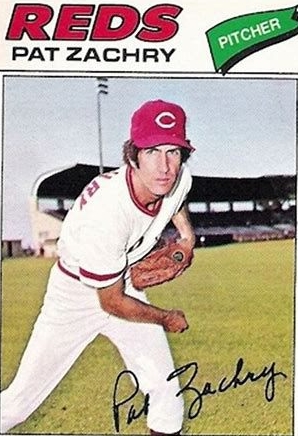

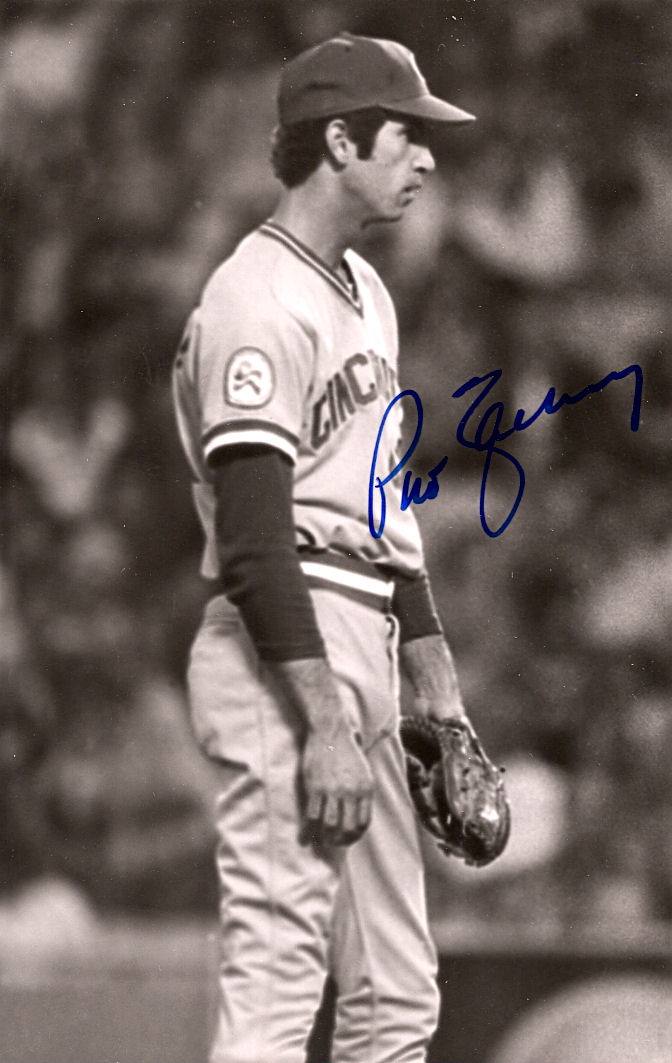

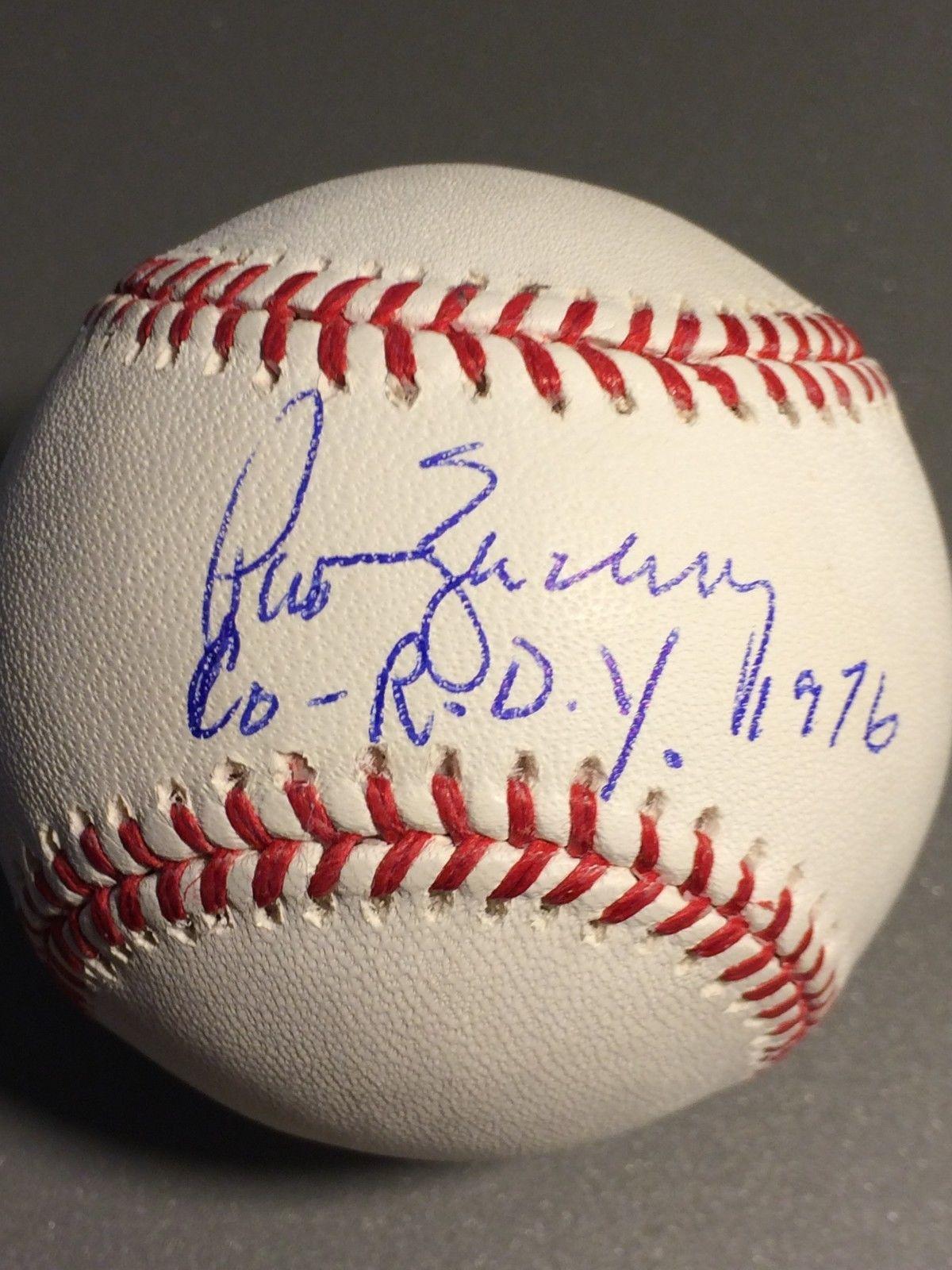

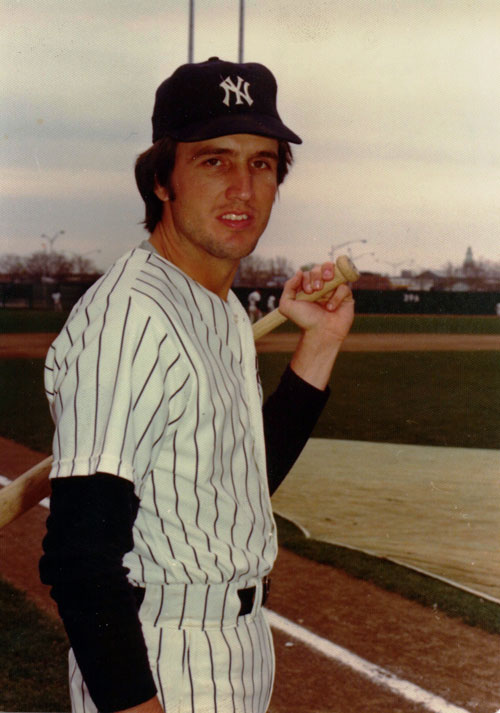

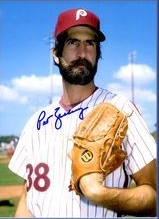

Pat Zachry was a 19th-round draft choice of the Reds who finally made the big-league club  in 1976. He responded by going 14-7 and was co-Rookie of the Year (with San Diego’s Butch Metzger) as the Reds won the World Series. The Reds won the National League West by ten games, and Zachry beat the second-place Dodgers five times. He was traded to the Mets in 1977 as part of the Tom Seaver deal, and he pitched for the Dodgers and Phillies in a 10-year major-league career.

in 1976. He responded by going 14-7 and was co-Rookie of the Year (with San Diego’s Butch Metzger) as the Reds won the World Series. The Reds won the National League West by ten games, and Zachry beat the second-place Dodgers five times. He was traded to the Mets in 1977 as part of the Tom Seaver deal, and he pitched for the Dodgers and Phillies in a 10-year major-league career.

Note: Pat was a fiery competitor when he pitched — one of the reasons I liked him so much — and that’s reflected when he talks about his career. He is blunt and direct, and his language can get rather salty (shocking revelation: ballplayers curse!). But to sanitize that is to take away from the “flavor” of who Pat is, so there are a few NSFW passages here.

Were you always a pitcher?

No, I played first base as a beginning position and pitched. Then when I was 9, I was catcher and shortstop and pitcher – I just always was a pitcher or a catcher, simply because of my arm.

It sounds like you learned how to pitch by pitching.

I always thought experience was the best teacher. Sometimes hard lessons are the best.

You better know what you have when you step out on the hill of thrills.

You were more of a ‘feel’ guy? ‘Let’s see what I have today,’ and go from there?

Yes, sir. You better know what you have when you step out on the hill of thrills, and the only way you can do that is to take what you’ve got down in the bullpen and apply that to what you go out there with.

Did it make a difference to you whether it was the game mound or the bullpen?

Well, by and large you knew what you had each time you go out. But whether or not you have your real good location, sometimes you just gotta go out there and work. Can’t throw a no-hitter every day. Sometimes it’s a genuine struggle just to get by.

So the hitters will tell you what you have that day?

Yes, either the hitters or the fielders [laughs]. When you see all the married guys start running for the dugout …

Was your career a case of a guy who was a 19th-round pick not getting as good of a shot as others who were higher up?

No, I wouldn’t say that. I will say, though, that in the minors, the guys who were high bonus picks and got bonus money got more of a shot than guys who didn’t. That was an occurrence, but if you earned your way, the proof was in the pudding, and they would take a look at you.

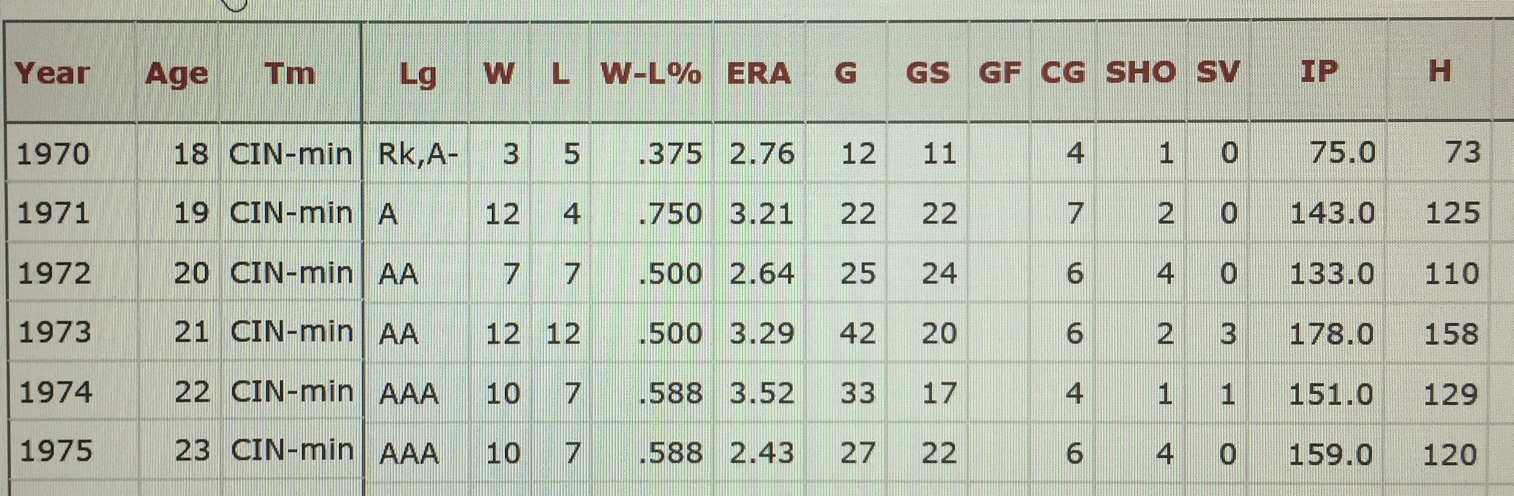

It’s just amazing to me that it took you so long to get a real shot with the big-league club, considering the numbers that you put up.

I found an old clipping recently that had me rolling in the aisles. It was from a 1975 Sports Illustrated. I’m in the article from AAA baseball, because Cincinnati was the only team in organized ball that didn’t let their minor-leaguers have designated hitters. As a result, I was 0-for-April, May, June, July, and now they come down the first week of August to write the article. It just so happens, [Reds GM] Bob Howsam comes down to take a look at people he needs to pull up to help the big club.

Pat Darcy and I were roommates, and we were both having good years. And I was pitching my ass off. I get my first base hit that night, and I’m going around first base, and I blow out a quad muscle and just barely make it back to first base.

As luck would have it, they call up Pat, which was a good thing for him; then I had the good fortune to get about five more base hits. And every time I did, I’d blow that thing out. Or if someone knew about it beforehand, they would try to bunt on me, and I’d blow it out trying to make a play on a ball. But I lasted through the season.

But it was just one of those quirks of fate: Howsam comes down to look at somebody, and I blow up. I get my first frickin’ base hit, and I blow up going around first base!

But Darcy, they called his poor ass up, and his arm was so worn out – he said ‘hey, I was hurt, and I was dying.’ But I knew Pat. He wasn’t going to say anything. ‘No, I’m sorry, Sparky [Anderson, Reds manager], I can’t take it.’ And I guarantee, if you asked him right now, ‘was it killing you?’ he’d say, ‘nah, it was fine.’ That’s just the way he was.

You got passed up for big-league promotion, despite having several good seasons. I know they had a decent major-league staff, but still …

Well, they were winning pennants with the guys they had, so you don’t want to screw up a good thing.

I thought maybe you’d at least get called up by 1974 or so.

Well, Sparky didn’t like kids. He didn’t like youngsters.

In 1973, did they try to make you a swing man?

Oh, boy! In 1973, I was lucky I didn’t blow my brains out. I’d had hernia surgery and got off to a real slow start: good game, bad game. So the manager puts me in the bullpen.

Sherbrooke was a farm team for the Pirates. Three games in a row, back-to-back-to-back nights, I gave up a game-winning home run in the 10th, 11th, and 12th innings.

I had just received a glove contract from MacGregor, and I just got a bright red kangaroo leather pitching glove. After the third home run, I took that thing and threw it probably 300 feet, right into the stands. The last thing I saw of it, some Canadian kid had caught it on the fly and was haulin’ ass through the turnstiles. That was as low as I have ever been in baseball.

What was the solution?

Jim Snyder, the manager, bless his heart, gave me a start a few days later against the same bunch. And I think in eight innings I had 15 strikeouts. I think we lost 1-0 in ten innings.

But it was definitely a different feeling out of their bench. They weren’t hootin’ and hollerin’ or anything that night. Because mostly – and I wish [Joaquin] Andjuar was still alive to tell you — just about every pitch was a fastball. I think I threw one breaking ball, and Mitchell Page had a bloop single between short and second; that was the only one.

Were you throwing two-seamers, and relying on movement to do the job?

No, I was throwing the shit out of it [laughs].

I was in a zone, I was mad, and just wanted to get some back that night. The catcher, Oscar DelBusto, had come over from the Orioles, and he wasn’t even putting down a sign; he was just holding his mitt right there: boom-boom-boom.

It was fun. I get goosebumps now, just thinking about it.

Just rock-and-fire?

Yeah. As soon as a guy stepped in and tapped the plate, ‘here it comes!’ It was really nice.

You have said that coaches Ron Plaza and Scott Breeden helped you out when you were young.

Yes, they did. Plaza was my first manager, and of course Scotty was a pitching coach. He taught me how to throw a changeup, which was so valuable to me later on.

Plaza just instilled professionalism. When you step out on the field, you’re taking their money and you’re wearing their uniform, so you better be in sync with what they have in mind for you. And get out there and put on a good show.

Plaza’s style seemed to polarize people’s opinions of him.

Well, I guess about the second week that I was at Bradenton, right out of high school, they took me out of the bullpen, and they liked how I threw. I threw pretty hard, so they made me a starter. And about the second game I pitched, I gave up a home run to a kid on an 0-2 count.

When I got to the dugout steps, Plaza was ripping me up one side and down the other. I didn’t know what he was talking about: ‘what do you mean, 0-2 count?’ I thought, what the heck, you just go after ’em and try to strike ’em out. I missed location, and it went down the middle of the plate, and the guy hit it out.

So outside of calling me a dirty bastard, he just lit me up one side and down the other. And by the time he was finished, I was so mad that when I sat down, there was sawdust coming out of my fingernails. Breeden was a fairly good-sized guy, and he just kind of sat over and left me alone.

Someone was going to get their rear end tore up if they got in my face again.

It went OK, though, and about two weeks later I did it again, and Plaza just started laughing. He just kind of threw his hands at me: ‘you dumbass!’

So I guarantee you, the next time, the guy went down on his ass.

That will send a message.

Well, they told me, ‘if you’re afraid to hit ’em, throw one at their knees. They’ll move if you throw one at their knees.’ They don’t like that at all.

Sparky pushed you to pitch more aggressively.

Not so much Sparky as [pitching coach Larry] Shepard, Bench, [Bill] Plummer — good Lord, look out for the guy who tried to come after you with Plummer there! And Bench was the same way. John was built like a fireplug,

You were taught to pitch low—keep the ball around the knees, and you wouldn’t have as many problems. Then when you wanted to come up high, it was a surprise.

When you were drafted, were you mainly a fastball guy?

I always had a decent slider, and the changeup was something that I had as I got to AAA. When I hurt that leg muscle, it was a good thing I had the changeup, and I had two really good catchers: Don Werner and Sonny Ruberto — and even Hal King had come down there. Cincinnati had great catchers.

I got into a spring-training situation where they let me go over a couple of times and throw batting practice just to Pete [Rose] and Joe Morgan, Ken Griffey, and Danny Driessen and Champ Summers, and just play with them – play around throwing the changeup.

Pete and Joe were aggressive; if they laid back, sneak it by them; throw something else, but they would be sitting on something, and you throw them the changeup, and it was fun to watch. It was a lot of fun to play with it.

What kind of changeup?

Straight change with the last three fingers around the ball – thumb and index finger

together.

So you got some tailing action on the pitch?

Oh sure, and a lot of times it would just kind of fall off the table if you did it right. I didn’t do it on purpose, but my arm would sort of turn inside, almost like a screwball. I got some interesting pictures that will bear that out, and a scar on my elbow from ulna nerve surgery from sliders and probably some other stuff.

I didn’t try to throw that way – it just happened.

You finally made the Reds in 1976, and you began the season in the bullpen.

I had no idea what they had in mind for me. I came in a few times in relief; I remember once, just for a couple of outs. It didn’t happen too often, then maybe two or three weeks into the season, I was in the rotation.

You beat the Dodgers five times in 1976, then lost the last game against them 2-1. What was it that worked so well for you against the Dodgers?

I guess maybe it was just being new. And Cey and Russell and Garvey and Yeager and Baker didn’t like sliders.

And they were all really aggressive – did you use that against them?

Yes, sir. And I’m sure John [Bench] had something to do with that, calling the games back there.

Wouldn’t they have figured you out after two or three times?

Don’t get me lyin’. I don’t know what it was. Apparently they had me figured out by the next year, because they beat the hell out of me a few times.

You had a great rookie year, and you pitched well in the playoffs and World Series. Was 1976 a whirlwind, and did it live up to your expectations?

What’s the expression? A gigantic letdown.

I didn’t pitch well in either [postseason] game, and that upset me. I wanted to pitch  better. I gave up a home run to Greg Luzinski — my God, he hit it so far—he almost hit it out of the ballpark. The only good thing about it was it was one row farther back than the one I gave up to Mike Schmidt during the season.

better. I gave up a home run to Greg Luzinski — my God, he hit it so far—he almost hit it out of the ballpark. The only good thing about it was it was one row farther back than the one I gave up to Mike Schmidt during the season.

The first time I faced Schmitty, I struck him out – blew him away on three pitches. The next time, later in the year, he hit one up there so far … [laughs]

You said you were disappointed in how you pitched in the postseason, but I remember Billy Martin saying you were the best pitcher on the Reds’ staff.

Well, there again, Jim Mason hit a home run off me. He hit one the next gosh-dang year, too. He pinch-hit off me in Montreal, and hit another one, the son-of-a-gun!

too. He pinch-hit off me in Montreal, and hit another one, the son-of-a-gun!

Were they on changeups?

I probably threw him a fastball down the middle.

If I ever run into him, I’m gonna shoot him in the foot. He liked me, I can tell you that.

He had a ‘cousin’ there, didn’t he?

I don’t know, but I’m sure the next time he knows where I am, he’ll send me dinner or something.

But you were still disappointed in how you pitched?

Well, we had to come back in the Philly game, and in the Yankee game the payback for me there was, I had my family there. And to have my Mom and Dad, especially, to see all that was very, very rewarding.

Some guy was silly enough to accidentally bump my mother in the head, and my sister was going to whip his ass, right there in the stands. You gotta remember, she was eight years older than me.

In December 1976, first-baseman Tony Pérez was traded to Montreal (with relief pitcher Will McEnaney) for pitchers Woodie Fryman and Dale Murray. The trade was a disaster for the Reds; they started poorly in 1977 and never recovered. This trade is widely pointed to as the beginning of the end for The Big Red Machine, and that its effect on the team was huge – from the first day of spring training.

Did the Pérez trade make as big a difference as it has been reported? Or was that overplayed as a reason for the club’s poor start in 1977?

Looking back on that, one of the things – and I’m hoping that I recall the mood correctly – was, ‘my gosh, if they do this with a guy who has been here for – what, 15 years?—and he has done what he has and put up the numbers that he did, and they get rid of him like he’s nothing.’ The only ones worth a darn would be John or Pete—that was it. They were the only untouchables on the team. Nobody else even had a chance.

At the end of 1976 you had hernia surgery and elbow problems. Did that hurt you at the start of the 1977 season?

Yeah.

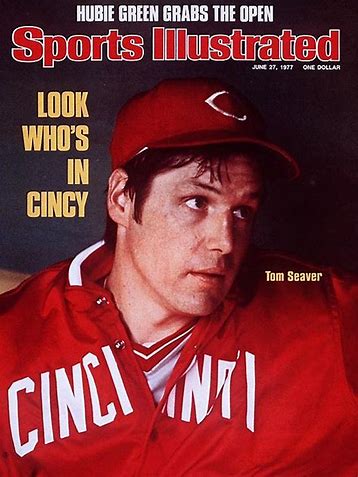

What in the world was going on? The whole pitching staff fell apart in early 1977. Then came the big trade June 15.

I don’t know what was going on in their thinking. They wanted to get Tom Seaver.

I was three days from getting married and having a reception at Pete’s house. They announced the trade, and I’d had the hernia surgery and was off to a slow start [2-6/5.76]. And they traded me.

I came walking out of the clubhouse that night and my wife said, ‘did you just get traded?’ And I said, ‘yeah. You get your car shipped back to Waco, and have mine shipped to New York. I’ll be back in three days and we’ll get married, and we’ll carry on from there.’

So this happens, and I come back in a couple of days and we get married, with a justice of the peace. Have to get all the gifts and everything shipped back.

She meets us in Chicago a week later, where they put us in the honeymoon suite with a big old bottle of champagne, flowers – really did it nice, and she meets me in New York, and we went to live, right down the street from where Son of Sam was shooting people, as it turns out.

I got my sports car traded in and got us a Cadillac in the offseason. We had the car about a month and somebody stole from out in front of the house one night.

You were 2-6 and 5.76 at the time of the trade.

Wouldn’t be surprised; I was pretty terrible.

It’s been written that Rawly Eastwick was originally in that deal, and you were subbed in after he balked at the trade.

I think Rawly said that even if they gave him the Empire State Building, he wasn’t going to New York. I had no refusal right or any of that in my contract, so: see ya later.

Did it catch you completely off guard?

Totally. We were going to get married! The worst part was that Mr. Howsam never came in and said ‘thank you’ or any of that. They left that to that awful SOB Chief Bender to do that stuff. Him and [assistant GM] Dick Wagner. What a couple of turdheads.

They always seemed to undervalue pitchers.

It was like you were just a piece of meat. Look what they did to Jim Merritt: first time someone won 20 games around there since Jim Maloney, and they completely washed him up. And Gary Nolan had to fight for his life every year, and he was always winning at least 15.

I’ve talked to Jim Maloney and Gary Nolan about that, and they both were told they couldn’t pitch with pain; they had no pain tolerance.

I’ll tell you, when that thing is bothering you in the elbow or in the shoulder … to have one of those guys tell you that? Goodness gracious! You need to slap ’em.

It’s terrible to be treated that way.

Well, look at who they used to have [in the minors] for trainers. There wasn’t anybody who was a certified trainer. The year that I signed, our trainer down in Bradenton was a guy from Oklahoma with one eye; he had a patch over one eye. His name was Jimmy Bell. He was a good guy, I guess, but he was not a certified trainer.

For anything that happened, he’d have to go get out his medical encyclopedia that was about as thick as a TV set is wide, and he would look at all these things – damn near out on the field sometimes.

I remember passing out on the mound the day before I got sent up to Sioux Falls, and he was looking through his medical guide on what to do. Instead of doing something to get my body temperature down, he was looking through his [effing] medical guide over there. I’m just thinking, ‘Jesus Mama, come and get me!’

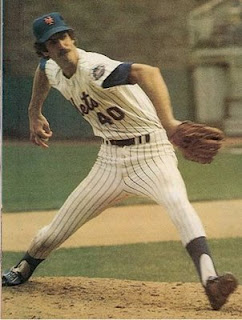

You were able to turn things around for the last part of 1977 after you went to the Mets. Was it a matter of getting healthy?

Yes, it was. I went to Puerto Rico that winter and had a good winter season. Got off to a good start in 1978; then, of course, there was the thing where I kicked at the helmet and missed it and broke my foot.

July 24, 1978, the Reds played the Mets at Shea Stadium. Zachry was the starting pitcher, and Pete Rose had a 36-game hitting streak – one short of the National League record. In the seventh inning, Rose singled to left field. An angry Zachry was removed from the game four batters later. As he left the field, he tried to kick a batting helmet. He missed the helmet, kicked a step in the dugout instead, and broke his foot. He missed the remainder of the season.

Were you angry about the base hit, or the situation?

No, I wanted to stop him. I really did. But you get struck by ‘terminal dumbass.’

That cost me the rest of that year, then I got off to a bad start in 1979 with my elbow, and had to have surgery on it. Cost me the better part of two seasons.

Was that from sliders?

No, the ulna neve got out of whack in there, and I was trying to come back, and I might have hurried it a little bit. I think it was a question of trying to come back – just getting it ready again.

You had a better year in 1980, but in the strike year [1981] things didn’t go so hot there, either.

[laughs] The strike year, I couldn’t have cared less about. The strike year was the best year of my life.

Really? How so?

We had just signed a five-year contract, went out to Connecticut and bought a house. We had a river and two ponds, and my wife was pregnant with our first child. He was born the first day of the strike.

My Mom and Dad were up there, with a travel trailer they brought up and parked in our driveway, it was just idyllic for the next 58 days – to be in that situation with him, to put him in his little papoose carrying pack and walk around in the forest with him — a really nice time. A nice, peaceful time.

But your time in New York was soon over, and you changed coasts.

In 1983, we got traded over to the Dodgers. We didn’t want to leave New York – we liked it. Every year we would have our anniversary dinner at the World Trade Center, and I can’t tell you how heartbreaking that was when we saw it go down.

My wife loved going into Manhattan. Remember Bruce Boisclair? His wife was a flight attendant with American Airlines, and she was from LA, but she and Sharron were best friends. They would go into the city all the time.

It seems you were pretty much done as a starter then. Were you viewed differently by the Dodgers?

We had five pretty good starters with the Dodgers, and five or six pretty good relievers, so the times [manager Tommy Lasorda] could use me were pretty few and far between.

He brought me in one time, and I don’t know if he was expecting me to fail or not, but it was a national TV game in Atlanta to decide who was going to be leading the division. Bases loaded, no outs. Gerald Perry, Bob Horner, and Dale Murphy were due up. It was ‘1-2-3, see you later.’

People were calling up after that, wondering why I didn’t get to pitch more. Hell, I don’t know. But it was fun to get it done on national TV, and get something positive.

You were traded to the Phillies in early 1985 for Al Oliver, but they released you in June, after only 10 appearances. That was the end of your major-league career.

What I was curious about was why, in 1985, they were even going to start the season. They knew they would have that strike [it lasted just two days] even before it happened. That was a bunch of crap. And to get released and not even be able to get back [to the big leagues], simply because I am making too much money? Nobody even wanted to deal.

So the handwriting was on the wall. Come home, open up a business, and go on down the road.

You got into coaching then too?

I got a batting-cage business built. Then the Dodgers called and asked if I wouldn’t mind being a pitching coach, so I went down to A ball at Vero Beach. Next year I was with Kevin Kennedy and Mike Sheehy in San Antonio.

We had six or seven kids off that staff make the major leagues. I was pretty happy with that. I know that only maybe two percent was my doing, but I’ll take that two percent.

John Wetteland was kind of a basket case. Good Lord, that kid could throw! But he might be one of those guys who would hit you in the ear, or he might be one who could throw a 12-6 curve ball that would make you shit your pants. He could throw some kind of stuff.

And Ramon Martinez, Pedro’s older brother, had a really good knee-high fastball and a knee-to-ankle changeup. Couldn’t hardly throw a breaking ball at all, but he could throw a changeup. Whew!

Was it a matter of trying to get them to harness all that good stuff that they had?

No, I was with them through AA, and they had Brent Strom for our AAA pitching coach, and I guess Wetteland went to the Yankees, Ramon went to the Dodgers major-league team, and I think he blew up a shoulder.

Brent Strom was not my sort of person, but that doesn’t make him good or bad as a pitching coach. I’m sure he was good at his job. He’s more technical at it than I am.

Some guys went through college to get where they are; I didn’t go to college and wasn’t ever going to get to college. I had to work at it, and come up the hard way. Not to say his [path] was any less difficult than mine; but he was certainly more of a cerebral person than I am about it.

And you pitched in the Senior League?

One year. One season, and it was done. Toward the end of it, Pat Putnam hit me on the  outside of my ankle and it broke in a barber-pole fashion. They were gonna cut my salary in half, and I told ’em hell no, I was fine. They put a splint on it and I pitched two more games.

outside of my ankle and it broke in a barber-pole fashion. They were gonna cut my salary in half, and I told ’em hell no, I was fine. They put a splint on it and I pitched two more games.

A spiral fracture? That’s a little strong for the Senior League, isn’t it?

Well, they were gonna cut my money! That money was keeping my family alive at the time. My wife was trying to get her second degree. She did that and became a principal, and the rest of that was history. She was Principal of the State twice.

I became a substitute teacher. I subbed for about ten years and retired from that, and things happened as they did two years ago.

On November 21, 2016, Sharron Zachry died in a one-car accident on I-35 near Ross, Texas, when the Zachrys’ truck left the road and rolled over.

I was driving down the road one minute, and I was looking at her, and thinking how, after 41 years of knowing her, she’s still as beautiful as the day I met her. The next thing I knew, we were laying on my side, and everything was all mashed in and mashed up, and they were trying to cut us out with the Jaws of Life.

She was a good woman.

After an awkward silence, I offered condolences; I didn’t know what else I could say that would help. Pat thanked me and then composed himself.

How is life for you now?

It’s 24/7 without the woman I love.

Boring. I can’t drive. I’ve got a golf cart where I can go right across the street to the golf course, and I’ve got a great view. I live in a facility – real nice people, but what can I tell you? It’s 24/7 without the woman I love.

What’s in the future?

Just being PawPaw. My son has four boys down in Austin. He’s one of the chief troubleshooters for Dell computers. And my daughter is a fifth- and sixth-grade teacher here in the school district where my wife taught. They have one girl.

I’m just gonna raise grandchildren, play a little golf, and wait out the days.

When you look back on your time in baseball, are you satisfied with how it all played out? Would have liked to have done more?

I wish I could have played longer, rather than nine years and change as an active player. I would like to have played about 15 years, if my body had held up.

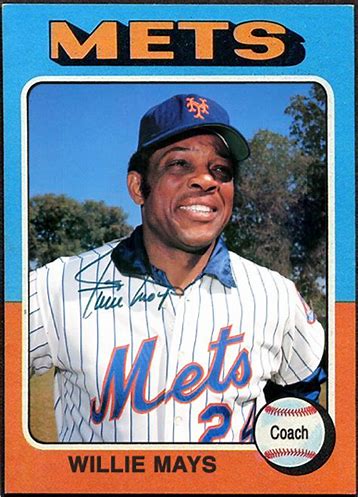

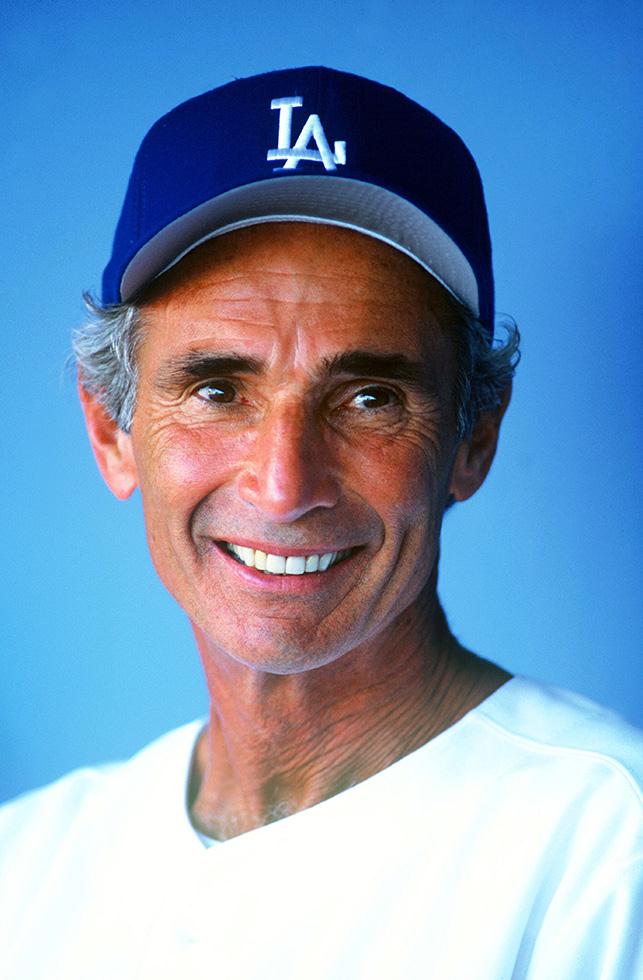

But I was fortunate enough to come along with instructors like Willie Mays and Sandy  Koufax. I lived in Willie’s house when I was rehabbing my foot in 1978 after I kicked the step. Willie gave us his house: ‘here, you don’t owe me rent – just take care of the phone bill.’

Koufax. I lived in Willie’s house when I was rehabbing my foot in 1978 after I kicked the step. Willie gave us his house: ‘here, you don’t owe me rent – just take care of the phone bill.’

Koufax, you could talk to him all day – all day. It didn’t make any difference who you were.

People like that who were nice enough to give back to me, I was the luckiest man in the world to be around those kinds of people.

You’re sort of conflicted in your feelings about Pete Rose, though?

Pete? I know he did wrong, and I haven’t made up my mind on his situation, but I love the guy. He was sure good to me. I just don’t know how I should feel. I know he did wrong, but I don’t know how I should feel. Pete, you know the rule going in frontwards, backwards, sideways — you know the rule. I can’t understand how you could be so cocky. Damn, Pete!

Is there anything else I can do for you?

I’ll shoot you my mailing address, and if you can send me a couple suitcases full of $100 bills, I’d appreciate it.

You know, I’m just a little bit short on that.

Postage stamps just ran out, huh?