EARLY DAYS IN HAMMOND

You were a three-sport athlete in high school, with scholarship offers for football to play quarterback.

My senior year, we were undefeated state champs in football, and I was named first-team Parade magazine All-American quarterback, so I had all these scholarship offers – and I played basketball, too.

But when I was 7 or 8 years old, I started playing baseball, and I fell in love with Ernie  Banks. That’s who I wanted to be like, more than anything; I wanted to emulate him. So once the baseball season rolled around, and I had agreed to go to college on a football/baseball scholarship at Ball State, it made it easier playing the baseball season.

Banks. That’s who I wanted to be like, more than anything; I wanted to emulate him. So once the baseball season rolled around, and I had agreed to go to college on a football/baseball scholarship at Ball State, it made it easier playing the baseball season.

Then, when I got drafted, there was just no thinking about going to college.

You had offers from many larger schools. Why choose Ball State?

Most of the colleges that were recruiting me – and all of the Big Ten schools – said that if you played spring football, you couldn’t play baseball. You’re on a football scholarship, so you’re playing football in the spring.

But I got this letter from Ball State head coach Ray Louthen to come and visit the campus. He said, ‘we’re a small school, but I have something to show you.’ So we drove over to Muncie [Indiana].

Right away, he said, ‘you are going to be my starting quarterback, and the starting shortstop.’ I said, ‘how do you figure that?’ He said, ‘I’m also the baseball coach. I have other people to handle spring football. You’re my shortstop, and you’re my quarterback. How does that sound?’

I said, ‘where do I sign?’

So I signed to go there, and two or three weeks later, the amateur draft came, and the Reds picked me #2. My Dad said, ‘what do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘I’m going to play pro ball. I’m living this dream.’

But you didn’t have much negotiating leverage; you didn’t have an agent.

The day after the draft, cross-checker Tony Robello and scout Dale McReynolds are in my living room with my Mom and Dad. Tony lays this contract out there, and it wasn’t worth much. My Dad said, ‘wait a minute. This isn’t much money. Let me show you something.’

So he got my scrapbooks that my Mom had kept for my whole amateur career, and leafed through them, bragging about me. ‘He’s an All-American quarterback. He can go anywhere he wants to college.’ Yada, yada, yada.

Tony lets my Dad finish, and he says, ‘Mr. and Mrs. Chaney, you should be proud of your son. He’s quite an athlete. But if he doesn’t sign this contract tonight, he’s going to pass up the chance to play in the big leagues.’

My Dad and I go into the kitchen, which was only a few steps away. And he said, ‘what are you going to do?’ I said, ‘Dad, I’m going to play baseball. I’m going to get out of here, and I’m going to play baseball.’

The next morning at 7, Dale McReynolds was back at the house, putting me on an airplane.

PRO BALL

You went to Sioux Falls and hit .212 in 98 games in 1966.

Something like that; I showed some signs, I guess. Stole a couple bases, made a couple plays, looked good in batting practice, hit a few home runs — that kind of thing. They liked me. I got to go to big-league camp the next year; that was quite a thrill.

Uncle Sam had plans for you after that season, though. You only played part of a season in 1967.

I had to spend the 1967 season in the Army. I was in the Army Reserves, but I got activated, so my first full year was 1968.

What did your time in the service do for you – physically, mentally?

It made a man out of me; the Army will do that. And it did put weight on me. A lot of discipline, too. I was one of those guys who had to lose about 15 pounds when I came out of the Army – to get back to shortstop weight. So I went back down to 195.

And 1968 was a key year in your career at AA Nashville.

I still only hit .232, but Sparky [Anderson] moved me to second base. We led the league in double plays — me and Frank Duffy. We made the All-Star team, I hit 23 home runs and drove in 78. Sparky put me in the fourth position, and the next year I’m in the big leagues.

You struck out 159 times in 1968 – a big total for those days. Did anyone in the organization say anything to you about that?

The metrics weren’t even out there; I wasn’t even thinking about it. No one said anything. I guess they were looking at the potential.

THE REDS

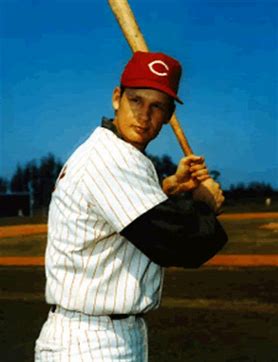

And in 1969, you made the big leagues with Cincinnati.

Woody Woodward was the starting shortstop. Dave Bristol took me to the big leagues, but he didn’t start me. I guess he wanted to bring me along slowly. I hit a couple of home runs in spring training, and I was still showing signs of a lot of power, but I’m 21 years old, sitting on the bench in the big leagues. How often do you see that anymore? Usually you’re playing in the minor leagues every day.

You hit your first major-league home run off Juan Marichal, September 7, 1970. That’s a pretty good notch to have in your belt.

Yes, but he beat us that game [The Reds lost 6-3, as Marichal pitched a complete-game 11-hitter (!)]. About 15 years ago, I saw him at a Major League Alumni dinner in New York, and I introduced myself to him. He didn’t remember me [laughs].

Eventually, you choked up on the bat and hit down on the ball. What brought you to that point?

I just knew I wasn’t going to be a power hitter. I saw a bat that Roberto Clemente used to use that didn’t have a knob on it, and I felt like I had more control over the swing. It was  a model M142, and I just started using that. I went back to the minors in 1971 for a while, and I used that bat down there and choked up about an inch and had a real good contact swing. I had a pretty good batting average in Indianapolis; I didn’t hit many home runs, but I hit enough that I got back to the big leagues.

a model M142, and I just started using that. I went back to the minors in 1971 for a while, and I used that bat down there and choked up about an inch and had a real good contact swing. I had a pretty good batting average in Indianapolis; I didn’t hit many home runs, but I hit enough that I got back to the big leagues.

You hit .277 in AAA in 1971. But after a couple of years in the big leagues, and playing in a World Series, wasn’t being back in the minors a big letdown?

You gotta be real careful: if you don’t play well when you’ve been sent down – especially after two years in the big leagues – you can stay down there forever.

Vern Rapp was my manager down there. He called me into his office and said, ‘look, I know this is tough on you. But I don’t care what you do, you’re playing every day for me. Even if you’re 0-4, 0-8, 0-16, I want you to know that you are playing every day.’ And I did.

He made me feel like that’s how I could get back to the big leagues. He would give me every chance to do it, and so I’m glad he did.

Darrel did make it back to the big leagues in 1972, platooning at shortstop with Dave Concepcion. The Reds won the Western Division and faced Pittsburgh in the playoffs.

In the 1972 playoffs against Pittsburgh, the Reds trailed 3-2 going to the bottom of the ninth inning. Johnny Bench hit an opposite-field home run off Dave Giusti to tie the game. With one out, George Foster was on third base with the pennant-winning run. And you came to the plate, ready to win the game. How did you feel?

In the on-deck circle, I knew I was going to win the game. I really did. I could hit Bob Moose [who relieved Giusti] pretty good. I felt real comfortable up there. I could see the ball good. And I had no doubt in my mind: ‘I’m gonna be a doggone hero. I’m going to go down in the Cincinnati laurels as driving in the winning run in the playoffs.’

But you popped up to short left field for the second out. What were your emotions?

I just missed the pitch. It was right there. I got under it.

I thought I was going to win the game. Maybe I went up there with too much confidence. I don’t know if you can do that or not. A guy like me, I was platooning with Davey, and I was trying to make every doggone at-bat count. I had a whole career ahead of me. I wanted to be somebody. I wanted to be the star all the time, like everybody else was on the Great Eight [nickname for the Reds’ starting lineup].

I took a good swing at it. I thought I was right on it. And I popped it up. And I was so mad.

But the game was not over. With two out, there was a distinct possibility of extra innings.

I had my glove sitting on the top step of the dugout. My hat was on top of the glove. I came back in – now it’s first-and-third and two out – and I kicked my glove. It goes into the drain in the dugout, and my hat flies into the seats.

Right away, my hat comes back out of the stands. Whoever got it was so mad at me, they didn’t want it, I suppose.

And I was so mad – I’m down there picking up my glove and my hat, and I’m cussing at myself, and I didn’t even see the wild pitch.

[Hal McRae followed Chaney to the plate, and with the count 1-1, Moose threw a wild pitch.  George Foster scored the pennant-winning run].

George Foster scored the pennant-winning run].

What were your feelings after the wild pitch?

I turned around and saw everybody jumping up and down. So I went in there and celebrated, but it took me a while to get over that. We were National League Champions, but I was [angry] at myself — gosh, for a couple of days there – until the World Series started.

Did you feel that you got off the hook a little bit?

I was so relieved. There wasn’t anyone in that clubhouse who celebrated any harder than me. The pain actually went away, really, when the World series started, because I got to start against the righthanders early in the World Series.

I had been thinking ‘Sparky just may go ahead with Davey, right here.’ But he didn’t do that until the seventh game.

What would my career have been like if I had been the hero in that game? What if I had hit a three-run home run to win it? What if, what if, what if — you know?

Speaking of that: What if there had been extra innings? Jack Billingham has said that he was warming up in the bullpen, and he was “scared to death” of what might happen.

One thing I had no problem with was going back out there on defense after I made a bad out. I knew my strength was to catch the ball and throw guys out. I knew that was one of the reasons why I was in the big leagues. I knew that’s one of the reasons why Sparky was playing me.

So I was ready to go back out there, as mad as I was. You know, a lot of times when you’re mad at yourself like that, you become a pretty good player. How do you lose control playing defense? You’re mad, and you go harder after a ball that might have been a base hit – you catch one that could have been a hit, two feet farther or something. So that was not going to be a problem with me.

You were a platoon player that season, but things changed in 1973.

In 1973, Sparky gave Davey the job, but he broke his ankle the middle of the season. I played the rest of the year and in the playoffs, and we lost to the Mets. Then Davey came back from his injury in 1974, and he got the job back. The rest is history.

Darrel hit his only major-league grand slam in 1974. The story is here.

How difficult was it for you in those 1974 and 1975 years? Sparky told you that you had a role, but you were used to being a starter, and you were anxious to play. How tough was that adjustment?

It wasn’t bad; I wasn’t by myself. There were 16 other guys who weren’t playing at any one time, and about six of them were backup outfielders and backup infielders. We had a good rapport with one another; we understood our jobs, and we helped each other with the ups-and-downs of sitting on the bench.

And that’s one of the reasons why you win championships.

It isn’t because everyone can play the game so darn good; it’s because everyone can get along and help each other out. You have 25 players from 25 different parts of the world, trying to win a world championship. It’s really a neat thing when everyone can get along and spend the whole season together for that one common goal.

Was that more of a factor in 1975 – when the Reds won the World Series — than in other years?

Pete Rose called a meeting when we got to the 1975 Series and he said, ‘Look, boys, we’ve been to the playoffs three times, and two World Series, and we haven’t won one yet. We have to change our goal. We have to come in here and not be happy we are in the playoffs or World Series; we gotta win one.’

I think that made everyone refocus: understand your place on this team, and play well. And that’s what we did.

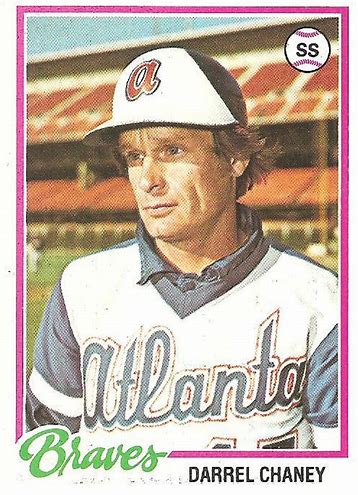

THE BRAVES

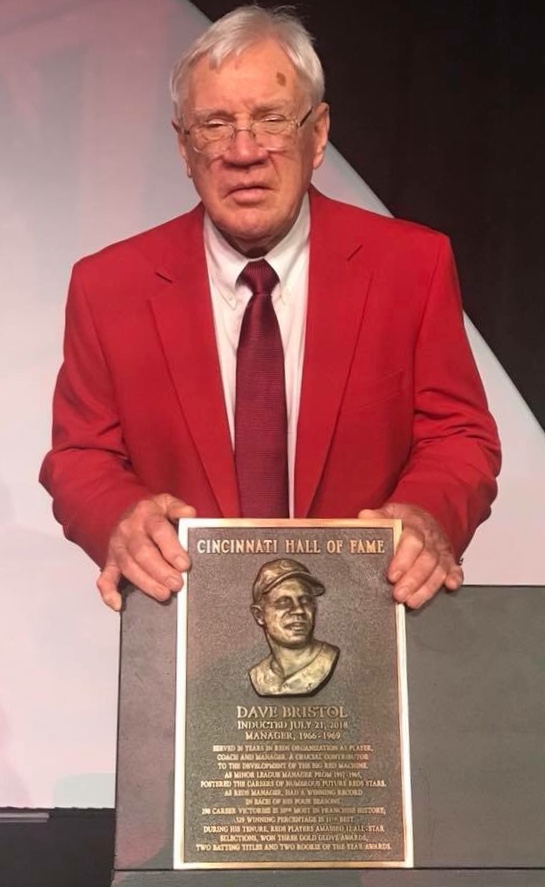

Then you get a big break – Dave Bristol wanted you on the Braves, and he traded Mike Lum for you after the 1975 season.

I got a chance to play every day, and Bristol saw enough of me to trade for me and let me play. We didn’t have a very good team, but we tried [laughs]. I got to play quite a bit, and I had a pretty decent year, for hitting eighth on a last-place team. Then they got a rookie phenom, and I had to back him up for a couple of years.

Speaking of Dave Bristol, you recently visited Cincinnati to see Dave get inducted into the Reds Hall of Fame.

He’s one of the more dedicated baseball men I’ve ever met. He’s 85 years old. He’s worked his tail off in baseball. What he did with the Reds had long been forgotten.

He took me to the big leagues, and then he traded for me. I love the guy. I love his family.

On April 10, 1978, you hit a two-run walkoff home run with two out in the ninth inning for Bobby Cox’s first win as a manager.

It was in the days when Bobby first started managing the club, and we weren’t very good. I wasn’t playing much. We were losing to San Diego, and he threw me in there to pinch-hit, and Bob Shirley was the pitcher. I was hitting right-handed – one of only two times I pinch-hit right-handed. Shirley grooved one, and I hit it over the left-centerfield wall. Probably got 1,500 fans excited – I don’t think there were very many in the stands that game [paid attendance was 2,056]. It was a school night in April, and we were bad, so they didn’t pack ’em in back then.

You were a backup for three years with Braves. Was that tough, as you headed toward 30 and had been around a bit?

It was so bad sitting on the bench in Atlanta, because I was backing up guys that I knew I was better than. It was very difficult to sit on the bench for a losing team, compared to sitting on the bench for a potential world champion — I can assure you of that. You play with some guys who have the attitude, ‘I just want the season to end.’ So those were tough days.

You even got into a game as a catcher for 1/3 of an inning?

We had a game in New York – the completion of a suspended game – we had a catcher go on the disabled list; one catcher got pinch-hit for, and we ended up with nobody to catch to finish the suspended game. Bobby Cox said, ‘we need somebody to catch a couple innings.’

For most of my career, one of the things I did to stay busy was to warm up pitchers. I’d go down to the bullpen and warm them up, or catch them if they were doing side-sessions, just to stay busy and have something to do. So when Bobby asked, and there was no one jumping up and down to do it, I said, ‘I’ll catch,’ so I put the gear on and caught BP before the game. Gene Garber was in the game for us, and he and I talked about it. He said, ‘just do the best you can.’ I think he walked a guy, we got one out, then someone hit a double and we lost the ballgame.

It was another thing I could put on my résumé, in case I ever got traded again [laughs]. ‘Hey, I can catch too, as your emergency catcher.’

For much of your career, you were a late-inning defensive replacement. That’s been called “the toughest job in baseball.” Is that an underrated skill?

Oh no. It’s not. Maybe today, the utility players get more credit, but for a guy like me –

I’ll tell you when it was really tough: when we would go out to Montreal or San Francisco, in those godawful cold conditions. You’d go in there in the eighth inning, and you’re paid to catch ground balls, but you couldn’t get loose. You’re sitting there for seven innings in the dugout, and you’re freezing. A lot of times, I couldn’t feel the tips of my fingers.

In San Francisco, we were in the third-base dugout and you had to go all the way to the right-field corner to get to the clubhouse to warm up. But it was what it was, and you tried to do the best that you could.

You had no warmup; no prep; and the game was on the line.

And if you got an at-bat, you were against the other team’s best relievers — Gossage and all those guys. Sparky once said, ‘I don’t care if he gets a hit; he’s in there for his glove.’

When you play at that level, and especially on a championship team, one of the mindsets that you have to have is, even if you are the 25th-best player on a 25-man team, you have to think that you have a chance to do something to contribute to the victory. So you had to have that confidence in the back of your mind.

You were released after the 1979 season, and you thought you could still play, but you never got an opportunity.

I figured, after 11 years in the big leagues, I hadn’t really known my son yet, and I knew one of these days I would have to go to work. I had a couple of offers with the Mets and the Pirates in spring training, but they were conditional contracts, and I said, ‘I have 11 years in the big leagues. I don’t need any conditions. Either you want me to be on your big-league club, or not.’

So I went to work.

AFTER BASEBALL

You were in broadcasting, as well as private business?

I worked in real-estate for a year, then Ted Turner bought the Braves, and had me come on as a broadcaster. Al Michaels got me into the Columbia School of Broadcasting when I was in Cincinnati, so I got a third-class operator’s license, and used that for a couple years with the Braves, thinking I would have some credentials, but I got fired from that job too. So I went back to work.

In recent years, you have been primarily a motivational speaker.

Yes, and it has been very rewarding. [see more here.]

Darrel coauthored the book, Welcome to the Big Leagues: Every Man’s Journey to Significance with Dan Hettinger. In the Foreword, he says

I’ve come to realize in a deeper way that, even though I was not the most-famous baseball player, my career and my life mattered … I was significant for who I was. Now I want to be an encourager for those who know me and hear me speak or read about my life. I want others to discover their God-given significance.

When you look back on your time in baseball, what is your career summary?

I had an opportunity to do something that millions of young men would have loved to have done. Then to realize that I had an opportunity, by being a major-league baseball player, to have a platform to have an impact on other people’s lives — even my own grandchildren — that is something I will be thankful for, for the rest of my life.

What’s in the future for Darrel Chaney? More speaking engagements?

As long as my health stays good, and the book is still out there, I need expense money and a little fee to [speak], but I plan to keep doing it.

Please visit darrelchaney.com to book Darrel as a speaker, and to buy Welcome to the Big Leagues.