Dave, you are widely known as the ultimate baseball guy. How do you explain your lifelong love of the game?

Some people like chocolate, and some like vanilla. I just loved it from the day I got my first glove.

But you were quite the football player, too – with a scholarship offer to Georgia Tech.

Football was a means to a college education.

But you eventually turned that down to play baseball.

I promised my mother when I signed to play baseball that I would finish college. Took me eight years, but I did. I’m proud of that, too.

From player to manager

You were a career .280 hitter at second base in the minors, but after five seasons, you were made a player-manager. Did the organization tell you that your future was in managing?

They just said, ‘you’re going to Hornell, New York to take over a ballclub.’

As quickly as that? The 1957 season had already started.

I was in Wausau, Wisconsin, of all places, and the Reds had sent some players to Bradford, Pennsylvania and the team folded after they were 5-15. They called the Reds’ office: what do they want us to do with these extra players that belong to Cincinnati? ‘Tell them to go to Batavia, New York, and we will have a manager and some more players there in two days.’

When I got to Hornell, we had three pitchers. They all pitched in the first three games, and we won all three.

On the fourth day, a guy waked into the office at noon and told the GM, ‘I’m a pitcher. Can I get a job?’ We signed him, and he pitched that night [laughs].

I managed my first game against Olean, New York, and Paul Owens was the player-manager for Olean. He later hired me to coach at Philadelphia.

You were a player-manager for several seasons. What ended your playing career?

Well, along came Tommy Harper, and along came Pete Rose.

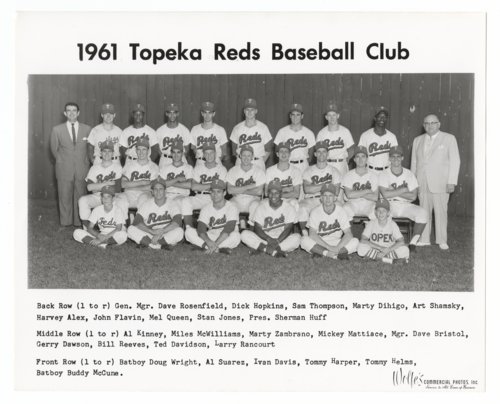

In 1962, Cesar Tovar was the MVP of the NYP League; Pete Rose was MVP of the Florida State League; Tommy Harper was MVP for Topeka of the III league. All three were second-basemen.

The Reds produced some good players; that’s why I was lucky to be able to manage a lot of them. They could play! And they loved to play!

But that was my job – to manage — and I loved it.

Was it a difficult adjustment to give up playing? You were still in your 20s then.

I saw that I wasn’t going to make it as a player, so you have to change over and aim higher. I wanted to get to the big leagues. If you don’t aim at something, you’ll hit it every time.

It worked out good. I managed D, C, B, A, AA, AAA, Instructional League, winter ball, and the big leagues.

A “fundamental maniac”

And throughout your managerial career, you stressed fundamentals. Darrel Chaney told me you were a “fundamental maniac” and drilled that into the players every day.

The Reds were great. Our farm system had people who believed in that. We didn’t have  to take a back seat to any organization about teaching fundamentals.

to take a back seat to any organization about teaching fundamentals.

It’ll haunt you if you don’t have good fundamentals – how to play the game. Chaney was a recipient of a lot of that coaching – with two different teams! [laughs]

You have 27 outs. Don’t waste ’em!

Bobby Mattick was a Reds scout who signed a lot of good players. He used to say, ‘I’ll sign them. You send them to Bristol, and he’ll work on them.’

Developing as a manager

How much of your managerial style did you have to develop on the fly, starting the way you did?

I was young: 22-23. Everybody in the Reds organization tried to give me help.

I would copy anybody if I thought it would help me. And we had some scouts who would really help me.

When I managed in Hornell and Geneva, Dutch Dotterer was the area scout for the Reds. He lived in Syracuse, and he loved baseball. He would come early and spend the day; he was good for me.

And a lot of old-time scouts helped. One from the Phillies once told me: ‘Dave, if you leave the dugout to take the pitcher out, bring him back with you. Don’t let him talk you out of it.’ I’ve always remembered that.

Dutch Ruether, a left-handed pitcher who played for the 1919 Reds, was a Giants scout when I managed San Diego. I learned a lot from him, too.

Are there things you wish you could have done differently as you grew as a manager?

I wish I knew as much about pitching then as I do now.

I had a pitcher in Palatka who pitched two no-hitters, two one-hitters, and two two-hitters. Now, that’s pretty good. He made it as far as AAA. He might walk 13 and strike out 14. It would drive you crazy — but hey, that’s part of it.

I had Ken Hunt in Visalia, and he was wild and everything. I said ‘you’re going to pitch nine innings one way or another.’ He got to 4-2/3 innings and I brought in a relief pitcher to get the third out, put Hunt in the outfield, and brought him back to the mound. He finished the game. The next year he pitched great at Columbia.

In the first half of the 1961 season, he was something like 9-1 for the Reds. The second half of the season wasn’t much for him.

In 1962, the Reds sent him to me at Macon, Georgia, and he was wild again. He was pitching one night, and in about the third inning, he wound up and threw the ball over the top of the grandstand by the press box. He walked off the mound, and I’ve never seen him since.

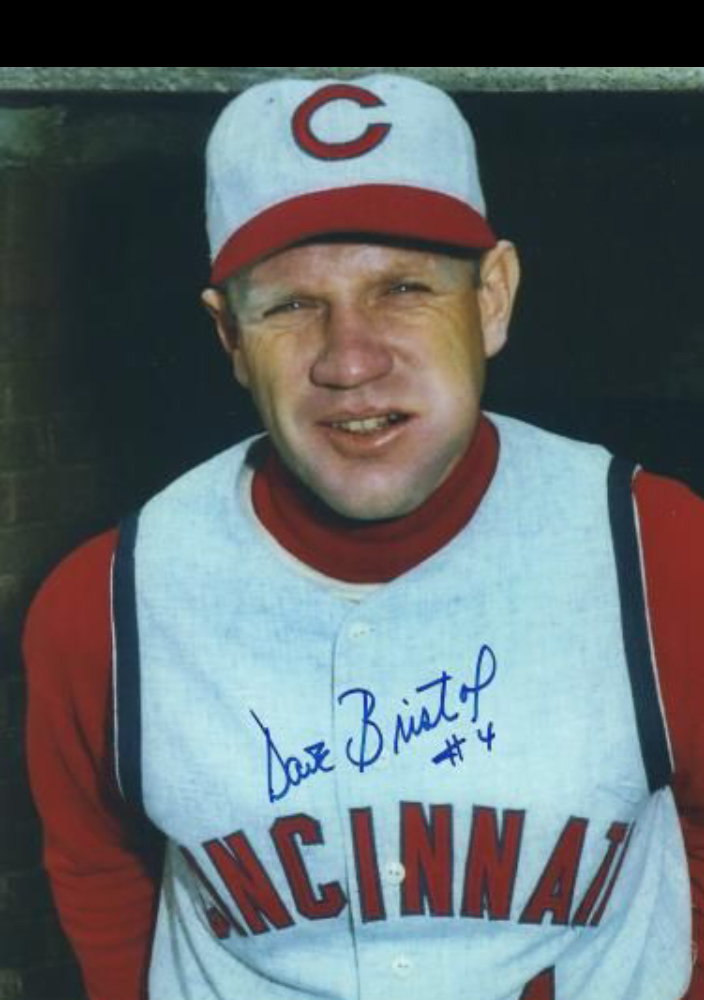

1966: In the big leagues with Cincinnati

You just missed a chance to manage Frank Robinson with the Reds.

The best manager I ever played for was Earl Brucker, who was a coach for Connie Mack for many years. In 1953 he was our manager at Ogden, Utah — Ken Hunt’s home town. And we won the pennant.

Bobby Mattick brought Frank Robinson in there — 17 years old, after graduating from McClymonds High School in Oakland. He played 70 games and drove in 72 runs. What a player!

And if they would have asked me about trading him, I would have said ‘no.’ He could win the game for you—shoot! — Dave Bristol, on Frank Robinson

[The Reds traded the 30-year-old Robinson to Baltimore after the 1965 season; he won the Triple Crown for the Orioles in 1966, when Bristol was named Reds manager in midseason.]

What if they would have kept Robinson? We traded him, and lost Claude Osteen and Jimmy Wynn. Imagine Wynn hitting in Crosley Field! I think we might have found a place for him!

You took over the Reds in midseason 1966, when Don Heffner was fired. You had winning records each year, yet you were fired after the 1969 season. How did that  come about?

come about?

Bill DeWitt hired me, and then he sold the club [in 1966]. After it was sold, they brought in Bob Howsam from St. Louis as general manager.

It’s been reported that you and Howsam did not see eye-to-eye, and that was a factor in you being let go.

I got along great with Bob Howsam. He knew how to run a ballclub, and he gave me a two-year contract. I never had a cross word with him. He told me I was coming back the last two weeks of the [1969] season. I was surprised, really. But hey, things happen.

But hey, Sparky Anderson came in, and did a hell of a job. And he did a hell of a job in Detroit. And he had good talent at both places.

[It should be noted that despite having just been fired by the Reds, Dave met with Sparky Anderson during the 1969 World Series, to give Sparky a full rundown on the Reds players so he could hit the ground running with Cincinnati.]

But who developed that talent for him in Cincinnati?

Hey, it’s more than me. How about the scouts who signed them?

The Big Red Machine is yours, as much as it is anyone’s.

That’s kind of you to say. I’m proud of them!

After the Reds

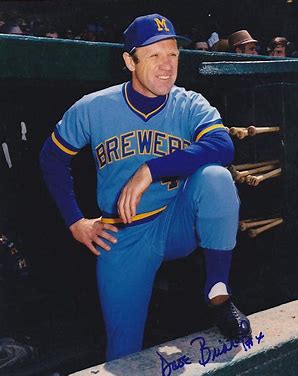

You moved on to the Seattle/Milwaukee franchise in 1970. What was that experience like, compared to Cincinnati?

That was a big culture shock, going from the Reds to the Brewers. It was basically an expansion team – it was their second year. The caliber of players just astounded me.

expansion team – it was their second year. The caliber of players just astounded me.

Look [by comparison] at the Reds team – that was some good players! History has proven that.

We had a good coaching staff in Milwaukee, and we worked hard to be the best that we could.

Wes Stock was a heck of a pitching coach. Jackie Moore was bullpen coach. Cal Ermer had managed the Twins, and was third-base coach. Roy McMillan was infield coach. Good coaches and good people!

But the caliber of players just wasn’t the same [as Cincinnati].

Things didn’t work out in Milwaukee, and early in your third season there, you were fired.

The general manager who hired me got fired. Bud Selig brought in Frank Lane, and he didn’t like me and I didn’t like him. He would trade players without even asking.

Is it tough to be successful when you and the GM don’t see eye-to-eye?

That’s for sure. He wanted me out of there.

After my second year in Milwaukee, Gabe Paul got permission to talk to me about coming to Cleveland. I said no, I will honor my contract. I’m not made that way [to jump contracts]. I’m not going to do it.

Gabe said, ‘I’ll bet you a new hat that Frank Lane will fire you by the end of May.’

On May 20, I sent Gabe Paul a new hat.

So Lane was laying in the weeds for you?

No question. He didn’t want me from the time he was there. At the press conference, he said, ‘I don’t know how we will get along without you, but in the morning we’re going to start trying.’

You had a great line about being let go by the Brewers in 1972.

I said, ‘It was a neat incision. There will be no scars, and the patient will be up within two days.’ And I told the traveling secretary to get me a one-way plane ticket to Chattanooga.

I sent Bud Selig a picture of the two of us on the dugout steps, Opening Day in Milwaukee. I wrote on it, ‘This was probably the only time we smiled all year.’ I was hoping he would sign it and say something, but he didn’t. I was disappointed in that.

Of course, he’s probably disappointed in me, too.

But I gave them all I had, I’ll tell you that. Hey, move on and look for something else.

You didn’t have to look very long; you were with the Expos in 1973.

Manager Gene Mauch said, ‘you got a job, so don’t worry’ and I went to Montreal for three years. After Mauch got fired, I went to Atlanta in 1976.

Your time in Atlanta was best known for Ted Turner sending you on “vacation” in the middle of the 1977 season, and managing the team himself for one game. How did you deal with that?

did you deal with that?

I said, ‘the commissioner won’t let you do that.’ He got by for one game, then called me and said ‘I will see you tomorrow night at the ballpark’ like nothing had happened. And that was kind of embarrassing, you know.

It worked good when he turned it over to John Schierholz and Bobby Cox, and got out of the ballpark. It worked out great for 14 straight years; that was wonderful.

And then you coached and managed in San Francisco in 1979 and 1980.

We had pretty good players, but here again, Spec Richardson, the GM, loved me.

One of the hardest things I had to do was tell Willie McCovey that his playing days were

over. That was tough. You couldn’t ask for a better guy than Willie McCovey — Dave Bristol

You had to do the same thing in Cincinnati, with pitcher Joe Nuxhall in 1967.

It was the same as telling Nuxhall. I told him, ‘hey, they’re going to make you the second guy on the radio; it might work out good.’ Hell, it worked out 40 years good. He’s an icon now.

I loved Joe Nuxhall. The salt of the earth. We were dear friends.

2018: The Reds Hall of Fame

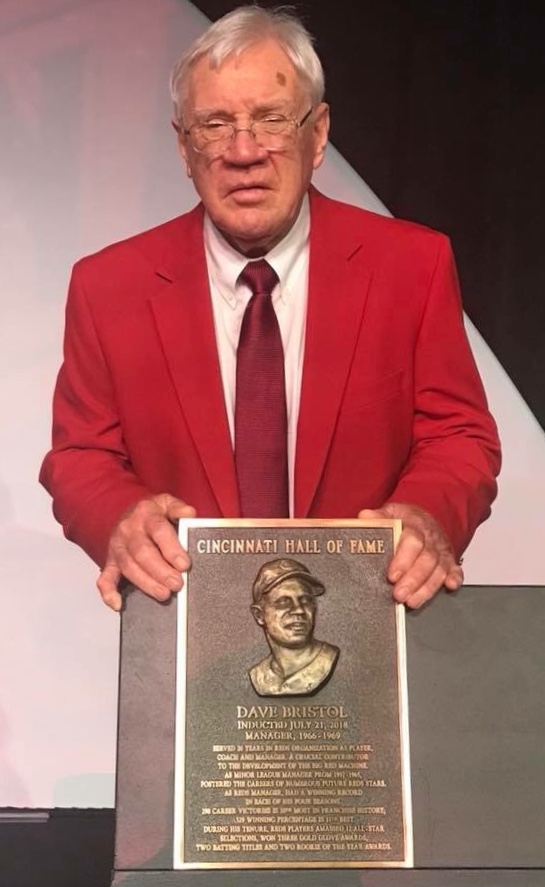

And now you have finally received some long-overdue recognition, with your election to the Reds Hall of Fame. Was Induction Weekend what you had hoped it would be?

And more. That was outstanding! And no one had a better time, and no one will wear  that red jacket with more pride than I will.

that red jacket with more pride than I will.

Your former players seemed to be as happy as you were.

Wasn’t that wonderful? Tony Pérez and Johnny Bench and Tommy Helms had the nicest things to say. George Culver came all the way from Bakersfield, on his own, to see me. I was tickled to death!

You’re still active, coaching young players. At age 85, do you still have energy and passion for the game?

Still do! I love it. I get a kick out of it today. I go to minor-league baseball games, and I talk baseball every day.

I’m still trying to impart some wisdom to those kids.

Some people like chocolate, and some like vanilla. I just loved it from the day I got my first glove. — Dave Bristol, about his love for the game

You have given your life to the game. How would you like for Dave Bristol to be remembered?

‘He competed, and he wanted his players to play the right way and be good citizens.’ That means a lot to me.

I released an infielder in Palatka, Florida, in 1960. He didn’t like it. He went to New York City and became very big in the Postal Department. Later, he told me, ‘I didn’t like it at the time, but the things you stressed and taught me have helped me become a better person, and made me a lot of money.’

You gotta love that!