In Part 1 (story here) we looked at the playing career of John Harrison, member of the 1975 Northwest League champion Eugene Emeralds — the “Little Red Wagon” to the parent-club “Big Red Machine” Cincinnati Reds.

In Part II we look at life after baseball for John; some of his influences; and what made the 1975 Ems a special group.

JH What kept you from coaching professionally?

John My first wife was very patient with me being hyperfocused on baseball, but by the same token questioned, I think, at some point, whether or not she wanted to be a baseball wife.

She never gave me an ultimatum, but I felt that at a certain point in time, especially after the Victoria experience and then having my arm pop during my tryout, kinda going, maybe I should just grow up, get real, and do something else.

John did do “something else” and it shaped his second career.

John When I went back to school, we moved up to Oregon and I finished my degree, and then got my Master’s at Oregon State University. I went into teaching, and I thought I was going to be a high-school/college coach and pick up a few PE classes on the side.

While I was doing my undergrad, I coached varsity baseball at South Albany High School in the neighboring town to Corvallis where I live, and I was the assistant coach there for three years — partially because my responsibilities were around my education, and since I wasn’t an employee of the school district and I was getting my degree work and I was also playing Mr. Mom to my daughter, I didn’t want all the responsibilities that high-school coaches have, which include being the head groundskeeper and the head fundraiser.

But I got to wield my chops, I suppose, working with — they had no feeder program at South Albany. They had no summer program to speak of. Most of the kids drove combines or worked in the fields during the summer; they didn’t play baseball.

And the first year I was there, I kind of came in midway through the season; their assistant coach quit, and they had a wretched team, and I just basically worked with the coach. The second year, when they asked me to come back, I said, okay, but I’d like to make a few suggestions and requests.

And they said, well, do you want? And I said, I want to run the team on the field; I want to run the practices; and I want to be the strategist – the head coach during games. I will run everything through the head coach, but I want to give the signs; I want to devise the plays; I want to run the practices. And the head coach goes, well, what do *I* do? And I said, I’m going to teach you how I was taught. And I was taught by the best there are. So I’m going to give you a head-coach’s clinic all season; that’s what you have.

And he very generously said, okay.

We played .500 ball for the next two years. It was the first time that school had ever played .500 ball. We beat the eventual state champion three straight. We actually started sending kids to college programs to play.

What I did was teach the kids the nuances that I had to be a master of, because I didn’t have size and strength. I taught my kids to play that way, and we just played real smart baseball; we stopped beating ourselves. And I had a ball doing it.

Coming down the home stretch toward graduation, I got a call from Western Oregon State College. Their head coach was retiring, and he had heard about me from one of the boosters at South Albany High School; about what a great job I had done over there, with their program. He wanted to interview me about coming up and interviewing to be an assistant coach, and possibly taking over the program.

So he came over to my house, and I did a two-hour interview with them and talked about my philosophy and my experience. And he offered me the assistant coach’s position. But to do that, I would have had to quit school, and there wasn’t — because I didn’t have my degree, there were no teaching assignments. So it would’ve been a financial thing.

Then I talked to my mentor, who had been formerly been the head tennis coach at Western Oregon, and she said, I know the coach; I know what he’s promising you; but when he retires, the next coach, if it’s not you, is going to bring in their own guys. And has he talked to you at all about recruiting? And I said, he mentioned it briefly. She said, because you’re going to be on the road constantly, watching and recruiting in rural Eastern Oregon, rural Western Washington, Idaho, and Montana. You’re not going to be home. And then I said, and I’ll be divorced in six months.

So she said, you have a decision to make. You either want to be a teacher, or you want to be a coach; you really can’t do both right now. So I chose teaching, and I never looked back.

It’s one of the best decisions I ever made.

JH Really?

John That was a “big boy” decision for me, because I had spent my entire life dreaming about being a coach, a manager. So I just ended up coaching girls’ soccer for my daughter’s team, and had a ball with that. And that was the end of my coaching career. I became a school counselor.

JH Any regrets on how that worked out for you? Are you okay with how it all played out? Do you still miss baseball?

John Well, I went through that period of about three years where I wouldn’t even watch baseball on television. I mean, not even the World Series. Because I was embittered. I did not like the business end of baseball.

Everybody you talk to — I’d say 90 percent of former ballplayers — say all they needed was a break and they could’ve made it all the way to The Show. I’m one of those guys.

George Genovese drummed it into my head, and I believed it: if somebody had let me play 135 games in one season, I think I would’ve made it to the major leagues. I think I was that good. But I didn’t.

I wish I had gotten a chance to play professional baseball when I was in my thirties, because that’s when I was in my physical prime. And I know because during the winter and during spring training, my game tended to elevate with who I was playing with. If I was around major-leaguers, I played at that level; and I think I could have played. But that’s my story.

JH Sometimes you play like who you play with.

John Yeah, exactly.

JH So all in all, the playing career you had — you wished it could have been longer; wished you could have had more “champions” in different organizations. But it does sound like it helped you out a lot for the rest of your nonbaseball career.

John Oh, I learned as much playing baseball as I learned — you know, it’s a great teacher. Life is a good teacher. But the hard lessons are sometimes the best lessons.

I went on and I was in education for 27 years; was a counselor for 13 years. I was accused at times of being an innovator, and it was just what I wanted to be. I wanted to be that with baseball, but I guess I went on to bigger things in a way, because I was dealing with families and kids, not the outcome of games, but the outcome of life. And I felt very well-prepared from it.

I think that the edge that an athlete has — I mean, it’s not like standing in front of gunfire, but it’s next. How many people go to work and get booed or cheered?

JH What kind of things were you aiming at, or trying in counseling, to make a bigger difference there? How did you go about that?

John Well, when I left, I was a big proponent of trauma-informed schools, because we saw the impact. We saw kids coming to school that — they weren’t learning, they weren’t getting along. Something was missing. And then my motto, always, with teachers was

Don’t react to the behavior that’s right in front of you. There’s always a backstory. There’s a reason why they’re acting that way. That can be anything from the fact that you’re confronting them and they’re embarrassed, and so they’re lashing back, to they haven’t eaten today or last night.

I just started to see that. And so I was a big proponent of we need to be more informed. Otherwise, we’re always in a reactive mode. You know, in Oregon you’re always dealing with resources. Budget cuts. I think I got laid off the first five years of my teaching career.

And just like baseball, I kept coming back, because I thought that was my calling.

So you learn to be resourceful and resilient. These are also things that I know I got from playing baseball. I’m a student of life, I suppose. And baseball was a great education on getting along.

By the same token, to a lot of people, they saw me as a dumb jock — and I’m not dumb. But I also learned, like I did when I [would] walk up to the plate weighing 140 pounds, they can giggle and dismiss me all they want to. But if I get on first base, I’m scoring. And I kinda did the same thing when I encountered naysayers as a teacher: just because I teach PE doesn’t mean I can’t teach; doesn’t mean I don’t reach kids. It just means I hold a ball rather than a book.

I told John about my friend Kim Nuxhall, who was a minor-league pitcher/shortstop in the Reds organization at roughly the same time John was drafted. And like John, he played a couple of seasons and then went into education. Today he is retired from teaching and devotes much of his time to the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League in Cincinnati, which gives persons with special needs a chance to play baseball.

JH Kim retired out of elementary-school teaching, and he had the same complaint: look, I was a PE teacher for 25, 30 years. I do a lot more than roll out the balls and blow the whistle. But his thing was to focus on character education, and that became his passion and his difference-maker for his teaching career. Eventually it springboarded into him operating the Miracle League complex.

John Special-ed teachers are my heroes.

JH Kim also developed his own programs and really tried to accelerate the development of the character-building and character education and all that stuff.

John Well, part of my thing was also, we need to find ways to enthuse kids. They need to come to school enthused to be here for more than just to see their friends. So there’s a spark about learning that they can learn somewhere.

One year, my principal was trying to fill out my FTE [Full Time Equivalent], giving me electives to teach, and he finally filled out my last missing piece of FTE with: you’re gonna supervise the gym at lunchtime. Well, I hated that, because it was unstructured. All the rules of the gym went out the window, and it was just all behavior correction. And I hated that because it made you the man. Made you “the mean guy” or whatever. I hated that.

So I went home and I said, I can’t do that. So I wrote a proposal for an elective class, and I went to the principal and I said, I’d rather teach an additional class than supervise the gym at lunchtime. He said, what, another PE class? I said, no, an elective. He goes, really? What elective? And I knew he was a guitar player, and I’m a guitar player. I said, I’d like to start a guitar program.

Now, I’m a guitar geek. That’s my passion now. Music is my passion.

INFLUENCES: RIDDOCH, WOODEN, BRAND, PLAZA, RAPP

Greg Riddoch was the manager of the 1975 Eugene Emeralds – and later, the San Diego Padres. He had a profound influence on many of the players he coached and managed – John Harrison among them.

John I know I thought it at the time, but one of the things that strikes me now is how Greg was only four or five years older than us, but he — first of all, he was a college guy. He was married and he had a couple kids, but he just had a maturity, a presentation. And he was flip and funny, so he was one of us in that regard. And you could feel chummy with him, but you also knew that there was a dividing line. Total respect. But he provided an aura that was more of a big brother or mentor than boss. And you trusted him implicitly.

And you could always hear the wheels turning. He’s always thinking about three or four other things at the same time — no matter what’s in front of him — with great clarity.

The first conversation I had — real conversation, one-on-one — with Greg, I was still hurt and I went in early to the ballpark; we were in Sick’s Stadium in Seattle. I think I was doing some weight-training or hot-tub or something with the trainer. And Greg came in as I was getting ready to go back to the hotel, and this was like the first time he and I had ever had a one-on-one, “so tell me about yourself” chat.

And he said, so how long have you been playing shortstop? or how long you been playing second base? And I said, since the beginning of the season. And he stopped in his tracks. He said, what? I thought you were a second-baseman. I said, I played a few games, Greg, at second; I was a centerfielder in college. I was converted to a shortstop when they drafted me. My experience as an infielder has been as a pro. So this is the first time I’ve ever played second base.

And he said, well, how do you like it? And I say, I like it fine, as long as I play. That’s what I care about. I want to play, and I want to help the team. And he said, so you’re a shortstop? And I said, yeah, that’s what George Genovese said when he asked me if I was interested in being drafted. So I’d have to say that’s my favorite position.

And he said, I’ll see if I can get you into some games at shortstop. So I played a few games there during that season. Not many, but a few.

JH You mentioned respect. And especially for young guys who haven’t learned that they don’t know everything yet, that’s really not easy for a coach or manager at that level to get from players sometimes. How did he earn your respect?

John Well, it’s hard to manage people, in any form: supervisor, boss, manager. It’s hard because there’s always this invisible barrier. You have to maintain a certain distance as a manager; you might have to release that guy.

So I know how hard that is, and I didn’t know at the time — my career was in education. I became a teacher, and then I finished my career as a middle-school counselor. And so in a way, I’m an amateur psychologist. I identified with Greg about that, because I knew he had a background in psychology.

There’s a lot of guys that when they manage or coach, they bellow; they scream; they yell; they intimidate. I’m not a big Bobby Knight fan.

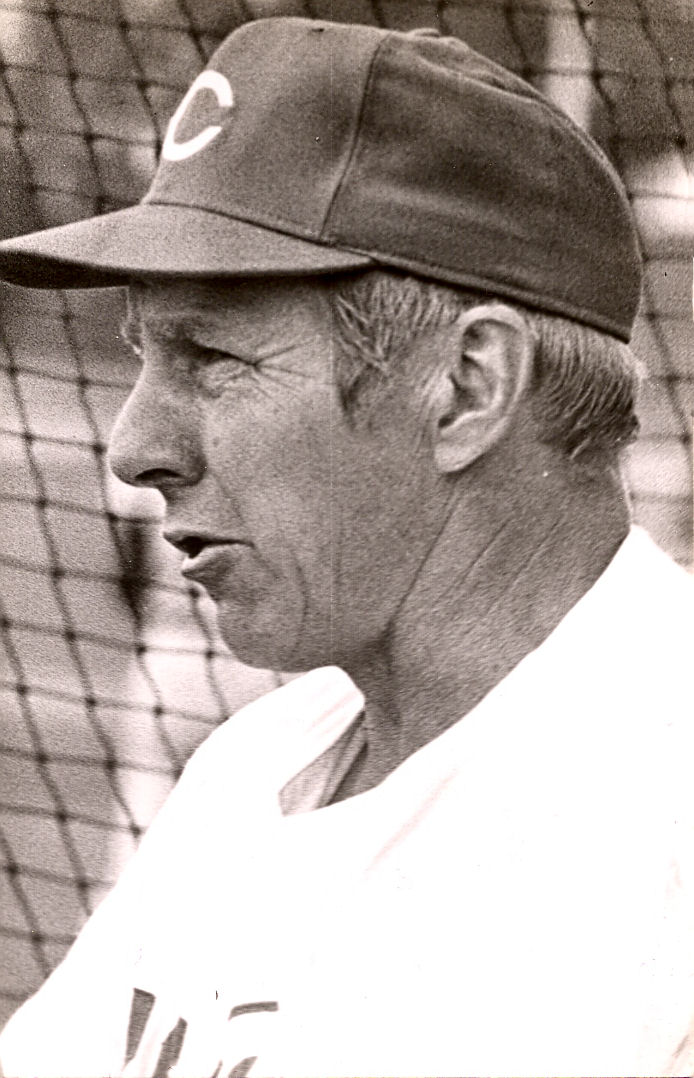

JH [emphatically] NO! Or Ron Plaza. Let’s put ol’ Ron in there. Wow! The stories I’ve heard about him — holy cow!

John Yeah. Ron had a gear where he could back it off and be decent. But Ron was — the Reds were very, very militaristic. Especially with the uniform. Your hair was cut a certain way. The socks were a certain height. The pants were a certain height. Everybody looked the same. Ron Plaza was the only guy in spring training that didn’t have his hat on. Pete Rose was the only guy in spring training whose hair came over his ears.

And Ron was always this tough guy — always portraying this tough guy. And I don’t know if he was military; if I was going to guess, I would say he’s probably a Marine.

JH Sure seems that way.

John But he played that, and he never showed his humanity — very, very seldom. And he had a tic, where he’d blink a lot. So one of the nicknames that people had for Ron Plaza was Chief Blinky. He had a certain cadence in the way he talked, and he had a certain stance.

And when Ron was going to hit you fungos, he would strap on a pair of black leather batting gloves. I remember one particular workout, I get over at shortstop and the first ball he hits is on the right-field side of the second-base bag. And it’s one skip on the edge of the grass; the next bounce was beyond second base. The second-baseman might’ve had a shot at it; I had none. I took two steps, stopped, and started to go back and he says, Oh, is that how this is going to be?

The next one he hit was farther over toward second base than that one.

And I said, okay, this guy wants to see me bleed. So I was diving, tumbling, scrambling, anything I could do to get at whatever he hit, including trying to anticipate where he was going to hit it so I could get an early jump.

He expected your best, and he got it. But there was a certain cruelty to it.

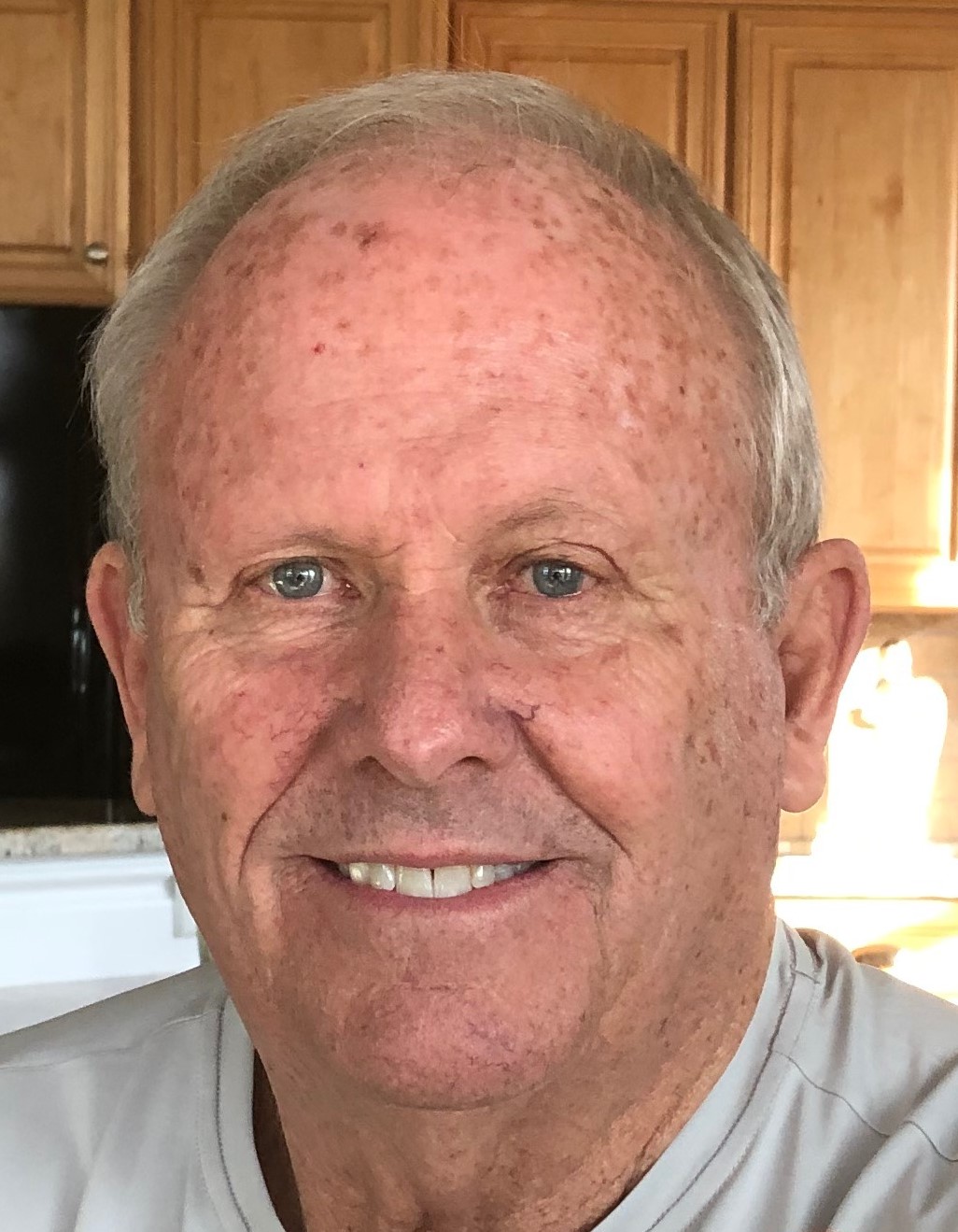

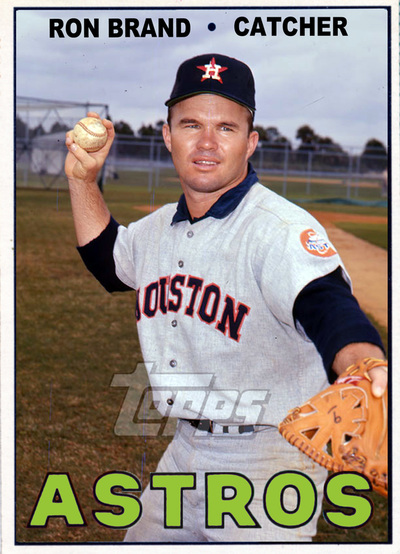

In Part I, we discussed John’s time playing for Ron Brand, who was not previously a part of the Reds organization, and who didn’t follow “The Reds Way” regarding infield instruction: a uniform way to play that was taught to all Cincinnati farm teams.

JH I’m amazed that Brand — I wonder how long he actually lasted.

John I think two years.

JH I mean, you cross Ron Plaza — as a player, coach, manager, anything — I just can’t imagine that working out very well for you. You talk about a bad career move!

John Brand did something in one of the spring-training games I played in, and Plaza undressed him publicly, on the field. And we were like, damn, who do we show loyalty to? Cause our manager just got bitch-slapped!

JH [laughs hysterically] That’s a good way to put it! [more laughter] Well, if anybody was going to do the bitch-slapping, it probably would have been Ron Plaza.

John Oh, there was not a hint of nonsense involved. It was purposeful, and it was pointed. It was scary. I mean, part of me felt embarrassed for Ron Brand, as much as I could muster. But he was coming in, I mean the — in between my first and second year, Vern Rapp took the manager job with the St. Louis Cardinals. I had played for him in spring training the year before, and he liked me. Roy Majtyka came over from the Cardinals, I think and became the AA manager; Jim Snyder went up to AAA.

Greg wasn’t in spring training. Ron Brand, who I was playing for, brought two of his own shortstops into the camp. It was like, I have no friends here. I have no supporters here. I pretty much knew from my conversation with Sal Artiaga, I was there for two weeks at best. It was surreal.

Ron Brand was acting like an outlaw. There was a Reds Way, and he wasn’t following it. And so you’re out there going, what should I do? Should I do what he says, or should I do what they know the Reds want us to do? It was hard. It was very distracting.

JH Because they were so homogenous as an organization. And how in the world did somebody like that even get hired?

John I’m sure he was a baseball manager. He was knowledgeable, but he was not versed in the Reds Way. He wasn’t picking it up, anyway.

JH You said that Vern Rapp liked you. Vern Rapp and Ron Plaza seemed to be guys that are really sort of polarizing — guys either couldn’t stand them, or they loved them. How was your relationship with Vern Rapp?

John Really good. Somebody told me — a guy named Sonny Ruberto, who was a career minor-league catcher — basically told me, I was warned about two things: Sparky Anderson’s TV talk, and Vern Rapp.

He says, Vern Rapp is going to come up to you, and he’s gonna ask you how you’re doing, and there are only three acceptable answers, and two of them are unacceptable: Good, better, best. You better be able to back up your answer. So if he says, ‘how you doing today, John?’ If you say, ‘good,’ he wanted an explanation. That was not good enough. If you said, ‘better,’ there better be what you were going to do to get to ‘best.’ And if you enthusiastically said, ‘I’m the best I can be, Vern!’ he loved it. He loved that stuff.

I thought Vern had a facade of that sternness. I know he had a temper. I know he had a very active BS meter, but he had a heart. And I picked when I was with them in spring training; I was his shortstop. I picked.

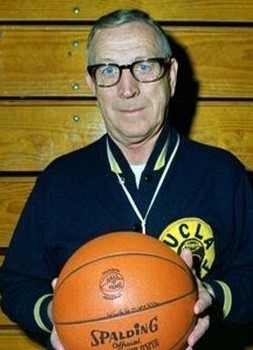

John saw the other side of coaching, too, when he encountered a basketball legend.

One of the blessings of my life is, one of my summer jobs, I worked at Westwood Drugstore in Westwood, California, just off the UCLA campus. And the guy that owned the coffee-shop part of the drugstore, a guy named Hollis Johnson, his two best friends were Jerry West and John Wooden.

So I’m the stockboy for Westwood Drugstore and I’d come up with a load of stuff to put on the shelves and there would be Jerry West or John Wooden coming down the hall. And I have to kind of stand sideways to let them go past.

I met John Wooden, got to know him the second time I met him. Second day, after I introduced myself to him, he knew my name. He remembered what school I’d been to, and he had called to talk to my coach to tell him how much I had impressed him.

That’s John Wooden.

JH Man, that’s heavy-duty!

John Yeah, that’s my hero. But John wouldn’t — didn’t yell at his players. He crumpled a program in his hands. He strangled it to death, but he didn’t belittle referees. He didn’t badger and bully and intimidate. He did it with focus and with expectation and with teaching. And that’s how I — I wanted to be the baseball version of John Wooden. That was my goal.

JH Good for you!

John So the biggest disappointment I had, was that I wanted to do that as a professional and I ended up doing it in high-school and amateur softball, and finally coaching girls’ soccer — with John Wooden and George Genovese and guys like that as my role models, and Greg Riddoch as well.

But back to Greg, because I wanted to finish something about Greg, too:

This is a very meaningful thing to me, is: After the game where we beat Portland to win the championship in Eugene, where they called me into Greg’s office, that night I was watching the news in Eugene on television, and they were talking about us winning the championship. And they were interviewing Greg and the interviewer said, “Greg, what was the key to the Ems sweeping Portland?” And without a beat, he said, “John Harrison’s defense. He came in and filled in for Barry Moss, who – when Barry got hurt, we lost a lot out of our game. John came in, and his defense turned the tide in the series.”

And I went, I mean, I gushed up. I was speechless. For all the disappointment that there was — that there is — in a minor-league baseball career, the fact that I got to play on two championship teams — and I played on championship teams in every level that I played in, Little League through college, through pros — I’m a winner. That’s the one intangible that’s not in any of the books. I am a winner, and I’m a contributor to winning teams.

But the affirmation that I got from Greg, the affirmation I got from George Genovese, I can put that in the bank. That’s something that nobody can ever take away or diminish.

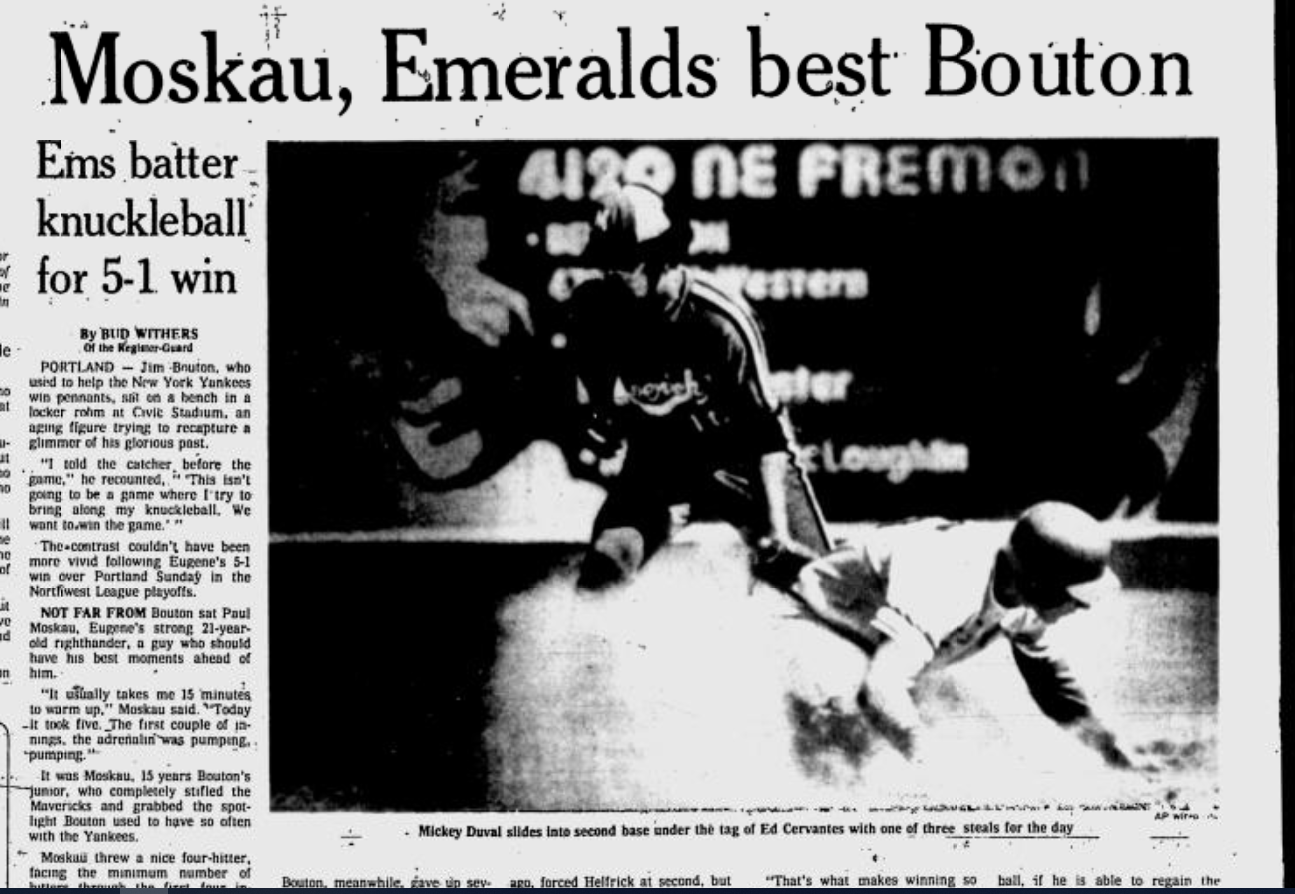

And as nice it was to hear Greg say that, I can also say he could have talked about Lynn Jones hitting a home run off of Jim Bouton that they’re still looking for; it’s still going down some street in Portland. He could have talked about Paul Moskau, how brilliant he was, but he didn’t. He talked about me, and defense.

I mean, I saw Brooks Robinson play. I know defense can turn games around. I saw Ozzie Smith play. [But] for him to say that was so meaningful to me, and such a sense of feeling like nobody was paying attention, and then to find out somebody was paying attention, and gave me some credit like that –

But it’s the way that he did it. He always treated people — he never yelled and screamed at people. He never yelled and screamed at umpires. There was always a measured quality to it. He could be cutting; he could put people in their places. But it seemed he had this rare ability to kick you in the ass while he was hugging you at the same time, if you know what I mean.

JH Sure. I understand.

John There was a lesson involved, I suppose. There was a humanity to it, a humility to it, that was pretty rare in professional sports, from my experience. And I think if you look in the dictionary under gentlemen, I wouldn’t be surprised to see his picture next to that.

JH That sort of sets him apart from a lot of baseball people, doesn’t it?

John Yeah. I don’t know that Greg was the greatest baseball mind I ever encountered. I wasn’t around him enough to say that we won because of strategy; I really don’t know. It’s very possible. But he got places that maybe some people were surprised he got to. I’m not.

I just think he had a really unique skill set, and reasonability and intelligence and emotional intelligence; a humanity about him, where he was — he was just there and present all the time. And like I said, he’s only, what? five years older than us? That seems impossible.

JH He’s always said that being a teacher was the most-important thing to him. Regardless of what he was teaching, that being a teacher and imparting knowledge and that kind of stuff was his biggest goal — his biggest desire. So maybe the baseball diamond was another classroom, in a sense.

John Well, I’ll tell you another great man that said that. And I guess I’m calling Greg Riddoch a great man — another great man that did that: John Wooden.

JH I thought that’s what you were going to say!

John Teacher first.

JH Yeah.

I understand the idea that people are surprised like that Greg made the majors with the  Padres. And he’s said, geez, you know, that was never in my plan, but you wonder if he was almost too decent of a guy to succeed in that spot. Because it seemed like the Padres players kind of turned on him at some point, and things just — he didn’t have support in the front office, either. People looking to feather their own nests and all that — like we’ve all heard a million times in baseball. But you wonder almost if he was too decent of a guy to survive all that.

Padres. And he’s said, geez, you know, that was never in my plan, but you wonder if he was almost too decent of a guy to succeed in that spot. Because it seemed like the Padres players kind of turned on him at some point, and things just — he didn’t have support in the front office, either. People looking to feather their own nests and all that — like we’ve all heard a million times in baseball. But you wonder almost if he was too decent of a guy to survive all that.

John Based on experience, I can’t rule that out.

I remember when we met in Cincinnati for a reunion about five years ago, and Greg was recounting the Marge Schott years with the Reds. And I mean, my jaw hit the floor. And that he had to engage in the sort of — I’ll use the term negotiation for fundamental stuff that they were penny-pinching.

When you put your heart and soul into something, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment, too. Because you find out not everybody else is. They’re in for other motives or other reasons.

When Greg tells the stories about those experiences, I perceive the heartbreak. And the dumbfoundedness, the betrayal, or whatever it is. Because I hate to say it’s endemic in the game, or in the business, but I suppose that’s how it’s been done.

John The Giants lost me when they did George Genovese dirty. That’s another – it’s why I can’t rule out Greg getting treated underhandedly, is how the Giants sort of “retired” George Genovese; kind of put him out to pasture, when he basically built their franchise for a decade. George Genovese was a Branch Rickey disciple, and maybe the last great Branch Rickey disciple in baseball. And it’s kinda the end of that bloodline.

But I prefer the game to the business. That’s what got me back watching it. That’s what got me back loving it. And I do love it. But I grew up mocking the Reds — their haircuts, the way they wore the uniforms — to being part of it and going, this is how it should be done. They had a strategy; they had organization; they had plans; they were well-managed. They had coaches for everything in spring training. I mean, they had sliding coaches and everything.

And then, doing my tour of the circuit starting at one step from the major leagues in spring training, standing on a field right next to Rose and Morgan and Pérez and Bench and Bob Bailey taking batting practice. I’m hanging with Danny Driessen. Sticking around in that organization, and feeling part of something. And then, when they won the World Series that year, it was like, aha! I’m a Red! To then watch Schott dismantle it — to debase it, is probably more apt — pretty staggering.

JH I doubt I will ever have a feeling in baseball, much as I’ve loved the game since I was a little kid — but those Big Red Machine teams, that was it for me.

John And we were The Little Red Wagon!

When you got to halfway through The Sporting News to the minor-league pages, we had the headlines. And that was pretty heady stuff at the time.

JH What do you think made the 1975 Eugene team particularly memorable, to the point that you are still getting together, so many years after you played together?

point that you are still getting together, so many years after you played together?

John Well, it starts at the top. Greg was the umbrella that we all stood under.

Joe Verbanic was our pitching coach. I don’t know what happened to him. I understand he’s still in Eugene, but I understand he doesn’t want to have anything to do with anything. So I don’t know if he felt he got done dirty, or what; I don’t know. But he did a fantastic job.

The funny thing is about that team is, I thought our weak point was the pitching, in the beginning of the season. I thought that was our Achilles’ heel. And in the end, when you look back at it, that was our strength.

When Paul Moskau came to us, it was like the part of The Wizard of Oz where things turned from black-and-white to color. Now we had a stopper; we had a pitcher that we knew every four days, every five days, we were probably gonna win. I think he was 10-1 or something like that. And he pinch-hit a home run in the first game he played.

We had characters on our team, but — I do a compare/contrast from the year before. George McPherson, Barry Moss, Mark Lucich, and I were there the year before, with the 1974 championship team. We came back in a very different atmosphere: much tighter, much more professional. The year before, we were fast-and-loose. This was a lot more serious, but it was at least as much fun.

My perspective is somewhat diminished, I suppose, by the fact that I felt like an outsider at one point, because I was hurt and I wasn’t suiting up. I was at the games, but I was on crutches; or I was there but not playing.

But while I worried every Friday that I was left behind, I never was. And again, I have to think that Greg kept me, and I’m eternally grateful for that, because I saw guys get released for less than being out for six weeks.

It’s just a special group of guys. We love each other. There weren’t the petty, cliquish jealousies. If you ever felt like you should be playing, the guy that was playing in front of you did something and you were rooting for him.

JH It just doesn’t happen that way, a lot of times.

John And I have to credit Greg. I had that one conversation with him after my therapy session in Seattle, and I felt like that was my bond with him at that point. Now I felt like he knew me — and I perceived a change in our relationship. They could’ve let me go, and they didn’t.

Another guy that I think had a lot to do with things is a guy named Mickey Clarizio, who was our trainer. Mickey was a college student who was our trainer both years. He’s the infamous guy who backed the bus down the service drive at Portland Civic Stadium. Which is a feat of — it’s unbelievable. I don’t think the service drive is as wide as the bus, and yet he backed it down without hitting anything. [laughs]

But we just had — we were all in it to win it, I suppose. And when we took off — I think we were 11-11 or something like that. And I think we won 40 of the next 50, or something. It was nuts. We were just steamrolling people.

And the funny thing was, in the middle of that, Bellingham lost, I think, their first 27 games of the season. The Dodgers team. They were really young and real inexperienced. I think they lost their first 20 or 25 games, and their first win was in Eugene on a Sunday against us. And the crowd gave them a standing ovation. I think that stopped a winning streak and started another one.

JH Of all teams to lose to!

John But we were just a juggernaut. And had each other’s backs, and we were just focused. I’ve never been around anything like that.

JH How much of that was the difference between being an affiliated team and not? Do you think that played a role in the difference between 1974 and 1975? Or did you just have the right guys in the right place at the right time? In some cases, it almost defies description.

John I would have to say yes, that we felt like part of something. I do think we all took enormous pride with being affiliated with the best team in baseball. I mean, for me, in spring training, being on the field right next to Pete Rose — Joe Morgan asked to use my bat one day, when I was stepping out of the cage.

I think that that affiliation with the Reds — especially that Reds team — we felt like we were part of something. We were representing, but we were also our own entity. And the next year in spring training, I detected envy, maybe jealousy, because we were all tight. That was also hard on me, being kinda excused to Tampa while everybody else was elsewhere. But I never felt like my teammates shunned me. I just kinda felt displaced. But the other guys in the organization were definitely, oh, those guys won. That’s a championship team. So I think we had some cred.

JH You weren’t just another guy coming up from single-A.

John Right.

This was just the best summer of all of our lives. And when I heard Greg say that years later, it’s like, but you got to The Show! Mario Soto said it; Greg Riddoch said it. Paul Moskau said it. Larry Rothschild, I’m sure, would say it.

We loved each other madly. We still do. That camaraderie, just the majesty of the way we played. And then to have this wonderful leader who sort of gently cajoled us, shepherded us, to the heights we attained. I count myself as very, very blessed to have had that experience.

There was something in the water or something, and part of it’s [that] Eugene is a wonderful place, and part of it is that Civic Stadium was a wonderful place; but the players, the organization, and our manager was — it was a perfect storm, I guess.

JH Sure sounds that way!

John We weren’t the underdogs as we were the year before, but we were a brotherhood. I don’t recall any pettiness, jealousy, or ill-feelings. That we were so dominant and have maintained a degree of contact is because we loved each other that we were so successful. That’s Greg’s greatest legacy.

I’m incredibly grateful that I got the chance to play pro ball. I’m even more grateful that I got to play with some great guys on a couple of great teams. What a wonderful experience!