George Sucarichi was signed by the Reds after a “showcase” in Tampa, Florida. He played a single season, split between Eugene and Billings. But he clearly relished his time in pro ball: “I only played one season, but I have a thousand stories,” he told me, “and I won’t hold anything back.”

He didn’t.

Here’s a look at George’s 1975 season, and life after baseball.

JH Were you always focused on being a baseball player? Did you play other sports?

GS When I went to high school, there was only basketball, football, and baseball. I played them all.

My senior year, I did not play basketball. My high-school baseball coach was a guy named Larry Grable. He had been a minor-league pitcher in the Cincinnati organization. And he told me, George, you keep playing baseball, and one day you’ll get a chance. I mean, he’s telling me that in high school, and he was a great coach. He was tough.

JH Were you signed right out of high school? Did you go to junior college?

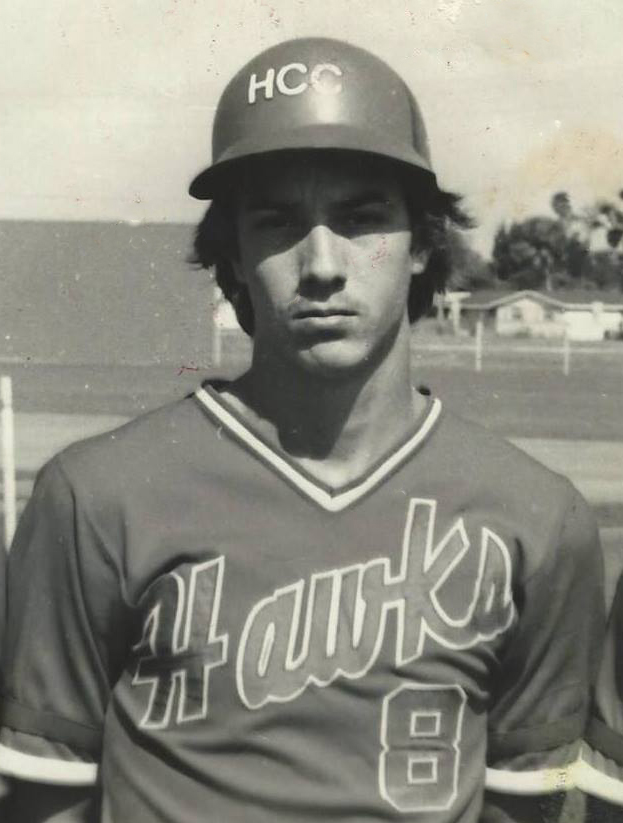

GS I was at Hillsborough Community College, which is right here in Tampa. I was playing at HCC and I got the call: Can you show up? And of course, yeah! What are you gonna say? No?

GS I was at Hillsborough Community College, which is right here in Tampa. I was playing at HCC and I got the call: Can you show up? And of course, yeah! What are you gonna say? No?

JH Did you know teams were interested in you, or was somebody bird-dogging you, or how did that work?

GS I mean, we’re not sure because the scouts would come around, but I don’t know that they talked to the coaches that often. Now, you’ll call the coach.

I did some scouting before my son was old enough to start playing, under a guy named Russ Bove, for what was then the Expos and became the Nationals.

But now the scout will call a head coach and say, coach, tell me about the kid. And how’s his grades? You know, they’re looking more at the character — the makeup of the kid.

Back then who gave a — it didn’t matter how flakey you were back then, if you could play. That was the order of the day. Can you play? But now they kind of dig into some of that information a lot more than they used to.

So I was not aware keenly aware of [being scouted]. I just remember getting a phone call, asking me to come out the following day.

JH Were you the classic guy who played short and hit third from Little League on up?

GS Well, kinda sorta. I started off playing outfield, and then my arm really developed — probably one of my best tools. So [then] I was a shortstop.

George was in for a big surprise when he went to what he thought was a tryout camp at the Tampa Tarpons’ ballpark.

GS When I went for my — nowadays, I call it a showcase; back then you just got a phone call and they’d say show up here. And they were going to hit you some fungos and they were going to time you in a 40, you would take some BP and so forth.

Well, I got a call. What I remember, they said, can you come out to the park on Sunday before the Tarpons are gonna play?

And I said, yes, sir!

Well, be there at this time.

Yes, sir. I’ll be there. Well, you don’t mind me asking you, who’s going to be in it?

Some other fellows.

Okay.

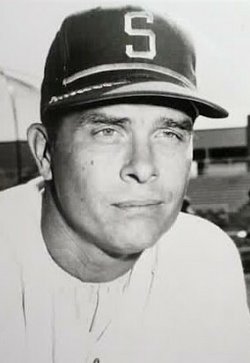

So I go out there on Sunday, my Dad’s with me, and I get there and I go to where the clubhouse is. And I’m asking around this time looking for this Ron Plaza fellow, you know? And so he’s there and he introduced himself and another guy, there was a Tarpons guy. So he’s going to bring him out too, and there was a scout there.

Plaza says, all right, let’s go out. And I’m looking around for the other guys. Where’s the other fellows? I’m thinking that I missed them, or maybe they’re already out there. Maybe they’re sitting in the dugout, waiting to see these other fellows. And we get out there on the field and there’s nobody there.

This is a solo showcase. Solo.

JH It’s not even a tryout camp. It’s a —

GS It’s my stage; that’s what it became.

And we went out, loosened up, timed me into 40, and it was all Plaza. And then I took fungos; he made me go left and right. Then I took BP. Hit-and-run, hit the ball to right field, told me what he wanted me to do: bunt here, do that, do this. So that was basically the workout.

Then we went inside, and they put this contraption on my head. You know, technology today, it’s nothing like back then. They put this thing over my head, and he would manipulate it with some type of little device. And then you had to tell him what you saw or didn’t see, or what moves or what didn’t move, so they could measure eyesight.

But it was all Ron Plaza. He was quite a character.

JH How were your dealings with him? People seem to either love him or hate him.

GS He was gruff, and he drank a lot. He worked hard. I mean, Ron had that signature gray T-shirt on, soaking wet — every day, all day. He was a hard worker. He’d throw BP. He was always on the move. He was always doing something. And he took it real serious, and he was an instructor. But he was kind of a no-nonsense guy. Definitely. I mean, that’s just how he was.

I was a real loose wire back then, to say the least.

JH How was your relationship with him?

GS Really, the only run-in I had with him was in winter ball. I was in St. Pete and we were playing a game and a kid pitcher threw at me, basically. Hit me in the side. And I was a real loose wire back then, to say the least. So I kind of walked out into the grass with the bat in my hand. And I started to lean toward the first-base line. I told him you ever do that again, I’m gonna beat you senseless with this bat. Because that’s just — that’s the way it works.

JH Yup!

GS You’re going to throw at me? Well, listen: you know, that’s your job. I’m going to do mine.

And Ron didn’t like that.

JH Wow!

GS He caught me after the game. He told everybody else to leave, but me to stay there. He told me if you ever do that again, if I ever see you do that again, you’ll never wear this uniform for the rest of your life; it will be your last day. And I didn’t understand that.

Because back then the game was mean; it was a mean game back then. You were supposed to go after people, and you better have an explanation if you didn’t go into second base. You  better take somebody out. You going into home? Better take somebody out.

better take somebody out. You going into home? Better take somebody out.

JH [smiling in agreement] Sure!

GS You’re turning a double play, and a guy comes in, why, you put [the throw] right in between his eyes.

JH Yup! Make them get down. All that stuff.

GS It was mean! I mean, that’s — it was expected.

JH Was he upset about the bat, or that you went —

GS Just my reaction; that I didn’t just flip the bat and run to first base. He just didn’t like the fact that I threatened this guy with a concussion. But you know, I didn’t like the fact that he told me he didn’t like it. It was extremely competitive and it was being — you weren’t supposed to play pansy with the other team.

You know, these guys [today], they don’t run to first base. They slide straight into the bag at second. Nobody wants to hurt anybody. And they’re all making so much money. You know, now it’s like, oh, well, I don’t want to go after anybody because geez, you know, might end their career. They won’t make more millions. I mean, I don’t understand that. The game has just softened down a lot. It really has. They’ve really, really softened the game.

Playing for the Emeralds

JH What about what about the time you spent in Eugene, and your relationship with Greg Riddoch?

GS I liked Greg. He was a good guy.

JH Is there anything that you can put your finger on about Greg? The overwhelming view is that he respected players. He wasn’t that much older than you guys, but he gave you room and let you play. And didn’t overmanage, but he could still run a game, and everyone knew who was in charge.

GS I liked playing for him. I just liked the person that he was — his personality.

He did not overmanage, and he had this very deft touch in how he would instruct or mentor. You never thought it was personal. He had that way about him where he could get his point across, but you you never took it personally. You never thought he was attacking you or belittling you in any way.

JH And he’s been compared to — the polar opposite of Ron Plaza.

GS Yeah, because Plaza was just this no-nonsense, gruff, I might smile, but probably not kind of guy. He acted like he was angry about something all the time. He just never acted like he was a happy person.

JH Some players say that he ruined guys; he was abusive. But Greg, people say he could straighten out a problem in your game, but you didn’t take it the wrong way.

GS Yeah. Not necessarily critical. And if he was, it was friendly; more instructive than it was critical. Plaza would just look at you and say, what the hell are you doing? He’d just condescend. Which I understand; I understand that style too. And it didn’t bother me at all.

There are players that are — there are players that doesn’t work with. Everything doesn’t just wash off everybody the same way.

JH No, I mean, a guy like Ron Oester has said that he was he was glad to have played under

Plaza, because he felt like he needed that and Plaza had to toughen him up. And —

GS [Oester] got caught with a corked bat once. I think he had a doctored bat.

JH Several other guys have said about Plaza, I love that guy. He supported me. He thought I could play, and he helped me out. Just don’t get on the bad side of him.

GS If you grew up with a real tough coach or a real tough Dad — somebody that pushed you and didn’t do it nicely, but you knew that they were still there for you, then typically, if you were wired that way, it wouldn’t bother you: he’s just being his dick self. But then you’d go out and have dinner or you’d have a nice conversation about something.

I’ve been that way. I’ve done that off and on in my life, many times.

Getting ready for the season

GS The weather in Eugene was always shitty.

JH Liquid sunshine?

GS You didn’t get a lot of sunshine; you just didn’t get it that often. At night, it was always a little bit dreary. It was a little bit cool.

I remember hardly anybody had a car. And I remember that we used to walk downtown – about five miles — we’d walk downtown. We’d walk all around downtown. Then we walked to the park. We’d take pregame: fungos, BP, and all that stuff. Then you play the game. Then you get out, you’d have to go walk. I used to go walk to this diner that was well past the apartment.

But I can remember back then that you could do this every day, all day, and never really get tired. That’s how good of shape we were in. I was never in that kind of shape in my entire life. There was just no end to the energy. I mean, you just never got tired. That was because spring training was pretty hard. I mean, they got you in shape in spring training.

JH A lot of running?

GS A lot of work, a lot of running. We’d do an hour of calisthenics in the morning, every morning. Doing stuff you never even didn’t even understand what it was for, until you woke up that second or third morning and you could barely move. And then you realize I got a lot more muscles, and I don’t even know where they are, or what they do, but I know right now they’re hurting very badly.

It took a week to get over that; to get through it. And there was a lot of running; whether it was just running for running’s sake, running bases, practice sliding, playing games, running situations. I mean, you were constantly running and on your feet.

Spring training would start at nine in the morning and get done around four. And that’s if they didn’t keep you afterward to work on something. This was every day, all day. And you got soup and crackers for lunch.

I was never in that kind of shape in my life. I can imagine in the military, it’s the same thing. They get you in that kind of shape.

JH You were in basic training!

GS That’s basically what spring training was, especially the first few weeks. You were going to be in shape, one way or another. I can remember doing that every day, just putting in miles and miles. Walk back to the apartment, watch a little TV, go to sleep.

JH I can’t see how you had time or energy to do anything else.

GS Never got tired. Legs never felt sore. I mean, you slept, you got up, you ate, and then off to downtown you went, and then you had to be at the park.

A close call on the road

GS Some of these towns, you were like big-leaguers to some of these women. So we’d go to these towns sometimes and there’d be girls in the stands and they’d kind of wave and look at you, you know: kind of pick you out. And they would try to catch you, because Greg was pretty commandant about the whole thing. So you had to sneak it, and he was pretty sharp. So you had to sneak it; you had to sneak it.

So the girls would kind of wait, hanging out somewhere between where we came out and the bus. And they’d sort of say, where are you staying? You know, where are you at? What’s your room?

So you you’d say, Oh, I’m down here at the Pilot Motel, room 202. And so before you say snap, crackle, pop, they show up.

So [Player X] and I scheduled these two chicks to come in. So the two girls show up, and we got them in the room. Nothing’s happened yet. They’re just in the room. We’re just kind of hanging out there on the two beds, a little TV going; Johnny Carson or something.

And all of a sudden, there’s a knock on the door.

JH Oh, holy sh–

GS Yeah! That’s right. Because back then, you got fined. And nobody was making any money. You know, they fine you 50 bucks, you wouldn’t eat for two days. So we scrambled.

I was like, oh my God! You know? And he knocked again: Hey, open the door, boys! It was Greg.

Oh God, it’s terrible.

I’m on the bed closest to the end of the room, near the wall. I take her and stuff her as far as I can under the bed — between the bed and the wall. And I kind of drooped the blankets over, you know, like I moved them or something, you know, to get up. [Player X] takes his girl into the bathroom and puts her in the shower.

JH [aghast] I mean, Jesus, it’s one of the most obvious places!

GS And he puts her in closest to the door. I think he left the shower curtain halfway open. So he takes this risk. She’s standing in the shower; the other one was on the floor. And I’m telling her: don’t breathe!

Then Greg walks in — he saunters in. Hey, [Player X]! Hey, Suke! How’s it going tonight? I mean, I’m laying on the bed in my underwear and T-shirt. Greg’s cool.

Watching a little Carson in here, you know? I mean, I’m trying to give my best Robert de Niro performance and laying there, and he’s stoic.

And he says, Hey, yeah, great. Walking around, his head’s on a swivel. He’s looking in between the beds. He looked through the bathroom door when he first walked in, and he’s just looking around — almost like he knew something was going on.

He comes, he walks down about halfway. And he kind of spun and looked at me, laying there, asked me a question or two. And she’s right there on the floor. He turns, he goes to walk back to the bathroom. Kind of sticks his head in – of course, the shower curtain’s half-open. And he says, okay, lights out, and leaves. I mean, Ooh, lucky, lucky, lucky.

So now we have to figure out how to get the girls out of the room.

JH [laughing] You built the boat in the basement, and you can’t get it out the door!

GS What do we do with them now?

So about two minutes later, somebody knocks on the door again and we’re thinking, stick them back where they were.

But it’s one of the guys: come out here, come out in the hall.

So I thought, yeah, Greg knows. He’s just going to walk us out there and walk in here and get the girls. He’s going to make us look like a bunch of —

We go out in the hall and there’s all kinds of people standing in the hallway. Greg’s standing there with [Player Y]. He says, boys, look what we got here! I don’t remember if he made the girl walk out and leave. He told [Player Y], say goodbye! They’re putting [Player Y] on the stage, on the platform, in front of everybody. He made a whole bunch of us come out of the rooms, so we could watch and we could share in the humiliation. So we’d all know: This is what it feels like if I catch you.

So he got [Player Y]. And we are standing out there. We still got two girls in the room!

JH What the hell do we do now?

GS So we waited and they stuck around for a little while and we got — super sleuth stuff. I Spy. And we open the door a little, look around the corner. Okay, come on, come, come on! And we shuffled them out, and they went down the hallway and we went back in the room, closed the door.

JH You got away with it?

GS We got away with it. Although we didn’t really get away with anything. The girls had just been kind of hanging out for a few minutes with us.

And when Greg walked into that room, my sphincter was puckered so tight! Oh, my God. And trying to be so cool: Hey Greg, how’s it going?

JH I imagine the old heart was pounding pretty good.

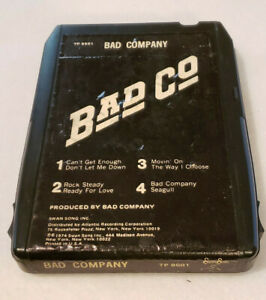

A one-tape bus

GS I do remember in Eugene — and I still listen to this music to this day — I remember we’d take  the bus rides, and we had one eight-track tape. And it was Bad Company’s Bad Company. And that tape would play over and over and over, for hours and hours and hours on the bus. I knew every note, every word, everything about every song on that tape.

the bus rides, and we had one eight-track tape. And it was Bad Company’s Bad Company. And that tape would play over and over and over, for hours and hours and hours on the bus. I knew every note, every word, everything about every song on that tape.

Every time I hear some of that music, it puts me on a bus in Eugene.

JH 12 hours of Bad Company! [laughter]

GS But I’m telling you, if you’d have asked us anything about that tape — just hours and hours and hours, Bad Company. Nonstop. You had an 11-hour trip, you listened to Bad Company eleven times.

Fire in the hole!

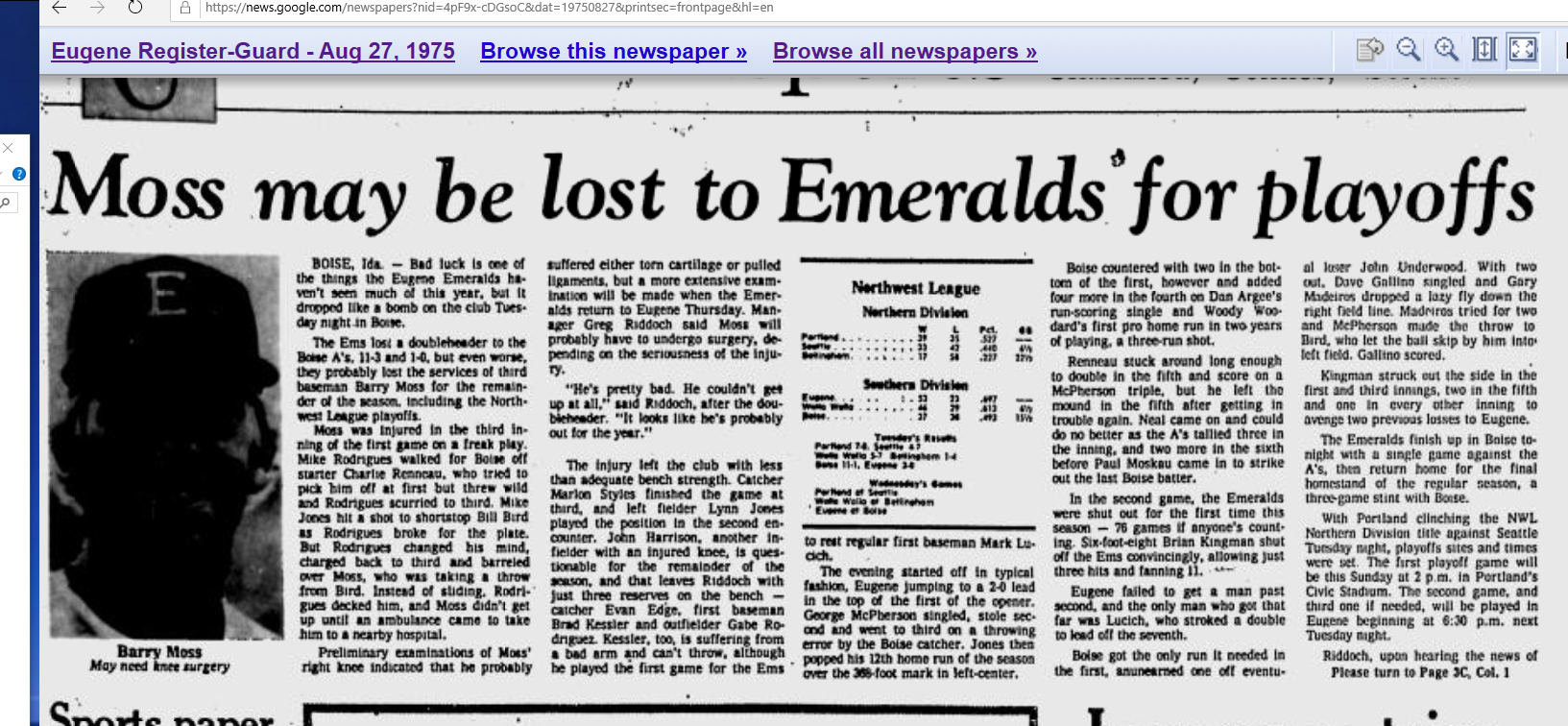

GS So we’re in Boise, Idaho, and we’re playing the Boise A’s. And there’s this kid on the mound. He’s a lefty, and we’re in the first-base dugout. And we are rattling him. We’re rattling the shit out of this kid. We’re talking about his mother. There was nothing off-limits back then.

He’s getting rattled. He’s staring at us. He’s getting really pissed off. We’re just tearing him apart. So there’s a runner on first base. And so he’s got to come to a stop [in his motion, to avoid a balk].

So he comes set. He raises his leg, almost as though he’s going to throw to first. And he basically turns and throws a fastball into our dugout. Everybody hits the deck, and the ball comes screaming in. It hits the back wall and flies back out onto the field. And then it was a mob scene.

JH Imagine that! [laughter]

GS Imagine that he threw a fastball into the dugout!

He got so rattled that he said, okay, I got the ball in my hand. So yeah, I may not throw it to this hitter right now, but you know what, I’m going to try to get somebody in the dugout!

It was crazy. He got thrown out of the game, of course. I think there was a couple of ours got thrown out too, because, you know, then it was just — empty all onto the field.

JH And you don’t want to be caught being the last one out of the dugout, either! That was probably a fine, I bet.

GS Yeah. It was fun and funny back then, but I saw guys lose the opportunity for their careers because of the injuries sustained, because the game was rough. The game was mean, and there were guys that that unfortunately got caught up somehow — got a knee ripped up or an Achilles ripped up, just in a play.

JH Well, two of them I can think of on your team: two of your infield mates, John Harrison and Barry Moss. Barry gets a knee injury in a rundown. And there was a lot of discussion apparently about, was that a cheap shot or not? That knocked him out of the playoffs. And John tore up a leg — a got a big spike wound at second base.

Barry Moss. Barry gets a knee injury in a rundown. And there was a lot of discussion apparently about, was that a cheap shot or not? That knocked him out of the playoffs. And John tore up a leg — a got a big spike wound at second base.

GS Yeah. I was in Billings when that happened.

Quick thinking in Portland

GS So we’re in Portland, and we’re playing on AstroTurf. I’ll never forget it. That was the first time for everybody on AstroTurf. We’d gone to the park early, because you gotta get used to turf. It was amazing how fast — you had to adjust your reflexes.

But that night we played the game, and three of us went to this diner. I don’t even remember who the other two guys were. We’re sitting in a booth, and in walks this old fella, drunker than a hoot owl, and he’s got this really young dame with him, and she’s drunker than a hoot owl. And they’re just laying all over each other and stumbling in and talking loud and laughing. And so we obviously had to notice them. You couldn’t not notice.

So they walked past us, and they had a booth across the aisle from where we were, two or three down. So after a few minutes — I think we probably made some comments about it in the beginning. And the guys facing them might’ve looked over there once or twice.

Anyway, he comes walking over. Well, he comes weaving over. He stands in front of them and he looks over at one of us. And he looks over to the other ones, looks back over, reaches in his damned coat, and pulls out a gun. And he starts like waving it at one side of the table, then the other side.

You think something’s funny?

We’re sitting there, and I’m thinking I’m going to get shot in a diner in Portland — all the way from Tampa — by some old drunk dude with a drunk old woman. This is how this is going to end?

JH That’s not the way you had it in the script?

GS This is not how I thought this was supposed to go.

So he’s waving his gun around and we said, no, what are you talking about?

You laughing at my girlfriend? You laughing at me?

So thought, I gotta get real, real sharp here with him.

I said, no, sir! Matter of fact, we’re all kind of jealous. And he looked at me, squinting, like, what’d you say? I said, yes, sir. I said, you’re the man! He says, I’m the man? I said, you are! You’re the man. Because you got this beautiful young girlfriend. And here we are, three young guys, and all we got is our d— in our hand!

JH [laughs uncontrollably]

GS So he stood there for about 10 seconds processing that.

And I’m thinking, I hope I’m getting to him. I got to blow smoke up his ass.

And he kind of looks and I said, yes, sir. Man, I got to give you all the credit, Pops. I mean, I kind of envy you; I ain’t got no beautiful young thing sitting next to me.

Oh, he says, well, you’re right. She’s a beautiful young thing.

I said, yes, sir. I couldn’t agree with you more.

He says, okay.

He reminded me of Otis, in Mayberry [the town drunk on The Andy Griffith Show].

JH Did he go let himself into his jail cell and sleep it off?

GS He turned around and he walked back and sat down. And that did it. And we got our young, happy, still-alive asses out of there!

JH Oh yeah. Really happy!

GS Let me just — we need to get on down the road!

Mario Soto learns firearm safety

GS Well, Soto — what happened to Mario was, he rented a room with a guy named Marlon Styles.

JH Marlon’s from Cincinnati.

I loved Marlon Styles to death. He brought style and character to the team.

GS I loved Marlon to death. He brought style and character to the team. And Marlon’s name was his moniker. And I mean, true to life: Marlon had more style than all the rest of us put together. Marlon would get dressed up. He was a stylish human being. Absolutely. I mean, he was one stylin’ cat. He really was.

Well, Marlon used to keep a pistol — he’s from Cincinnati, inner city. So one day Mario is in their apartment; Marlon and Mario roomed together. Mario didn’t speak any English. So whatever, however, he finds Marlon’s pistol in the apartment.

You would think he would know how to use it, or maybe he didn’t think it was loaded; I have no idea. But Mario pulls the trigger and he fires the gun into the ceiling of the apartment. And then he ran — but nobody knew where he ran. He thought he was going to be deported!

So that night, for hours, all of us — everybody’s out searching the streets, looking for Mario. But later that night, he came back. So they had to explain to him, he wasn’t going to get deported. But he definitely thought they were going to come get him, put him in cuffs, and take him to the airport.

JH I wonder how the people on the next floor up felt about that!

GS Well, I think they were on the top floor.

JH Well, there’s that! Might be a good thing.

Christine Wren, one of the first female umpires in professional baseball, was a Northwest League rookie in 1975.

GS That was the first year that women ever started umpiring [in the Northwest League].

GS We were as mean and as ugly as you can imagine. We railed at her nonstop. Who was the assistant coach?

JH Pitching coach was Joe Verbanic.

GS He really wore her out.

JH Marlon Styles says that she was actually pretty good behind the plate. Just sometimes she had kind of slow feet getting in position and things.

GS She got beat up.

JH It’s amazing she lasted three years.

GS She got beat up. I know she did with us. I mean, it was nonstop heckling.

JH And she didn’t clear the bench any other times?

GS Not that I recall. She probably wanted to, I imagine. Back then, you could get away with a lot. The threshold was much higher back then.

Smart players and good people: the 1975 Emeralds

JH Another thing that people say about the 1975 Emeralds is that there were so many quality individuals as people on that team.

GS I agree with that. I agree with that.

JH That’s why the bonding has been there. That’s why they’re still having the reunions and doing all these things, is because it was there weren’t egos running wild and it really, really was a true team.

GS And there were a lot of smart guys on that team. I mean, there were a lot of guys who were educated.

JH A lot of college guys, at a time when there weren’t a lot of college guys.

GS Yeah, absolutely. I agree with that statement a hundred percent. I don’t besmirch [today’s] athletes for being superior athletes; I do besmirch them for not having the responsibility of having some class about the way that they act outside of the field, or even on the field.

You’ve been given a privilege. When you are playing for me, and I am compensating you at ridiculous levels, you’re not going to dictate to me what you’re going to do as a member of my ballclub.

JH Just imagine how far that kind of attitude — that’s so prevalent now — that really wouldn’t have flown too well in the Reds organization of the Seventies.

GS Not at all.

The outfielder-turned-shortstop got another surprise when he went from Eugene to Billings midway through the 1975 season – one that paralleled a move made by a member of the Reds’ big-league club a couple of years later.

JH So you played part of the season at Eugene, and then got what I assume you’d consider a promotion to Billings.

GS I don’t know what you’d call it. I just knew they said, you gotta go to Billings and they put me on a flight.

JH Were you replacing somebody, because somebody got hurt or somebody got called up?

GS I don’t recall that. I don’t remember what the purpose was. I didn’t always think about it too much back then. I just — whatever they told me, that’s what I did.

JH Because I see it’s just about a split between Eugene and Billings: 25 games at Eugene (.250) and 20 at Billings. Didn’t hit as well at Billings (.188).

GS I got to Billings, and I was hitting will initially. And then I went into a slump, but because it was only 20 games, you really don’t have a lot of time to get out.

JH You take an oh-for-eight or an oh-for-twelve, and —

GS You’re cooked. You’re cooked in a 20-game season. I started off hitting well, and I was hitting .315 at one time. Then I was hovering around ,300, and then all of a sudden I hit a slump; I couldn’t buy a hit. I don’t even remember where I ended up.

JH .188 for Billings. Nine-for-forty-eight.

GS That sounds about right. And those first nine hits were probably in the first 30 at-bats.

JH That’s how the math works, the way you described your season.

GS And when I got to Billings, they wanted me to play second base.

Sometimes they will move you around, like Ronnie Oester. You know, Ronnie was a  quintessential, prototypical shortstop. He ended up in the big leagues playing second base. He was not a prototypical second-baseman, but it elongated his career.

quintessential, prototypical shortstop. He ended up in the big leagues playing second base. He was not a prototypical second-baseman, but it elongated his career.

JH He was stuck behind Davey [Concepcion], and then Barry Larkin came up. And here was a guy who was a AAA all-star at shortstop. And so that he could play, he really bailed them out after Joe Morgan left the Reds; he gave them 10 years of good second-base play for a guy who was not a second-baseman.

GS No. And he didn’t even seem comfortable at second base. He didn’t look natural at all.

But Hoffy [manager Jim Hoff] comes to me one day, right before the start of the game:

Suke?

Yes, sir.

You’re playing second base today.

I had never played second base in my life. I said, what?

You’re playing second base. Come with me.

So he gets this little Rubbermaid replica of a [second-base] bag, and we go out in right field.

Okay, here’s your footwork: If the ball comes here, you drop back here, you cross here, you do this. Shows me the footwork, right there before the game. Okay, there we go!

JH [laughing] You got that, right?

GS Got it. Got it.

First inning, here we go. There was a guy named Andrew Dyes. This guy’s 6’3”, 230. Looked like a linebacker. First inning, right out of the gate, he gets on first; we got a double-play situation. And as the gods of baseball would have it, they’re going to find out if I can play second base or not pretty quickly.

linebacker. First inning, right out of the gate, he gets on first; we got a double-play situation. And as the gods of baseball would have it, they’re going to find out if I can play second base or not pretty quickly.

Ground ball to the shortstop’s right. So I’m going to get the throw a little bit late in the play. I approached the bag, and in my left ear, all I can hear is him breathing, and these feet, pounding the ground like a Clydesdale. And it’s getting louder and louder. And the shortstop has to double-pump, because the ball gets stuck in his glove. I’m thinking –

JH You’re dead!

GS I’m done. I’m done. This is going to be a broken shin. I’m going to get my legs, my knee, just ripped down – he’s going to get me. I mean, it’s in my ear. I can’t hear anything else in the world, other than this.

Shortstop finally comes up, gives me a throw. Fortunately, he gives me a perfect throw. Left foot on the bag, I hopped across, planted right, turned and threw, and went up. And this freight train comes sliding under me, almost simultaneously. And I dropped to the ground — on my feet, of course – and we get the double play: bang-bang, ump calls him out.

And of course, I dropped off like, yeah, I do this all day. I mean, I know it looked dangerous, but it is a piece of cake. I could do this with my eyes closed. No problem. And at the same time, my nuts are shrunk up like BBs, and my heart’s pounding out of my chest: Get the gurney out here now! Just bring the gurney now.

But it was bang-bang, and it just happened to go off perfectly.

JH A natural!

GS And I was like, yeah, okay. I can do this. I got this.

JH That must have been at Lethbridge. That’s where Dyes played in 1975. Hit .324, too.

GS He was menacing!

The Reds Way

JH Did you have that feeling that you were a part of something different, being in the Reds’ organization then?

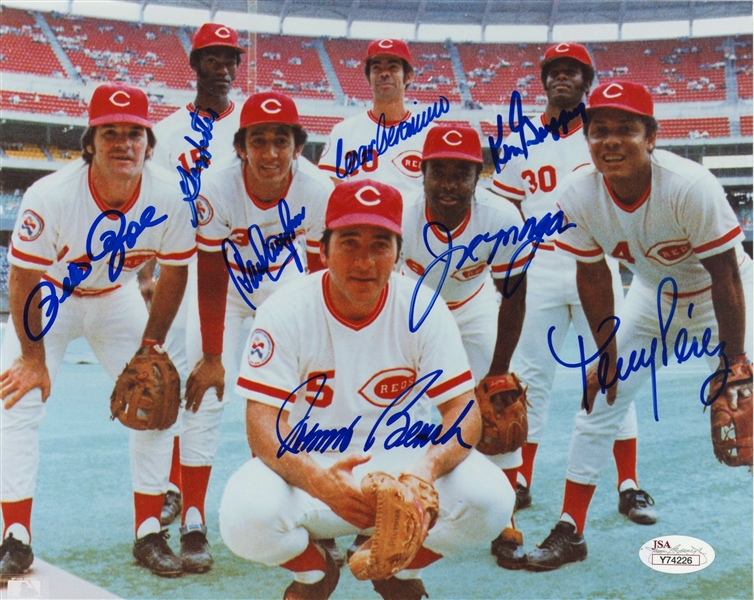

GS Well, I was proud of it. What you’re proud of is the fact that at the time there was The Big  Red Machine. So there’s a trickle-down there automatically. Because here you’ve got a team that is just one for the ages. You’ve got players who are all household names, all over the country. And you are part of that organization, which obviously you felt like, oh, it makes me special too. No question.

Red Machine. So there’s a trickle-down there automatically. Because here you’ve got a team that is just one for the ages. You’ve got players who are all household names, all over the country. And you are part of that organization, which obviously you felt like, oh, it makes me special too. No question.

JH And there was a thing about — even in the minors, the guys had the uniform rules and the pants rules and the socks rules.

GS I hated the socks rules! [Reds players had to wear their stirrup socks low, at a time when many players cut their socks to make the stirrups higher or nonexistent. Not in the Cincinnati organization.]

JH You were a high-cut guy?

GS I just — ugh! [laughter]

And I understand the conservatism. I mean, I do, but — I understand they want to keep everything uniform and keep everything — you didn’t have a bunch of guys like you do now, got all their bling-bling around their neck and all this crap, you know, which I have no appreciation for at all. None. Zero. They didn’t want any of that back then. But I just thought the socks were hideous. [more laughter]

JH I still have a pair of those, by the way!

GS The whole haircut thing was a little bit — you couldn’t have a mustache! I mean, in the Seventies, good God almighty, everything was about a mustache!

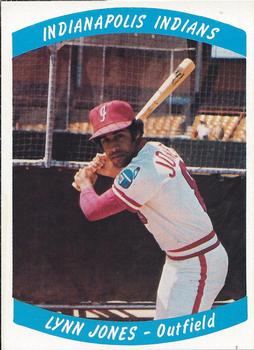

JH Sure! Lynn Jones is the one I think of that way. It looks funny to see him in pictures when he was in the Reds organization, without that big, bushy mustache he had all the time, other places. I mean, it’s like, wait a minute. Who is that? Oh, that’s who that is!

After 1975: Play until they tell you that you can’t

JH So you just got the one season in there, and you split it between Eugene and Billings. What happened after the end of 1975?

GS After that, I played winter ball here in Tampa, where they pulled people from all the different classifications — you had people come in from all over.

JH So was this like a fall instructional-league sort of thing?

GS Yeah.

JH So this is different than Dominican winter ball or whatever.

GS Yeah. This was guys from every level.

What they did was, that winter they signed a bunch of players from the Bahamas and different places. They all came flooding in. And it was somebody’s new idea. I don’t remember whose new idea it was, but there was some debate going on about it at the time. And what it ended up doing was, it put a whole lot of people out there [in the Reds’ system] and it meant a whole lot of people had to go.

And it wasn’t just me. There were some of these guys, they were decent ballplayers, but you’d find one guy that was a decent defensive player who couldn’t hit. Another guy could hit, but he couldn’t do this.

So it precipitated the fact that a lot of people were going; they were going to have to let a lot of people go.

So I got a phone call, and it might’ve been from Plaza: you need to go over to talk to this guy in St. Pete. Here’s his number; give him a call.

And it was a guy with the Cardinals. So I called him and he said, I want you to come over here, do a tryout. I want to work you out one day. So we scheduled a time, I went over there, and there  happened to be another kid there who was from this area who had played with them.

happened to be another kid there who was from this area who had played with them.

And I remember thinking to myself when we were taking ground balls: this guy can’t play with me. He doesn’t have a strong arm. I just didn’t think he had equal tools.

So afterward, the Cardinals guy comes up. He says they want to sign me. And at the time I was all enthralled in a relationship with a girl here. The typical story.

He says, I want to send you to our affiliate in [Tennessee]. And I told him, well, I’d rather stay here and play with the St. Pete Cards because I didn’t want to go anywhere. And he said, well, no. That’s not where I’ve got a spot.

And I said, well, I know I wouldn’t be interested in that. My intention was to sign with St. Pete.

And basically we just didn’t agree. And then that was that.

JH So had you been officially released by the Reds? I mean, Plaza had then recommended you –

GS Go talk to this guy in St. Pete. Yeah.

JH Okay. I’ve heard similar stories from a couple of other guys going both ways. There were Cardinals guys who signed with Cincinnati because everybody was in the same area there. But did they give you a reason for your release?

GS I just went in and we sat down and they said, you know, George, we’re going to — I think they gave me the standard nondescript type of answer. You know, we’re doing some things here. We’re looking at things, some different things, which would have been to all the other players that they brought in. You know, we’re looking at some different directions and there’s just decisions that we have to make. I mean, that’s just a general canned statement.

But I was like, yes, sir. I know. Okay. I understand. I wasn’t going argue or make an ass of myself or anything like that. I mean, there wasn’t any real point in doing that.

But then I went over and I had this trial in St. Pete and the guy wants to sign me up. And I did not want to leave this area at that time. I just didn’t want to go. So I just kinda said, well, it was my intention to play in St. Pete, which was a pretty asinine thing to say at the time. I mean, when they tell you — you want to play, you go [wherever they tell you to go].

So that was that.

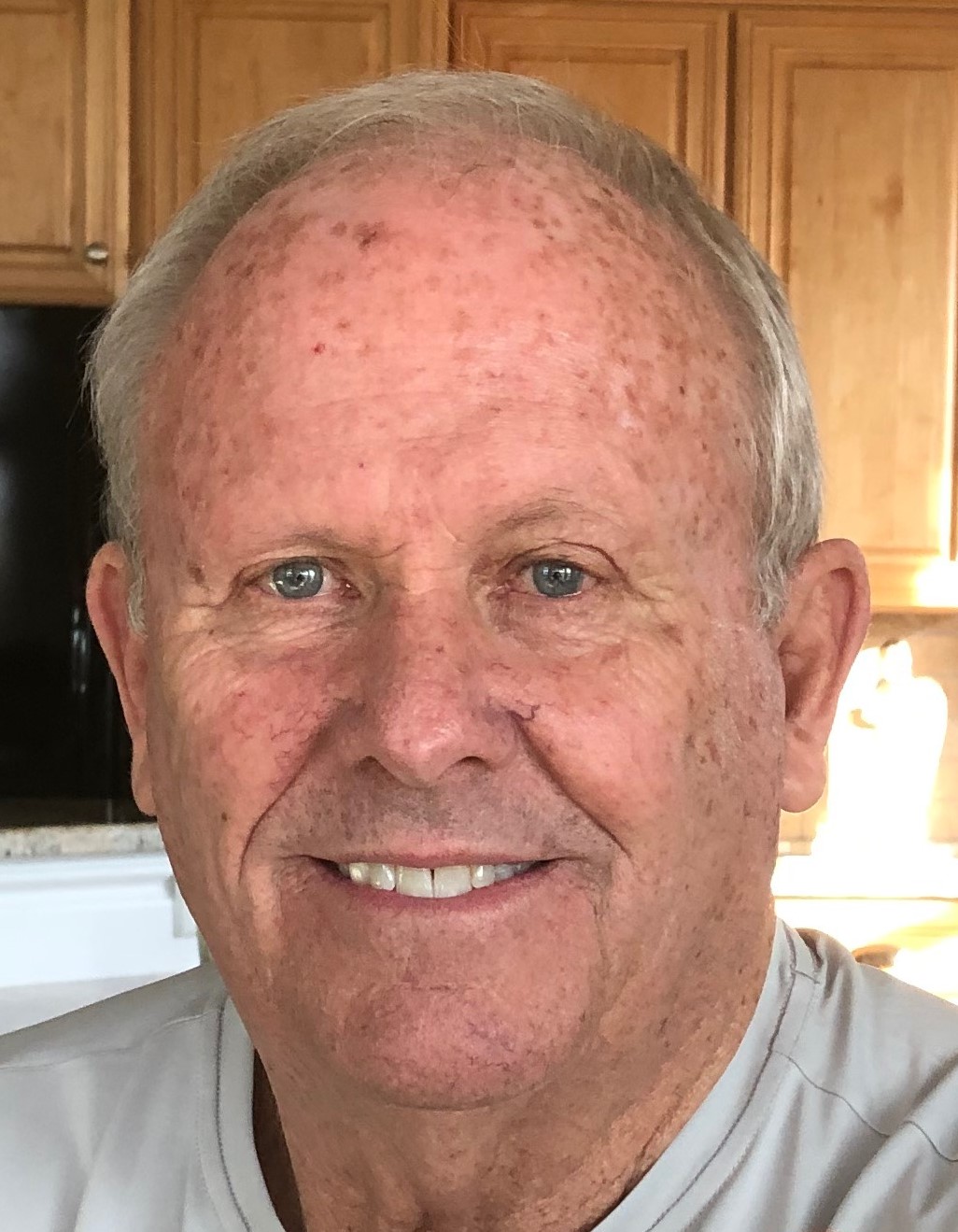

After baseball

GS Two years later, I got into the fire service here, and had a pretty distinguished 35-year career. Retired as a captain and an executive officer, and ended up going to Tallahassee for 23 years, lobbying on behalf of public safety.

I got a real-estate broker’s license; built four houses; sold a lot of real estate; opened a fundraising company. Just had my hands in all kinds of things. Got a gubernatorial appointment by Jeb Bush to work for Florida at one time. So I ended up doing a lot of really interesting things. And I’ve been retired now for eight years.

JH How do you feel about how the baseball ended? I mean, were you still just, okay, it’s time to turn the page? Regrets?

GS At that time, I probably felt relieved. I was tired. I had been playing nonstop; no breaks. I had an interest here, obviously, with a young lady that I wanted to explore and expound on; at least, that was my intention at the time. And all of that was kind of colliding. And so in the end when I couldn’t stay local, I just let it go. I thought that was the right decision to make.

You don’t stop playing baseball until somebody tells you that you can’t play anymore.

Looking back on it, man! I should’ve kept playing, just for the fact that you can keep playing. It’s like I told my son: you don’t stop playing baseball until somebody tells you that you can’t play anymore. That’s the general rule: when somebody tells you you can’t play anymore, that’s when you stop playing.

JH So it was not exactly a heartbreaking decision when you decided to stop, but you did have regrets that you didn’t fully empty the chamber?

GS That is correct. That is correct.

JH You went on and were obviously quite successful after baseball. But when you look back on your playing career, was getting a chance to play pro ball a positive thing, overall, to you?

GS Oh, absolutely! You’re in a small fraternity of people who can say that. I wouldn’t trade that for the world, because I can talk about what it’s like to be a pro athlete. The discipline, the training — you’ve got to have the physicality of being a pro athlete. I think it’s different now. You know, we did not have all the supplementation that these guys have; it was a different time. That’s why you see athletes now, they’re all bigger. They’re all faster. They’re all stronger, as a whole, than would have been [the case] in 1975. You know, there’s reasons for that. But I would never have changed that opportunity for anything in the world.

It was wonderful. I met a bunch of people. I got to travel around. I got to play a lot of baseball. It teaches you — you learn a lot. And I enjoyed every bit of it. Absolutely. Because there’s not a lot of people who can say that.

When I was coaching youth baseball and AAU, when my son was coming up, the minute you would tell parents, I played a little in college, and then I got signed by the Cincinnati Reds and I played pro ball you had instant credibility.

JH So that raised your game in the parents’ eyes, especially.

GS Absolutely did! Because my son was a really good baseball player. And so he played AAU, and he played on teams that were an extremely talented bunch of kids. They were playing at a level a couple of steps above the average kid. And so having dads around, you weren’t “just another Dad.” Well, he played pro ball, so right away, others are curious to know what you know; they want to find out what you can teach, and how you teach it — because they’re going to put it in their repertoire.

One of George’s biggest challenges as a coach was to make parents understand that there comes a point where all the extra work in the world cannot overcome talent for the game.

GS You know, I had a guy one time — his kid was always the biggest kid on the field. He was 12 years old. He was six feet tall, 200 pounds, and the kid had talent. And he was this nice, easygoing — I call him almost sort of a mush.

His father had been a basketball player, and he was good. But he didn’t know diddly about baseball. He knew nothing. So he was learning while his son was playing. He and I became fairly good friends, because he and my son played on a number of teams together.

And I’ll never forget: One day we got into this debate. His position was, if you hit a kid a thousand ground balls a day, you throw him a thousand pitches of BP a day, and you do this day in and day out, one day your kid will be Derek Jeter if he’s got any talent. And I told him, nope, doesn’t work that way. We argued this for two years.

I would tell him, there’s levels of talent. There’s levels [of play] that are attainable, based on that talent. And I don’t care how many ground balls you hit at a kid; I don’t care if he loses every tooth in his mouth, it doesn’t mean he’s going to be Derek Jeter.

Two years we argued about it!

But one day I used this ridiculous, stupid, silly analogy — but it worked:

I said, Ken, I’m a sculptor. You come to me one day with a block of clay: George, I want you to sculpt this vase for me. Here are the specifications. Here’s how I want it the finished product to look.

Okay, Ken, I’ll get to work on it.

I work on this vase for months and months. One day Ken comes back to me. And I explained to him I cannot create the vase that you want, with the specifications that you gave and the shape of the finished product.

And he says, why?

And I said, simply: you didn’t give me enough clay.

I said, Ken, clay is talent.

And for some reason that turned on the light.

Some kids have got enough talent — notwithstanding a thousand ground balls, or a thousand pitches in BP — they’ve got enough talent to reach the high-school level. If they reach their optimum ability, based on their talent, they get as good as they can get. They can’t get any better. They might play high-school baseball. Some kids might play college baseball; maybe they’re borderline drafted.

And then there are those guys like Derek Jeter, who is simply Derek Jeter. That’s why he’s in the big leagues. Not that he did or didn’t take a thousand ground balls, or take a thousand pitches a day. The fact of the matter remains, he had enough talent to get to the big leagues.

His talent level — his clay — was greater than the kid who could only play high-school.

And Ken finally admitted to me that makes sense. Well, God help us all! Two years it took me to get this through his head.

JH I mean, there’s, there’s a ton of painters, but there’s only one guy who did the Sistine Chapel.

GS Thank you very much!

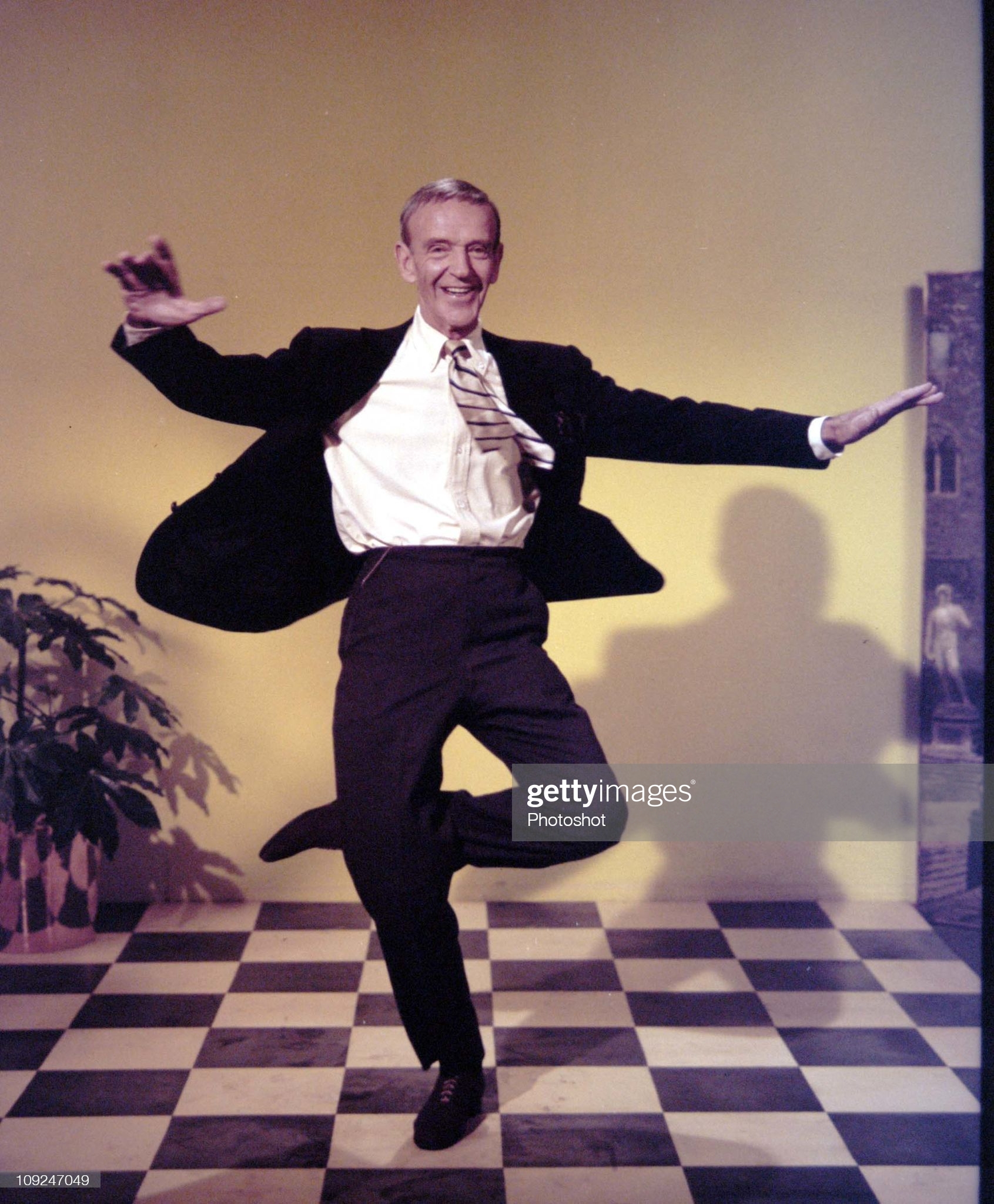

Professionals make things that are very difficult to do, look easy. I tell people: just watch Fred Astaire. He doesn’t even look like he’s breathing hard. It looks like he’s taking a walk when he’s doing some extremely difficult, physically demanding moves. And he does it with such elegance  and such grace!

and such grace!

And then you go try to do that. You think, oh my God, I don’t look like that. I can’t. And that’s what pros are: people who take something that’s very difficult to do and make it look easy.

George got a lesson in that at Reds spring training:

I remember being at spring training right in the outfield, right behind shortstop, and Davey Concepcion was taking fungos. And they’re hitting him some shots and he almost looks like he’s  in slow motion, because his movements were always so fluid, so graceful. And you’d find him in position to take care of the ball and not look like he was putting a whole lot of effort in it.

in slow motion, because his movements were always so fluid, so graceful. And you’d find him in position to take care of the ball and not look like he was putting a whole lot of effort in it.

He slowed down the baseball.

JH Do you think it’s the same for a fielder as it is for a hitter? When you’re not hitting, and you’re up at the plate, the ball looks faster. It looks smaller. It looks dirtier. And it looks like there’s 30 guys out there in the infield, and you’re never going to hit through them. But when you are hitting, the ball looks bigger, whiter, slower. Maybe it’s the same for fielders. Did you feel that way?

GS Sometimes; there were days where — and I don’t know if it’s an internal thing; I don’t know if it’s a spatial thing — but there were days where you just didn’t see the ball the same. Your timing was off. Your timing approaching the ball, the timing in your head, watching the ball bounce — all of a sudden you were discombobulated. Like you were trying to walk when you were a little bit dizzy, your equilibrium was slightly off, or something. That’s how it felt. It just didn’t feel natural.

JH What do you think makes good hands for an infielder? Is that a gift? Can that be developed, or how do you feel about good hands — soft hands?

GS I think you’ve got to have an instinct, first and foremost. You got to see a baseball come off a bat and have an immediate reaction where you think that ball’s going. And I’ll tell you, as silly as this might sound:

You got these baseball video games, and a guy gets up and hits the ball, and where the ball’s  going, they put a circle. And you gotta make your player run to the circle. In the real world, a guy that’s really, really good, the minute the ball comes off the bat, the trajectory, the sound, the speed, he reads that within microseconds and he takes off for a spot. And that’s why you see some of these guys make plays that I consider to be great plays, because if they don’t get that jump — if they don’t react and they don’t go to that spot where they think that ball that’s going to travel — they gotta be right there on that dot where that ball is going to drop.

going, they put a circle. And you gotta make your player run to the circle. In the real world, a guy that’s really, really good, the minute the ball comes off the bat, the trajectory, the sound, the speed, he reads that within microseconds and he takes off for a spot. And that’s why you see some of these guys make plays that I consider to be great plays, because if they don’t get that jump — if they don’t react and they don’t go to that spot where they think that ball that’s going to travel — they gotta be right there on that dot where that ball is going to drop.

I don’t think you can teach that.

JH How long were you a scout?

GS Probably for about three years, but my son had gotten to the point where — I wanted to be out there with my son playing baseball. I didn’t want to be traveling around the local areas, scouting kids. And I had my hands in different things; it wasn’t like I was doing one thing, and I’m gonna get bored with it.

JH But you still must have had baseball in the back of your mind somewhere.

GS Of course!

JH I guess you get hooked on baseball, and it’s there for life.

GS Yeah! I feel blessed every day.