he had heard so much about me while they were promoting me up to his team from Bradenton. We were down in Bradenton, Florida, then.

JH Is that what accounts for — in 1974 there were 33 passed balls?

MS And I was in a game where I went to bunt, and I slid my left hand up the bat and the ball hit me right on my middle finger and busted it wide open. I had three stitches put in that finger. And so while it was healing, I continued to play. And so every time I went to catch the ball, I would tilt my glove back, so the ball would hit at the top of the glove instead of hitting in the pocket. It was painful to do that.

And Jim Hoff was our manager then, and he came out, he called time-out. He came and stuck his face in my face: Are you trying to passed-ball me to death, or what?

JH You were trying to make sure you caught it in the webbing and not in the pocket?

MS And not in the pocket, because it hurt every time I caught that ball in the pocket. But it didn’t help, because they thought for sure that my eyes were bad. But when I left Seattle and went back to Billings, and I went to Eugene, everything was fine in regard to the guys that we had there.

JH Yeah. I mean, they could see your fingers and all that. So you didn’t have to resort to —

MS I started painting my fingernails.

JH I was going to say, you didn’t have to resort to taping your fingers.

MS Yes, we used tape. But then it was such a hassle getting it off when you hit that I said, okay, well … and then we started putting fingernail polish on it. And that helped a lot.

JH So you were stylin’ a little on the way to the plate, right? [laughter] I mean, you gotta do what you gotta do, I guess.

MS Yeah. I mean, it was what it was. And so they thought that — because I did really well in the daytime, but then when I got promoted to Tampa, all they had was night games. In Bradenton, all the games were daytime games. That’s what they equated it to: He just can’t see. So they made me go get my eyes checked and then they got me some glasses, and the rest is history.

JH It’s one thing when you can’t see, but if they can’t see you, that’s a little tough. Thinking you’re getting a slider and you get a fastball. That’s just not my idea of a day at the beach.

MS I mean, Jim, these balls were flying by me. I was chasing — every time I turned around, I was at the backstop. That’s the first time I’ve ever been booed, too. They booed the holy hell out of me. Russ Nixon was screaming at me, and it wasn’t good at all. I ended up throwing my bat up in the stands.

JH Seriously?

MS Ron Plaza ended up being the minor-league coordinator, and he was at our game this particular night. And when I got up, when I got to the dugout, Russ was saying some things to me, and this umpire started screaming, we need a hitter up here! So I threw off my gear, grabbed a bat, ran up there, got punched out [strikeout]. And as I’m coming back to the dugout, I mean, I’m just, I’m done. You know, it’s just not going good. And as I’m throwing the bat to slide it on the ground, it hung up on my two fingers and went up in the stands.

I mean, people are ducking, and our minor-league coordinator’s there.

JH Yeah, that’s a good look, isn’t it? That’d be just the kind of thing that Ron Plaza would really be amused by, too. [laughter]

MS Yeah. I mean, it was a roller coaster, to say the least.

JH How did you survive the bat going in the stands?

MS I just apologized, because you know, there were kids running for their lives, and parents.

JH Yeah, that thing goes helicoptering up in there, and … See, now they would have had a net up there, and you’d have been saved by that.

MS Yeah, I’d have been OK. [laughter]

JH But you used the word rollercoaster. Is that kind of a summary for your 3-1/2 years?

MS I would call it that. Probably the best year I had was that 1975 season at Eugene.

JH Can you put your finger on what happened? I mean, I see they had you playing second, third, short, even a game in the outfield, in addition to catching. Did they just not know what to do, or — ?

MS When they drafted me, they told me that if it didn’t work out behind the plate, they would put me out in the outfield, because I threw really, really well. That was probably — receiving and throwing was my strong suit. Probably the best tools I had were defense and my arm strength. So I never hit in high school; I never hit in the minor-leagues, either. But that’s what they told me.

The one spring training, when I came there without the glasses, Chief Bender was — oh, he was so upset with me. And so Jim Hoff was our manager in Billings, and me and Hoffy were really, really good friends. And he came up to me and pulled me to the side. He said, I don’t care what you have to do, but you need to go get some glasses. And if you don’t – because they were — when they saw that car, he was mad; he was so mad.

And so I left there, left after the practice was over, went and got some glasses, and kind of calmed things down a little bit.

But only a little bit. A storm was brewing:

MS I was making $550 a month when they signed me. And then after the second year, the contract was for the same amount of money. So I told my Dad, Hey, they’re offering me the same money; not giving me a raise. He said, well, don’t sign it. Just tell them — write on the bottom of it, NOT ACCEPTABLE. So I did. And Chief Bender calls me and he says, I need you to come down to the [Riverfront] Stadium right now!

JH Uh-oh.

MS So I drive down there, walked into his office. He slammed the door and he says, WHO IN THE FUCK DO YOU THINK YOU ARE, WRITING ON MY CONTRACT? and you ain’t this and you ain’t that!

And you know, I didn’t know the protocol. All I had to do is just maybe put a letter in there along with the contract. You’re never supposed to write on a contract. And he was so mad at me. So he told me, he said, you better have those glasses when you get to spring training, too! That’s what he told me. And I didn’t get ’em.

JH Man!

MS Yeah. I mean, it was my fault; it wasn’t his. He was only acting on what I had presented to them: that I was struggling behind there at nighttime.

JH Yeah, but you weren’t the one who was struggling.

MS It really didn’t matter.

JH No, no. I guess you’re doing this for appearances’ sake. Maybe it’d be better-looking in hindsight, if you had gone to Walmart and got a pair of cheaters and just threw them on – really. Well, I got some glasses, and they still can’t see me! There’s a difference between one, two, and three [fingers] and —

MS Yeah! I mean, it was my fault. I don’t put it on Chief or anything; he was just reacting on what I had presented to him in regard to my struggles, so he had to — because I was doing okay in their minds; I was catching really well. I was struggling at the plate, but I was catching really well. But it just — through my own actions, it became a problem for me.

JH How difficult was it for you to play in Florida in those days, as African American player?

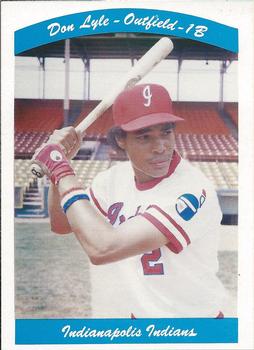

MS It was okay, because everywhere I went, there were older guys with me. When I got to Tampa that same year, there were a lot of college guys on the team: Donnie Lyle and Bobby Jones and all those guys. And so I got in really good with those guys, and kind of followed them around, so to speak.

When I first got to Tampa, Russ Nixon shakes my hand and he says, I got two rules: if you catch the clap, you don’t play. [laughter] And if you don’t play, you don’t get paid. That’s what he said. [more laughter]

JH Those are words to live by!

MS Jim, I don’t know what he’s talking about; I don’t know what the clap is. So I’m sitting there, I  couldn’t play that night. And I’m sitting there in my street clothes, and Donnie Lyle came and sat next to me. Hey, man, what’s this clap stuff? And he got to laughing. He said, you’ll see when the game’s over with.

couldn’t play that night. And I’m sitting there in my street clothes, and Donnie Lyle came and sat next to me. Hey, man, what’s this clap stuff? And he got to laughing. He said, you’ll see when the game’s over with.

So when you came out of the dugout, you made a hard left. And then they had this fence that was separating the field from the parking lot. And then you went into the clubhouse, underneath the stands. And all these girls were hanging on the fence. And so Donnie said, there it is, right there. That’s how naive I was. [more laughter]

JH Jeez, you’re 18, 19 years old; nowadays somebody who’s 19 could probably give you a real lay of the land on that, but it was a little different time 40-some years ago!

MS Yeah, but I mean, it was not a big problem because we didn’t have a car, and where we stayed, what was the name of it? Jungle Pride. That was the name of it. And all the stores are right around the corner from there, so you can walk right to there. And then the Waffle House was there. That’s where we ate every day. And you know, it wasn’t a problem for us venturing out.

JH You didn’t have to be super-conscious of where you were going and when, and those kinds of dumbass things?

MS No, no, because we had curfew anyway, so you couldn’t be out past 10 o’clock. So it just was something that never presented itself to us in regard to us venturing out in an area that might’ve been a little tough for us to be in.

JH I’m glad to hear that you didn’t have too hard of a time there. But it’s awfully hard for me to even envision being in your shoes as an African American player during those years.

MS It was more of a concern for my parents than it was for me, because I had never experienced it, other than — when we were kids, the [Cincinnati] police were really, really, really mean to us. You know, they beat us and spit on us, and the police were just God-awful there in the Sixties.

But other than that, all the people were pretty cool, because my father worked for the railroad and then he got a job working for the post office. And so once he got this job, then he got better pay. And then we moved into this — it was the first gated community, called Park Town — and it’s downtown in the West End of Cincinnati. And so that’s where the mayor lived, and all these affluent people lived there. And so we were around nothing but well-to-do people, all of a sudden. It was a struggle, because our friends didn’t look at us very well. They hated us because they thought that we thought that we were better than them. And that wasn’t the case.

It was more tough dealing with your own race sometimes than it was dealing with the white people.

JH What a screwed-up world this is!

MS Oh, my goodness, Jim! Yeah!

JH Because it’s just shameful to me, and it’s embarrassing. And there is so much prejudice and so much hatred and so much stupidity, and I just really, really struggle with that.

How in the hell did we get in this situation? How did this happen?

MS My father said that once President Obama was elected, we would go to a time to where man had to be really concerned about himself in regards to how he went out into the world. Because there were angry people, but he said, now – he called them extremely angry people.

And he told me – because I’m the only son – you can’t get into any trouble. You can’t get into any fights. You have to remove yourself from any type of racial tension. Because if something happens to you — and I’m probably 12 years old at this time — if something happens to you, my name stops. And that’s all he said. So you’re gonna have to really think about what you do and who you do it with, because you’re the only son.

And he said, I want you to always understand: you need white people. That’s how we were raised. And if they said it once, they said it 2,000 times: Don’t you ever let anybody tell you that you don’t need white people. Make friends with them. Go over to their houses. Have them over to your houses.

Our parents had such a diverse mind that they knew how this world functioned. And how to stay out of harm’s way. That’s one thing that me and my sisters are really proud about: how we were raised.

JH Well, you should be!

MS I was in this grocery store in Alexandria, Kentucky [a suburb of Cincinnati]. I’m at the Meijer’s, and I’m delivering there, and this young man – he was in high school – and he had a learning disability. After school, he would take the garbage out, and all that stuff.

So he comes past me one day, and I go, hey, brother, how you doing? And he looks at me, and he just walks on past. So the next time I saw him, same situation. I said, Hey, brother, how you doing? And he turns around and he looks at me, and he smiles and says, Good, brother. How are you?

And so the next time I saw him, he was at the checkout bagging groceries. I’m in his line, where he’s bagging – ready to bag my groceries. And I said, hey, brother! How you doing? And he said, Good, brother. How are you?

So the next day, I saw him in back of the store. I spoke to him, and he walked right past me. Didn’t say a word. Didn’t even look at me. He had his head down.

JH [angry] Whoa!

MS So the next day I saw him again, and I stopped him. I said, You OK? And he says, No, I can’t talk to you anymore. And I said, OK. Is it something you want to talk about? And he says, I got in trouble for talking to you.

Well, come to find out, the cashier was his Mom. And so when she saw him speak to me, when he got home that day, she unloaded on him. And he came clean about everything. He said, you know, we don’t say kind things about your people at my house. That’s how he put it.

And so I said, OK. We can handle this two different ways: We can not speak to each other, or we can only acknowledge each other when we’re back here in the back of the store. It’s your choice, how you want to play it. And however you choose, I have no ill feelings toward you. I just want you to know that.

So he said, OK. And he walked away.

So the next day, he spoke to me, and he said he would like to just speak in back of the store, where nobody could see us. And so for the first time in his life, he had come in contact with such a person that his parents had been telling him were really bad people – that he realized that wasn’t true.

And so he made a choice that, I want to talk to you, but I don’t want to do it, because I can get in trouble. And so that’s how we maintained our relationship: we just spoke to each other in the back of the store. If I saw him out in the grocery store, or in the aisle, bagging, or putting up stock, I just walked right past him, and I wouldn’t say anything to him. But that’s the conditions that he was being raised under.

JH That’s a shame.

MS I know.

MS My wife’s uncle Bob is 94 years old. And so he was a Marine in 1942, when the Marines were segregated. So if there’s anything that still upsets him, it’s that he never got a chance to fight; Black people weren’t allowed to fight. And so when he hears or sees a person being honored, it really bothers him to this day that he didn’t get the chance to be as such. He said, maybe if I’d fought, I might have died, like a lot of people did. But it just bothered him that he never got a chance to fight, because the military was segregated.

JH Because it wasn’t until, what? 1946 that they desegregated the services.

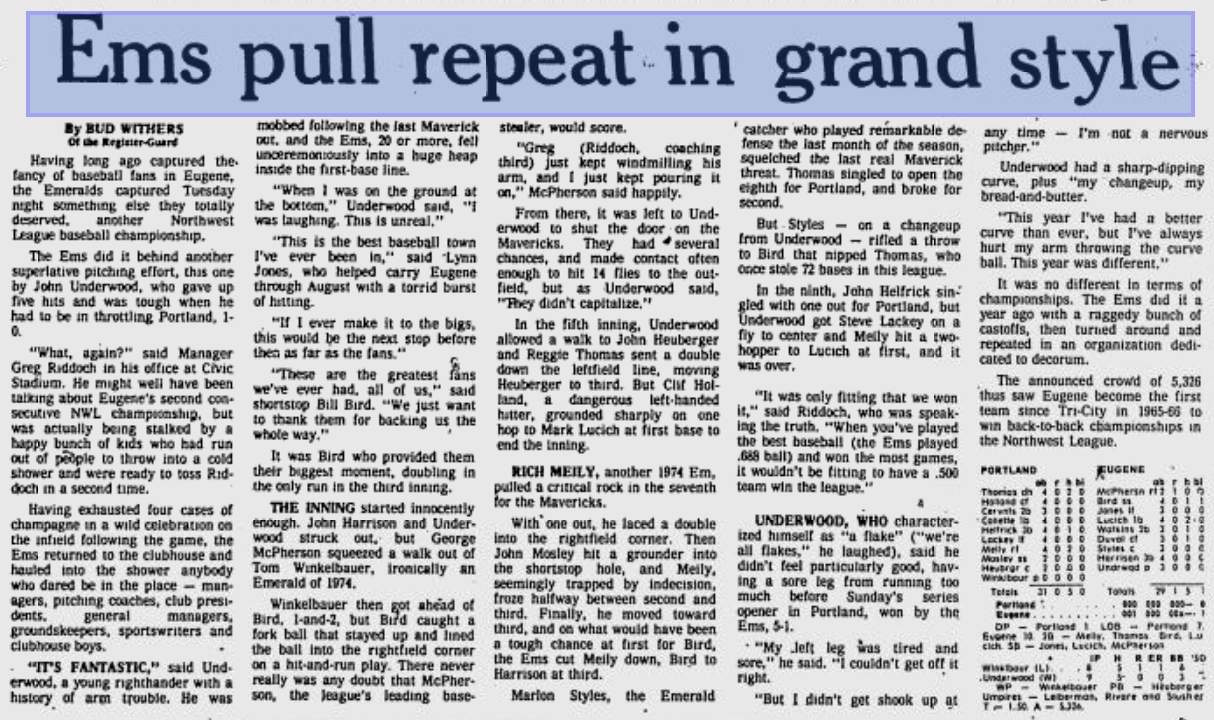

1975: The Little Red Wagon wins the Northwest League championship

JH Let’s talk about 1975 and Greg Riddoch, and the Eugene team.

After a slow start, you guys just catch fire, and go something like 38-8 at one point during the season. And the team was so close; they’re still having all these reunions. You have a manager everyone thinks the world of. What are your memories of 1975? How does that all fit together for you?

MS I finally was on a team where it didn’t matter if I hit or not. That was the first thing that I was excited about: that we had so many good hitters on that team that it didn’t matter if I hit or not. It mattered when they had the Quarter Beer Night, when whichever hitter they called, when he gets up, if this guy gets a hit, all beers are a quarter.

JH A little pressure there!

MS I’d strike out, and they’d boo me! [laughter]

JH Did Greg tell you not to worry about your offense? That you were his catcher, and go on from there?

MS That’s what he told me. It didn’t matter. He said, you’re my guy, no matter what. And I had proved myself back there, to that regard.

And me and Mario Soto were really, really close. And then Mario hurt his arm. Because he was a fastball-slider guy at the time.

JH He didn’t have that changeup yet. Right?

MS No, no. And when he tore his elbow up, they sent him back to Cincinnati, rehabbed him, then sent him back to us. And Ron Plaza and Greg Riddoch called me into the office. And so I come in there and Ron says, Marlon, have a seat. He says, you know, sometimes, I could be in Florida. There’s some times I could be in California. There’s some times, I could be in Texas. And I’m looking at him like, what the hell are you talking about?

So I look over at Greg, and Greg’s got this smirk on his face. I look back at Ron, and Ron says, so if I’m at any of those places, and I hear that you let Mario Soto throw a slider, before you throw the ball back to him, you’ll be on a plane going home.

JH The Reds were big on “no sliders” in those days, weren’t they?

MS So I said, okay.

So Mario comes back, and he still wants to throw the slider. I told him, I can’t let you throw the slider. And me and him are having this discussion out on the mound one night, and he’s going, Goddamn it, Marlon! You won’t let me throw the slider! I said, I’m not going home for your fucking ass! [JH laughs hysterically] You got to throw this changeup!

And so the umpire comes out, and he says, are you guys done? I said, no, we’re not done. I said, I’m not going home for you. And he says, I want to throw the slider. You can’t throw the slider. You got to throw this changeup! And so, as they say, the rest is history.

JH Slider? It makes my elbow hurt, just thinking about it.

MS Yeah. And me and Mario, we were roommates then.

JH How were the roommates getting along that night? [laughter]

But it had to do a lot for your confidence and let you relax, when Greg could tell you, look, you’re my guy, don’t sweat it. Just go through there.

MS Right.

JH But actually, in 1975, you had your best year for home runs and RBI, and all that. Four home runs and 35 RBI in 54 games for Eugene, and hitting .270. So —

MS It was my best year. Yeah. I mean, Greg kept us so relaxed, and we had a bunch of clowns on the team. Billy Bird was a clown, and Mickey Duval was – he was a clown. Lynn Jones was kind of a soft leader, but boy, could he hit!

JH What do you mean when you say “a soft leader”? Is that a guy who leads by example?

MS Example. And he just did his thing and he kept you upbeat, and then I kind of fed off of him in regard to, you know, keeping us looser. Cause I was more of a clown than anything, that I liked to have fun and have everybody laughing.

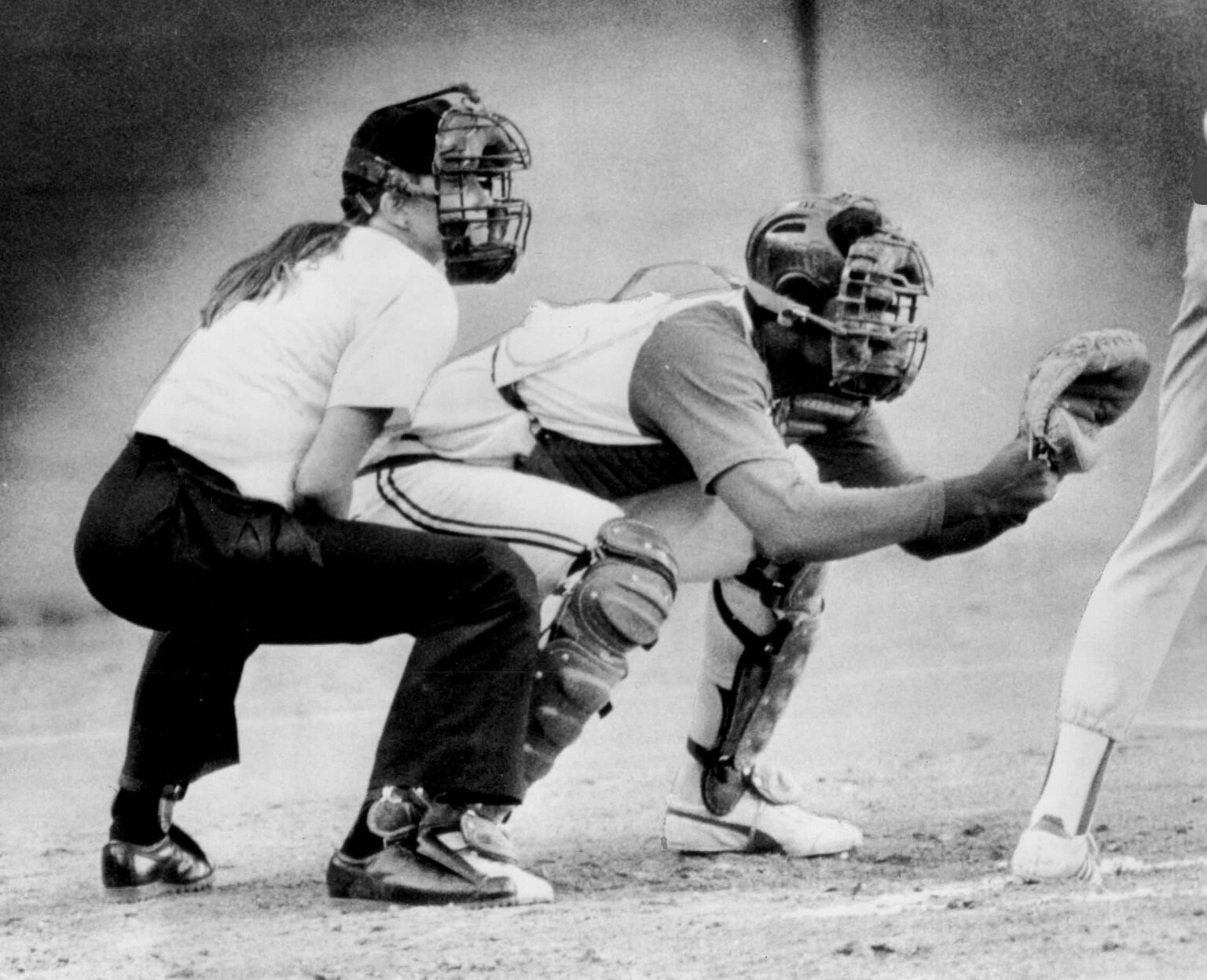

And then, when we had the woman umpire, that got tough –

JH Christine Wren? I have heard, Marlon, from a couple of your teammates. They said, Marlon had it real bad for Christine Wren!

MS I had it baaaad! [laughter]

JH How do you catch, when she’s behind the plate?

MS One night I’m sitting there, and Greg would call — periodically, he would call 0-2 pitches. And so I was sitting there, I’m like, man, I kind of got a clue what I want to throw. Let me check with him.

So I turned and looked at him, and he’s got both of his middle fingers up, giving me the finger! I just started laughing so hard, I fell over, and my helmet and my face mask hit the ground. And I’m bent over, and I’m laughing so hard.

And so Christine, she goes, is he always a dick like that? I said, no, no, no, no. He’s just – it’s just a running joke that he and I have, in regard to this 0-2 pitch. And so the next two pitches, I looked over at him again; he flips me off again.

JH You know, he told me that story, but he didn’t quite embellish it the way you did. I got a lot more detail out of this story now. [more laughter] He did mention that you fell over, though.

But pretty much, you called your own stuff then?

MS Yes, he let me call the whole game.

JH What was the reason behind him wanting to call 0-2 pitches?

MS Because he didn’t want that ball to be where it shouldn’t be. Because sometimes I’m like, the heck with that, let’s strike the guy out and get rid of him.

JH He wants you to throw a “show” pitch?

MS He wants that pitch not to be a strike. So he made sure if I called it, that it was where he wanted it to be, and okay, go ahead and keep doing your stuff. But that 0-2 pitch, I want to make sure that we don’t get any 0-2 base hits, or that kind of thing. But he had all the confidence in the world in me, and let me call my own game.

JH How did you learn to call games? Was it just simple experience, or you just had a knack for that from the beginning? How do you develop the ability to call games?

MS I had a high-school coach, his name was Joe Voegele, and Joe came to Aiken when I was a junior in high school. And Joe was a catcher at University of Cincinnati, and Joe was only five years older than me; he was fresh out of college, and I’m this young guy. And he showed all his confidence in me, and he made me the catcher that I became when I got to the minor leagues. He just polished me, no end.

But his biggest thing was, hey, you call your own game, because it’s best for you to do that. And it was more prevalent back then. More catchers called their own games than coaches calling the games back then. So it was kind of a norm. So when I got to the minor leagues, basically everywhere I went I called my own game.

JH Because several of your teammates – Paul Moskau and some of the rest of them, just raved about how you called a game, and how you kept them under control during games. That was part of the leadership, even more so than maybe the clubhouse or on-the-buses kind of thing.

Marlon’s just, I mean, oh God, I couldn’t have asked for anybody better that was a catcher! He knew what I had, what I didn’t have, what to do, how to do. Knew the hitters, knew everything. Just took all the pressure off. He put down something, and I threw it. That’s kind of how we went. We were just on the same page. And he was funny, and he could keep people loose. — Paul Moskau

MS Russ Nixon told me that before I put my finger down, I had to always check where the hitter’s feet were, and where his hands were. He said, those are going to tell you what he’s capable or not capable of doing. And once he realizes that his approach is getting him into more trouble than success, you gotta make sure that you can see the adjustment that he’s making in the batter’s box. And that always helped me in regard to calling the game, because I could look at those feet: he scooted closer to the plate, so we go inside or he backed off the plate a little bit or he got deeper in the box — that kind of thing. The manager could never see those things.

And that’s what Russ always said: I can’t see it. I can’t see it from the dugout, if he’s moved an eighth of an inch closer to the plate; you can see it. But if you’re not paying attention to it, and you throw that ball outside and he hits it over the right-centerfield wall, that’s on you. That ain’t on me. So that helped me tremendously in regard to calling games.

JH It’s nice to know you had some mentors back in those days.

How about the rest of the leadership thing? Because again, so many people said, he’s the biggest leader that we had. Was that a natural thing for you, or was it something that this particular group especially took to? What do you think about that, looking at it now?

MS I had it coming out of high school, because of being a multisport player in a leadership role. Plus, I was raised to be a leader. It helped me immensely, especially playing quarterback and catching, because it requires that. And having coaches who gave you that liberty to be a such person, it always was instilled in me. So especially playing football, that was more prevalent on the football field than it was when I was in Knothole [Cincinnati’s version of Little League] and stuff like that.

JH But you being the quarterback, I imagine more was expected out of you?

MS And because I was a sophomore playing with seniors. And so being around older guys, they showed me how to lead; how to have command of the huddle and things of that nature. Which I carried into other sports, and that helped me tremendously in regard to the leadership qualities.

I always knew how to talk to people; always knew how to calm a person down, because I wasn’t a nervous person; never was a real nervous guy. So tough situations were something that I kind of relished.

But those guys that we had [in Eugene] were such good pitchers, you didn’t have to really do much back there, because they put the ball where you put that glove up.

Only thing that helped them was, I could constantly call time out and go talk to them. And we never talked too much about what was going on. It was always something else: Hey, we gotta get a beer, man; gotta hurry up. Or you gonna play cards tonight? or what you going to do? But we can’t do that until you get this guy out!

JH So you had a way of working around it and easing the tension?

MS Yes, yes.

JH Because so many people told me, look, you’ve got to talk to Marlon, because I can’t imagine not throwing to him back then. And what a difference you made to them. And what a good guy you were in the clubhouse and off the field, and all the rest of that. How do you take that now, coming from your teammates?

MS I truly — it’s an honor for them to feel about me that way. Because it’s something that I never took lightly or for granted, in regard to how important it was, once we got on a roll, to understand how to keep this thing going, and the importance of it. Once it started presenting itself that we were close to setting records, and we could actually win the whole thing — but the pitching staff that we had, I mean, those guys, they could really pitch. They could really pitch!

JH Definitely. And a guy like Moskau could really hit, on top of all that!

MS Yes, he could. And John Underwood swung it pretty good, too. [.259]

But Paul Moskau probably had one of the better curves that I had seen up to that point. That breaking ball that he had was just unhittable. Un-hittable!

JH Was it tough for you to catch?

MS No, no, because he never bounced it. It was the same 11-5 break every time. And he never bounced it. But boy, could he spin it; man, he could spin it!

Underwood, his ball never sat still. I mean, it never stayed in the same place. He could throw that fastball. He was like Greg Maddux: that ball just consistently moved all the time.

Mario Soto was just a power guy. He just was a power pitcher.

JH And wanted to throw the slider, apparently. [laughter]

I got an email from [Marlon’s teammate] John Harrison, and he says,

Marlon was, in my opinion, our heart and soul. He could be a leader, and in an instant, he and Lynn Jones would be doing [comedy] routines. He kept everybody loose. He could keep a squirrely pitcher in line one moment, and be serenading Christine Wren the next.

I grew up watching Johnny Roseboro as a model for catchers. Marlon fit that mold to a T, and that’s intended as very high praise.

So there you go.

MS Oh, my goodness! That’s outstanding! That’s outstanding.

And apparently his manager wasn’t much on the dance floor, but was exceptional at his day job:

JH Speaking of Greg: how much of the success in 1975 was his doing? And tell me your general thoughts on him as a manager, as the leader of the pack, and how he ran games, and that kind of thing.

MS Well, first of all, he’s a terrible dancer. Just terrible!

JH I heard about that!

MS We catch him dancing in this bar. So the next day I’m on second, and he turns to me to give me a sign. And I started dancing just like him. He’s laughing so hard, Jim, he can’t give a sign. He had to turn his back and start facing the opposing team’s dugout. He’s laughing so hard, he didn’t want to turn and let me see him laughing. And the whole dugout is laughing; the stands are laughing.

But his calmness, his demeanor, his funny side — I don’t think he has a serious side. That helped us constantly be in a relaxed frame of mind. And he let us do our own thing, because he knew that we were disciplined. He didn’t have to police us; we policed ourselves. Our clubhouse always policed itself. But it was because he gave us that vote of confidence to be that way.

And especially – especially — when things got really tight, because we would go on a winning streak and then the next thing you know, we lose a couple of games in a row, and we’re thinking, oh no, oh no! And he would find a way to calm us down or relax us or come in with something that’s really, really funny. It’s just — two-thirds of it was him; it was him.

And his ability to lead? Oh, my goodness. I learned so much from him in regard to how to become a better leader. Because he never took things seriously. He never let us get into a frame of mind where, there’s no need to worry about this thing, because we were that good. That’s how he made us constantly feel.

JH He did say — and I did hear from a couple of guys — there was a thing right at the end of the year where he got wind that, some guys were making off-season plans while they were shooting the breeze in the outfield and stuff, and kind of called a team meeting out in the outfield and aired it out pretty good. Which was unusual for him. Do you recall that?

MS No, I don’t remember that. Yeah, that I don’t remember.

JH What did you think of Christine Wren as an umpire?

MS She was great behind the dish. I think a lot of people had a problem with her — whenever they did have a problem with her — because sometimes her feet were just a little slow. But other than that, I thought she was great. She handled herself really, really well. She didn’t ever try to personify poor me, I’m a woman. She wasn’t that way. She was tough. She didn’t take stuff off anybody.

I mean, she turned me down a lot, because I tried to date the hell out of her. I was constantly asking her out.

JH And she was constantly saying no?

MS She was saying no. She said, I can’t do that. It’s against policy. We can’t date players. That’s all she would say.

JH Well, at least she was straight-up about it.

MS Yes, yes. She was a no-nonsense woman and it was a pleasure working with her.

JH So when we look in more on 1975, was that a kind of a perfect storm of the right manager and the right players in the right place, at the right time?

MS Yes. And we had such a mixture, because George McPherson was an independent-league player who came to us, and we had guys that ended up making it in the big leagues. And because of their stint in Eugene, they got better faster, because of the caliber of manager that we had. And we had such a good fan base too. Jim, these fans were unbelievable. Unbelievable that they relished us.

JH And I guess they were an independent team for a couple of years before 1975.

MS Right.

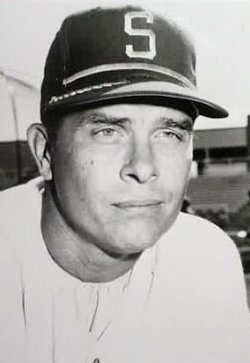

JH Greg tells a story that he was impressed — he was with Seattle originally, and they weren’t drawing flies in Sick’s Stadium. And he says, look at these people in Eugene — this independent team, they’re drawing like crazy. And Chief Bender told him to go try to get a PDC [Player Development Contract] with them. And he went in and asked them, and lo and behold, they did sign a PDC. And that’s what started the whole Eugene run that they had. And you know, the fans loved the old ballpark that they had there [Civic Stadium].

MS Yes. Yes. I didn’t know how it came about that we ended up there, but these people were, they worshipped us. And anything that we needed, they took care of it. You know, it was the talk of the town, and it was sold out, sold out, sold out — and oh, my goodness.

JH And you said George, and I think maybe Mark Lucich and John Harrison and Barry Moss also were on that team in 1974, when it was still an independent team. So that was part of the mix. And you had younger guys like yourself, you had college guys like Moskau, and Soto and all the rest. So in your mind, does that team still stand out to you, out of the teams you played for?

MS That’s the best team I ever played with. And I say that because it had such camaraderie. We all got along and as you can tell, to this day, how we still care for one another. But I mean, that’s the best team that I ever played for. First championship I ever won, too.

all got along and as you can tell, to this day, how we still care for one another. But I mean, that’s the best team that I ever played for. First championship I ever won, too.

JH And people have said that — one of the rarities, Moskau said — even in AA, it was not like it was in Eugene, where the team did support each other and want each other to do well, and not one of these I hope you screw up, so I get in and do well, and to hell with you.

MS No, no, no. I mean, because you can see talent. You can — we knew what guys were going to make it. Any minor-leaguer who doesn’t admit that is lying.

I played against Lou Whitaker, and everybody on the team said, well, we’re looking at a millionaire, guys. That guy is gonna be in the big leagues. You could see that; you could see that Moskau was going to be in the big leagues. Soto was going to be in the big leagues. You could see that Lynn Jones was going to be in the big leagues. You could see that, so all you did was you tip your hat to them, because they had something that you didn’t have.

The Emeralds’ rivals were the Portland Mavericks, an independent team whose “maverick” ways rankled a number of the Ems — especially when Eugene became a Reds affiliate for the 1975 season.

MS Portland came along, and switched to an independent team. Did you see The Battered  Bastards of Baseball? They showed the 1974 and the 1976 years, but he never mentioned anything about the 1975 year.

Bastards of Baseball? They showed the 1974 and the 1976 years, but he never mentioned anything about the 1975 year.

JH Paul Moskau, among others, says that’s because we kicked their ass! [laughter]

MS Yeah, that’s right! [more laughter]

JH All you gotta do is say the word “Portland” to any number of your teammates, and —

MS Oh, we hated them! We hated them.

JH Was it the team itself, or was it [manager Frank] Peters himself, or the whole situation —

MS It was Peters. It was him and it filtered down, because we were such a polished organization at that time. That everything had to be such a way, in how you carried yourself, how you presented yourself, how you wear a uniform, the whole shooting match. And when we played those independent-league teams that were kind of undisciplined — to use a lighter word – [laughter] we were called The Pretty Boys and you guys think you’re better than everybody else, that kind of stuff.

But I mean, the biggest lie they told [in the documentary] was that — at the very end of that presentation, he sat there and said that these organizations [brought] their AA and AAA players down, so that Portland couldn’t win a championship. That’s what he said, which is so untrue.

JH You guys didn’t need much help then.

MS This was a really good team; that Eugene team was a really good team.

JH You got 54 games in, in Eugene. And that’s — so you had to be catching, what? three out of four games?

MS Yes. And because Chief Bender — I mean, I was kind of getting to my last rope, to where they were like, Hey, you need to put up or shut up kind of deal.

When I got to Eugene, and we started rolling, me and Greg just fell in love with each other. And Greg looked out for everybody. He just – oh, my goodness, I’m sure, because Chief Bender was up there quite a bit, because it started filtering down to Cincinnati how well this team in Eugene was doing.

And so once the season was over with, I remember Chief coming into the clubhouse and he said, good job, good season this year. And I said, thanks, Chief. Is there any way I can play winter ball? And he just said, we’ll see about that. He just walked away.

1976: Final season

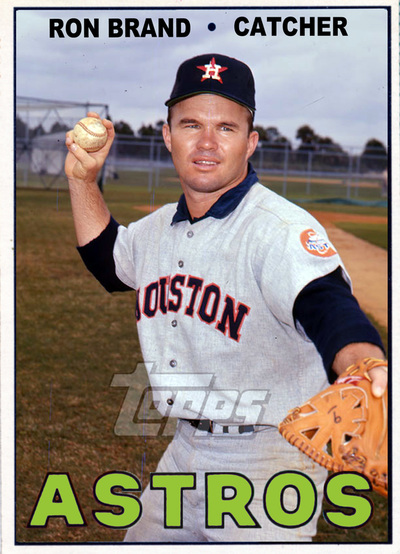

MS So then, when I went to Tampa that next year, our manager’s name was Ron Brand. And Ron was just horrible. That’s the only word I can say in regard to Ron.

JH The way I’ve heard him described was he played for Houston, among other things, and he  came in and didn’t do stuff the Reds Way, and got chewed out by Plaza, and that kind of thing. I mean, he was just a fish out of water, kind of, it sounds like.

came in and didn’t do stuff the Reds Way, and got chewed out by Plaza, and that kind of thing. I mean, he was just a fish out of water, kind of, it sounds like.

MS He was horrible. And so he was told that I had to play every day. And he told me this, and said if I didn’t perform, that was going to be my last year – they were going to release me.

So the season goes on — first couple of games I left the yard a couple of times, and the next game I wasn’t in the lineup. And so we’re at the cage while we’re taking BP, and he says — in front of all the guys around the cage — I guess you guys are wondering how a guy can get a home run and hit a double, steal a couple bags and throw out a runner, and don’t get to play the next day. And so I turned and I looked at him. I was like, no, it ain’t gonna go down like this.

So what happened was, when I got there, Russ Nixon really worked with me — because Russ was a catcher — and he showed me the finer points of catching one-handed. I had always grown up with the pillow [old-style catcher’s mitt].

JH So you had to use two hands.

MS I had to use two hands. And so once I got this hinged glove, then I still kind of, every now and then, stuck that [right] hand up there. And Russ fixed all that.

So Ron Brand was a catcher also, and he started trying to teach me a way to — it’s called sway. When you caught a ball to your left, you would move your body with you. And that was to deceive the umpire. But once you got over there, it was extremely hard to throw a runner out, because you had to get back centered, move your feet, and release the baseball.

So I told him, I said, that’s not comfortable for me, because the way Russ told me has worked out really good for me. Once I said that, it was off with your head!

And so it got worse and it got worse and it got worse to where — we were playing a doubleheader. And our other catcher, his name was Greg Dahl. And he caught the first game. There was an exhibition going on between games. Ron was going to catch the exhibition. I’m catching the second game.

So when I go in to the dugout, he asked me if he could use my shin guards. And I said, well, it makes more sense to use Greg’s shinguards, because I’m going to catch the second game. If you take them, then I gotta readjust them again. Not good.

So I go in the clubhouse, change, come back out, look at the lineup card. I’m not on the lineup card. Greg’s catching the second game also. So at this point, Jim, I said, you know what? I think it’s time for me to go home and just leave this alone. I was going to quit. I had made up my mind that tonight is my last game. After this, I’m going to ask for my release and I’m going home.

So the game goes on, it’s a little tough. It’s a real tight, close game. And he looked down the bench and he says, Styles, go get so-and-so up in the bullpen. I just sat there. I didn’t move, and I said, I’m not doing nothing. After this is over, I’m outta here.

So — and this is during July — and he looks down at me again. I ain’t moving. He said, I said, go get so-and-so up. I just sat there. I didn’t even look at him. And so Donnie Lau was my roommate and he goes, Man, don’t worry about that. Don’t worry about that. I’ll go get him. So he ran down there. So Brand is breathing fire.

And after the game was over with, I went in the clubhouse, I started packing my stuff. And he comes over to me, puts his face in my face: I want you in my office right now!

So he brings me in his office, slams the door, and just starts cursing me. Oh boy, he cursed so bad: Who do you think you are? and you think you’re this? You think you’re that? and you’re the worst catcher I have ever seen!

And you can say a lot of things to me, but once you told me that I couldn’t catch, that — I just fired back at him. I said, my father doesn’t curse me. I ain’t gonna allow nobody to curse me. You’re a terrible manager.

And he flipped his desk over and he said, I’ll kick your ass in here!

I said, you put your hands on me, it’s not going to be good for you.

So I said, all I want is my release. That’s all I want. I want to get out of here. And so I left the room and I slammed the door and I went on into the clubhouse, started packing my shit. So I’m thinking, you’ve gotta call Chief, and they’re gonna release me. Well, they didn’t.

So as I’m coming out of there, Donnie Lyle’s waiting for me. He says, come on, man. Let’s go. I said, no, Donnie, I need to walk. Where we lived wasn’t too far away, and Donnie had a car. I said, I need to walk, man. So I’m walking, I’m walking. First phone I see, I call home, and it’s during 4th of July. And my Mom answers the phone, and I start crying like a three-year-old baby.

JH Uh-oh!

MS They tell me I’m terrible! I can’t do this, I can’t do that. And she screams through the phone: that’s the way of the world! And she hung up the phone.

JH Whoa! A little tough love from Mom! That is cold!

MS I’m inside that phone booth. I mean, I can remember this like it was yesterday. I’m sitting inside that phone booth, and I’m the only person in the world right now. That’s the way I felt. Nobody loves me. Nobody cares about me — being a little selfish brat, that’s all I was doing.

So I got back to the hotel, and me and Donnie talked, and everything. So the next day, I went back to the ballpark. And I’m thinking for sure that he would have my release papers and my plane ticket, but he didn’t. So he comes up to me and he tells me, I still got to play you. You better do this and you better do that.

Okay.

And so I ended up doing pretty good. And at the end of the season, he comes over to me and he puts his hand out as I’m clearing out my locker, and he says, I just want to shake your hand. I know we had some rough times – and I said, you need to stop. And I stood up.

I said, this is the last professional game I’ll ever play. They’re going to release me after this is over with. And you had no good part in this at all. You hurt me more than you helped me, so you can’t come and talk to me about anything. And I turned around, put my bag on my shoulder, and left.

In January of 1977, that’s when they released me.

JH What a way to have it end! I will say this: at least you got to say your piece to the man.

MS Yes, yes, yes. Oh, he was so horrible. He was horrible. And he had the Little Man Syndrome, too. He was a short man that, you know, he stuck his chest out there to everybody.

JH A little Napoleon thing going there?

MS Oh, my goodness. It was bad. It was really bad.

JH The fiery Ron Brand, they would have said in those days. Yeah, okay, he was fiery, all right.

He should have been fired.

MS He hurt a lot of players. He did.

JH It’s been interesting — speaking of hurting a lot of players — what’s your take on Ron Plaza? Because there’s real polarized opinions on whether he hurt or helped players. Some people say they needed tough love and other people say, boy, he derailed some careers by being abusive. What do you think of that?

MS I loved Ron Plaza. I loved him. And he cared about me, because he had seen that I had some talent and he tried to promote me as best as he could.

When we were going up to Tampa, he drove me up there and he said, you’re going to do well. I got faith in you, and the whole shooting match. And he always looked out for me. And then when I got released, I was at a game at Riverfront Stadium and he was coaching for us then. And so he’s walking toward the bullpen. And I yelled at him, Ron! Ron! He came over and he shook my hand. He said, you had the best hands I ever saw, Marlon. We talk about that all the time. And he was such a kind man to me.

But to some guys? Whoo! You got on his bad side, hmmmmmmm!

Marlon hit .224 in his four-season career, with 9 home runs and 80 RBI.

JH When you look at your career, do you think the offense was what held you back?

MS Yes.

JH Your teammates all talk about, he can call a great game. He’s such a comfort to throw to. You can look at the stats and see that the passed balls went way down after 1974. So obviously you fixed the receiving part, your hand got better, and all that.

Being a catcher in the Reds system in those days, and without a lot of power –

MS I never hit.

JH — and you’re behind Johnny Bench and Bill Plummer, I could see where a lot of guys — you think of guys like Don Werner and Bob Barton, and some of those kinds of guys who — they might as well just pack it in, because they were not going to get a shot. But do you feel like your receiving was major-league caliber?

MS I do. I could catch with the best of them, and then I can throw with the best of them. But I just never hit; never hit.

JH Can you put your finger on why that was?

MS I didn’t know which eye was dominant. I just found out, probably about five years ago.

JH I’m guessing, then, if you’re a left-handed hitter, you must have been left-eye dominant.

MS Right. I am.

JH That used to be the thing, was to open guys’ stances up so that they could get more of both eyes on the ball, and kind of compensate a little bit. It’s like you’re backwards at the plate.

MS Right! And I started reflecting back on what I was looking at while I was hitting. I told my son, I’m eight times the hitter today than I was back then, because I’m more knowledgeable about hitting. Back then, I hit from memory: I saw the ball out of his hand, but as it was presenting itself to me, I never saw it when it was hitting the bat. I didn’t see it, because my eyes were still out there between home plate and the mound. My eyes were still out there. It wasn’t tracking the baseball all the way down to —

JH You weren’t completely tracking it, right?

MS Right. No, I was not.

JH Left-handed hitter though, but a right-handed thrower. What made you start out lefthanded, and did you ever think about going right-handed?

MS No, I was more lefthanded than I was right, growing up. And you were deterred [from] being left-handed when I was a kid. Everybody tried to make you right-hand dominant. And so as I grew up and I just put everything in my left hand, they started making me do other things right-handed. So I hit left, throw right; shoot a basketball right. Shoot a gun left. Write left. Eat left. All over the place.

JH Which way do you brush your teeth? [laughter]

MS Right-handed. I drove left.

JH Brooks Robinson said that he thought one of the reasons that he was a good fielder was because he was ambidextrous — that he did all kinds of stuff lefthanded, but he hit right-handed and threw right-handed. Otherwise, a lot of his more-natural way was lefthanded.

When you hit pro ball, was it a dramatic difference as far as being a left-handed hitter with how many lefties you saw?

MS Didn’t see very many.

Facing the End and Moving Forward: 1977-2020

JH When you got done in 1976, were you all right with, okay, look, I’ve taken this as far as I can? Did you consider going back? Did you get offers to go back? It was kind of sour the way it finished, but what was the aftermath like for you?

MS Chief Bender called me at home in January of 1977 and he told me that they were gonna release me — give me my full release. He said he was sorry, and he thought the world of me and the whole shooting match. So I knew it was coming.

But I went down to the stadium, because at that time Larry Starr was the [Reds] trainer, and anybody who lived in the Tri-State area could work out during the offseason. And so all my stuff was down there.

So when I got down there, Brooks Lawrence was in the front office. And so I went up to Brooks’s  office after I got my stuff and I said, Hey Brooks, I got my release, and I just want to thank you for everything that you did, and that kind of thing.

office after I got my stuff and I said, Hey Brooks, I got my release, and I just want to thank you for everything that you did, and that kind of thing.

He says, I can make a call right now and get you on another team. At that time, my daughter was three years old; I had her when I was in high school. And my father is a huge family man. And I knew what Dad would say: you had your run at this.

When I got drafted, my father didn’t want to sign the contract. I was drafted in the fifth round, and the Reds offered me $5,000, which was no money at all. And there were guys who got drafted in the 14th round that got more than me.

But my father said, you need to go to college because no one in his family had ever gone to college. And so that was a big stickler with him. And so I took him in the kitchen and I said, hey, you know, if this doesn’t work out — but I’m sure I’m going to make it. Word for word, I said, I’m sure I’m going to make it, but if it doesn’t work out, I’ll promise you that I’ll go to college. Biggest lie I ever told to him.

So fast-forward to this conversation that I’m having with Brooks Lawrence. And I said, no, no, Brooks. I know once I go home and tell my Dad what has just happened, he’s going to say to me, okay, you had your run at this; it’s time for you to take care of your family. Cause you got a daughter, and you gotta settle down and become a family man.

Now, I knew that’s what he would say to me. So I never explored trying to get on with anybody else.

I regret it. I regret it.

JH Do you think that you didn’t quite empty the chamber, as far as playing goes?

MS Yeah, I regret it, because I came off a pretty decent year in Eugene, and then Tampa was — it finished up okay. But I knew I still had something left. But I knew that my Dad wouldn’t buy any of that, in regard to me having my daughter.

Marlon’s work as a scout and Reds Urban Youth Academy volunteer has brought him a great deal of satisfaction.

JH Did that set you on a path that eventually led to your work with the Reds now, and the Urban Youth Academy, and all that?

MS Well, one of my really good friends, his name is Denny Nagel — the right-handed Denny Nagel. Denny has been scouting for the Reds for 41 years now. And during the time when he was scouting, the Reds had a need for an inner-city scout. So Denny was asked if he knew anybody, and he told them about me. And so they interviewed me, and they hired me in 1997. And that was my sole purpose, was to scout only in inner-city.

As time went on and the inner-city talent level got really, really bad, they started venturing me out into other states. But it was all because Denny recommended me.

JH Has scouting and your volunteer work been as rewarding as playing, or do you feel like you’re able to have an impact there?

MS It’s been an unbelievable ride, because they’ve given me such freedom. I oversee 16 Recommending Scouts that are underneath me, and I run all the tryout camps for this region for the organization. They’ve given me such liberty to enhance the organization that I just can’t tell you how indebted I am to them for giving me all these opportunities. And so once that came along and our Academy was built in 2014, I volunteered. I told them, anything you need me to do,  I’ll do it. I don’t want to get paid; none of that stuff. I just want — everything that’s in my mind was given to me for free, so I want to give it back for free.

I’ll do it. I don’t want to get paid; none of that stuff. I just want — everything that’s in my mind was given to me for free, so I want to give it back for free.

So I started volunteering over at the Academy and helping them with some things, and giving them some insight in regard to how scouting works, and bridging the gap between getting guys drafted and noticed, because no other major-league teams go over there and see those kids, because they’re all inner-city kids.

The Academy has been such a fulfilling opportunity for me, and we have a director of our Reds Community Fund — his name is Charley Frank. And Charlie is — I would die for Charley. That’s my definition of how I feel about Charley Frank. He is one of the greatest men I’ve ever known. His direction over there, and the team that he put together, has taken that place to the heights that Major League Baseball is [modeling] that Academy in regards to how they move forward with building the other ones just coming up. It’s all because of Charley Frank and how he cares about urban and all youth – not just urban youth — he shows it in his body of work over there.

JH And he was the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Man of the Year, a year or two ago.

MS Yes. And Kim Nuxhall and I, we played together my first year in the minor leagues.

JH I had forgotten about that. He’s a friend of mine, also. Did some volunteer work, helping him out at the complex out there for a couple of years.

MS Jim, we gave ’em — three years ago, was it? We gave all the kids professional contracts. Every one of those kids at the Miracle League, we gave them contracts. The Reds drew them up, and I presented the contracts to all of them. It was unbelievably fabulous. The work that they’re doing over there, my goodness!

JH Yes, it’s really something.

Excerpted from my upcoming book The Little Red Wagon: The Amazing Story of the 1975 Eugene Emeralds